What is it like to die? In 2012, the retired US neurosurgeon Eben Alexander reassured us in his book Proof Of Heaven that it is a blissful experience. Of course, he wasn’t speaking from beyond the grave. His claims were based on what he said had happened to him during a week-long coma a few years earlier.

While close to death and with his E. coli-infected brain rendered virtually inactive, Alexander said he had a transformative experience that included travelling through a black void “brimming over with light: a light that seemed to come from a brilliant orb”.

He also described being comforted on his journey by a young woman with high cheekbones and blue eyes, who told him he had nothing to fear and that he was “loved and cherished, dearly, forever”.

Alexander’s fantastical account divided opinion. Millions rushed to buy his book, and the US magazine Newsweek splashed his story on their cover with the headline “Heaven is real”. Yet eminent neuroscientists such as Sam Harris and Colin Blakemore queued up to pick holes in the account and to present a more biologically grounded version of events.

Read more about death:

- Death redefined: how pig brain function was restored after slaughter

- The Immortalists: Can science defeat death?

“Of course, the brain does funny things when it’s running out of oxygen,” wrote Blakemore at the time. “The odd perceptions are just the consequences of confused activity in the temporal lobes.”

Alexander’s story contains several features of what researchers today call a ‘near-death experience’ (NDE).

The term was coined by the US psychologist and philosopher Raymond Moody in his 1976 bestselling book Life After Life in which he presented the accounts of 150 people who’d come close to death, noting that they often contained the same features, such as: a bright light; an out-of-body experience; the comforting presence of other people; feelings of wellbeing and reduced fear.

It’s possible to trace similar depictions further back in time, however. For instance, Ascent Of The Blessed, painted by Hieronymus Bosch early in the 16th Century, features a bright light at the end of a tunnel.

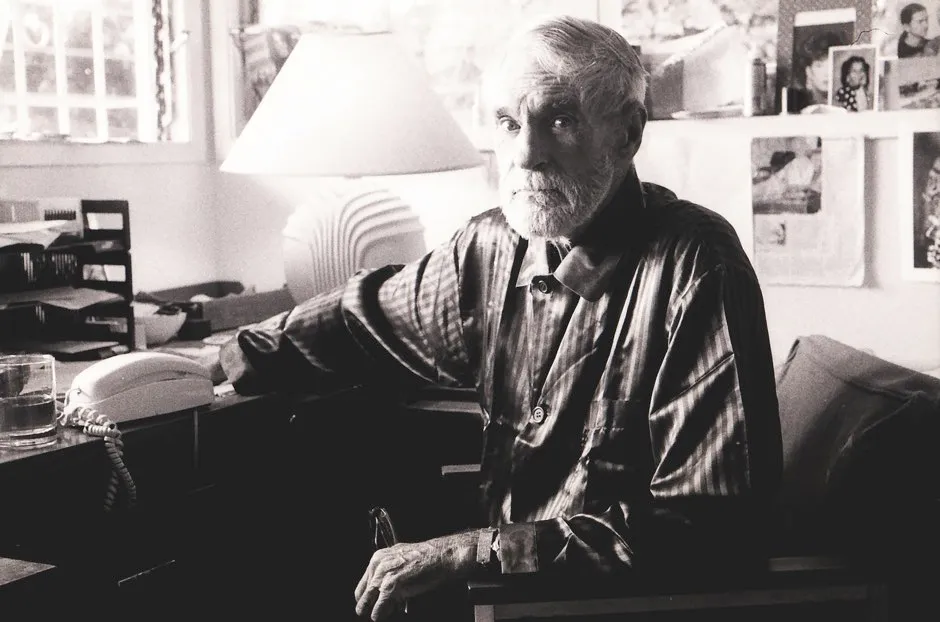

Just as Alexander’s story split opinion, so too have NDEs more generally. Some scientists, such as Dr Bruce Greyson, professor emeritus of psychiatry and neurobehavioural sciences at the University of Virginia and co-author of The Handbook Of Near-Death Experiences, believe that they challenge a purely physical account of human experience. NDEs “…present us with data that are difficult to explain by current physiological or psychological models,” he wrote in 2013.

However, many others, such as Dr Charlotte Martial at the Coma Science Group at the University Hospital of Liege, and Chris Timmermann at the Imperial College Psychedelic Research Group, believe there is a scientific, neurochemical explanation for NDEs.

Martial says she is “very convinced” by such explanations, though Timmermann cautions that “definite proof might be impossible with our current tools, because it would require for researchers to probe in the brains of human beings at the moment of death, which is unethical.”

Drugs and near-death

The neurochemical account is given weight by a curious observation. Many of the key features of an NDE are recounted not only by people who have nearly died, but also by people who have taken psychedelic drugs.

These include, but are not restricted to, psychedelics that act on the serotonergic system in the brain (serotonin is a neurotransmitter that’s involved in mood and perception, among other functions).

Such drugs are known as the ‘classic psychedelics’, and include LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), psilocybin (the hallucinogenic compound in magic mushrooms) and DMT (dimethyltryptamine or ‘spirit molecule’, which is found in several plants located in the Amazon basin).

Psychedelic compounds have been used throughout history for spiritual adventure or to visit the afterlife. In the 16th Century, the Spanish Franciscan friar and missionary Bernardino de Sahagún described the use of mushrooms by indigenous people in Mexico leading them to experience “terrifying and amusing visions” and how “some saw themselves dying in a vision and wept”.

Further south, in traditional ayahuasca ceremonies in the Amazon rainforest, shamans still use a brew made out of DMT-containing Banisteriopsis caapi vine (they call it the ‘vine of the dead’) to contact spirits.

In traditional cultures in central Africa, meanwhile, the psychedelic shrub iboga is used to induce an NDE as part of initiation ceremonies designed to broaden young people’s minds.

Indeed, the parallels between psychedelic trips and NDEs have been observed for decades. It’s notable that the second LSD trip ever experienced by a human featured classic NDE elements, as recorded first-hand by the discoverer of the compound, the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann on 19 April 1943.

Read more about drugs:

- Sleep, drugs and mental health: how altered states of consciousness could keep us happy

- Small doses of psychedelics might help you solve problems

“My body seemed to be without sensation, lifeless, strange. Was I dying? Was this the transition? At times I believed myself to be outside my body, and then perceived clearly, as an outside observer, the complete tragedy of my situation,” Hofmann wrote in his book LSD, My Problem Child.

Elsewhere, the controversial former Harvard psychologist and psychedelic evangelist Timothy Leary even likened to trips to “experiments in voluntary death”. Yet it is only very recently that scientists have begun to make a formal comparison, opening the possibility of using psychedelics to model the experience of near-death.

“One can hypothesise that some endogenous molecules [ones that are generated by the human body] mimicking DMT or ketamine mechanisms could be released in life-threatening situations, when an individual experiences an NDE,” says Martial.

Delving deeper

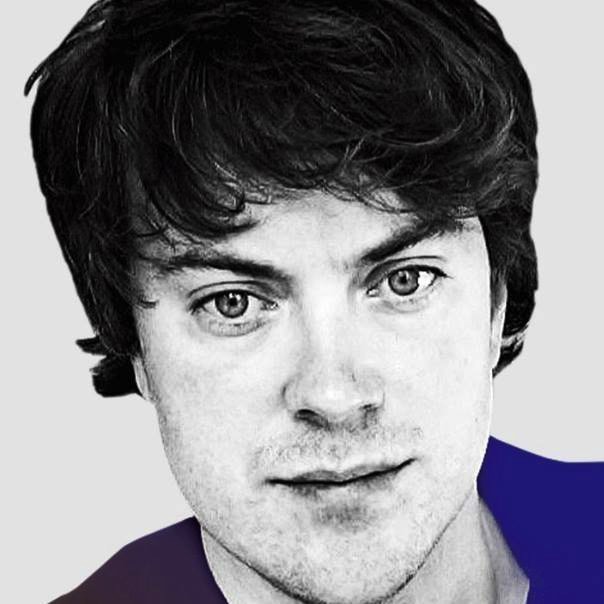

In 2018 an international team led by Timmermann and Robin Carhart-Harris at Imperial College, and including Martial in Belgium, conducted a small trial in which they asked 13 volunteers to complete a well-established measure of near-death experiences, both after taking DMT and after taking a placebo pill (for example, they rated how much they felt separated from their body, how much they had a sense of peace, and whether they saw a bright light).

The researchers also compared their volunteers’ experience under the influence of DMT with the reports of 13 people who’d had a ‘real’ NDE after a life-threatening episode. They found that, after taking DMT, all 13 of their volunteers had effectively had an NDE based on their scores on the formal near-death questionnaire.

The team also observed “few discernible differences” between the actual NDE cases and those induced by DMT. In a study published in March 2019, Martial led another international research group who took a different approach to the same question.

They compared the similarity of the first-person descriptions of approximately 15,000 psychedelic trips with the retrospective first-person accounts of several hundred near-death experiences collected in Belgium and the USA.

The similarities between the two kinds of experience were striking, with the NDE-like nature of the trips being especially apparent for people who’d taken one of the classic psychedelics, and most of all for people who’d taken ketamine – a so-called ‘dissociative psychedelic’ that is used in medicine as an anaesthetic.

“In short, researchers now have indirect and more direct empirical evidence of certain neurophysiological mechanisms underlying NDEs,” says Martial.

Defining death

There are also similarities in the long-term effects of NDEs and many psychedelic trips. In both cases, people who have been through the experiences describe them as feeling ‘realer than real’, highly memorable and personally transformative. For example, a 2019 study involving dozens of people who’d had an NDE found that more than half considered it a self-defining memory.

Similarly, psychedelic experiences have been shown to have lasting effects on personality, with people frequently describing their trip as one of, if not the most personally meaningful and spiritual events of their lives.

Martial and other researchers believe that the reason that many psychedelic trips are subjectively and psychologically so similar to NDEs is that, close to death, the brain releases chemicals that are the same as, or act in a similar way to, psychedelic compounds.

Supporting this neurochemical account, DMT is known to be present in the brains of humans and other mammals, and a study published in the summer of 2019 even found that concentrations of DMT increased after cardiac arrest was induced in rats – perhaps as a function of its neuroprotective properties. Other scholars have made a proposal that a ketamine-like substance with a similar protective function might be released close to death.

There are also similarities in the level of changes seen in brain activity observed after cardiac arrest and following ingestion of psychedelics – in both cases, activity becomes more synchronised across the entire brain. It is speculated that this might be responsible for feelings of oneness with the world, also known as ‘ego dissolution’ (see box, below).

How do psychedelics affect the brain?

‘Classic psychedelics’ like LSD and psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms) are chemically similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin produced by the brain. Serotonin is involved in many neural functions including mood and perception. By mimicking this chemical’s effects, the drugs exert their profound effects on subjective experience.

DMT (or dimethyltryptamine) too acts via serotonergic pathways (the system involving serotonin), but also through other routes – for instance, DMT binds with sigma-1 receptors that are involved in the communication between neurons.

Meanwhile, ketamine – among many other effects – blocks NMDA receptors that are involved in the functioning of the neurotransmitter glutamate.

A key brain area for psychedelic drugs’ effects appears to be the temporal lobe, the location of much emotional and memory functioning. For instance, removal of the front part of the temporal lobe (as a radical treatment for epilepsy) has been shown to prevent the psychological effects of taking LSD.

Interestingly, abnormal activity in the temporal lobe, such as during seizures, can lead to events similar to near death experiences.

An effect shared by different psychedelic substances is that they increase the amount of disorganised activity across the brain – a state that neuroscientists describe as being ‘higher in entropy’.

One consequence of this is a reduction in the activation of a group of brain structures known collectively as the ‘default mode network’, which is associated with self-conscious and self-focused thought.

One theory, then, is that psychedelics provoke a spiritual state of oneness with the world by increasing the brain’s entropy and suppressing the ego-sustaining activity of the default mode network.

Read more:

Not everyone is entirely convinced by the current proposed neurochemical explanations. For instance, the US pharmacologist and international psychedelics expert Prof David Nichols wrote a paper in 2018 in which he argued that the concentrations of DMT in the brain are too minute to be responsible for the psychoactive effects observed during NDEs. However, he says that “as a scientist, I do believe there is a neurochemical explanation for an NDE.”

Timmermann, who led the aforementioned 2018 comparison of DMT trips and NDEs, hears Nichols’s concerns but still believes that endogenous DMT may play a role in NDEs, possibly alongside other neurochemicals. And even if it turns out that chemicals such as DMT or ketamine are not involved in NDEs, he argues that psychedelics provide a useful model for studying the psychological experience of dying.

“…[T]he experience of death is something which we are only beginning to become interested in from a scientific perspective, and thus models which can be safely used in controlled environments will be valuable for us to understand what these experiences are about and also why they might have such a strong impact on people’s lives,” he says.

Listen to palliative medicine expert Dr Kathryn Mannix talk about the experience of death on theScience Focus Podcast:

The experience of death is still largely unchartered territory for science, and for obvious reasons (Martial and her colleagues noted wryly in their 2019 paper that “…dying is difficult to study under controlled laboratory conditions by means of repeated measurement”).

Even if NDEs provide a window into the experience – and psychedelics can be used to model and investigate the same or similar processes – it’s notable that the majority of people who are resuscitated after being close to death do not report NDE-type memories of what happened.

“Since no one has actually died and come back to tell about it – I mean a death that is not reversed – we can’t know whether DMT or ketamine are good models,” says Nichols bluntly. “They may model the NDE, but we don’t know whether an NDE is actually similar to the experience of dying.”

On a positive note, the profound, NDE-like nature of many psychedelic trips has opened new avenues for helping alleviate existential suffering for people with terminal illnesses. Just as many people who emerge from classic NDEs subsequently report a dramatic loss of fear for the afterlife, so too do individuals who have enrolled in trials for psychedelic-assisted therapy for existential anxiety.

Research groups around the world are now exploring these therapeutic possibilities, including at New York University, Imperial College in London and at the just-opened Center For Psychedelic Research at Johns Hopkins Medicine in the USA.

Could there be a risk that psychedelic research, by explaining NDEs in biochemical, rather than spiritual terms, will undermine the hope and relief that many people find in stories of NDEs? If the sensations of bliss, light and love come from neuroprotective molecules rather than being ‘proof of heaven’, is this an area of research best left alone?

Like many working in this field, Dr Frederick Barrett at Johns Hopkins thinks not. “I generally disagree with the premise that explaining the biochemical basis of something undermines the subjective experience, meaning, beauty, terror, or otherwise the value of an experience,” he says. “Does explaining the physics of centripetal acceleration make a rollercoaster any less exciting or terrifying? Not for me, and I would imagine: not for most.”

WARNING:Hallucinogenic drugs such as mushrooms containing psilocybin are a Class A drug according to UK law. Anyone caught in possession of such substances will face up to seven years in prison, an unlimited fine, or both. More information and support for those affected by substance abuse problems can be found atbit.ly/drug_support