Chillingly cool, collected, cunning and clever. Is this the perfect description of a psychopath? For most people, Hollywood movies and popular culture generate such images of psychopathy. Be it Anthony Hopkins as Dr Hannibal Lecter in The Silence Of The Lambs or Psycho's Norman Bates, such characters dominate the public's perception of a psychopath. But how close is this popular image to reality?

The term 'psychopath' originated in the 1800s, from the Greek words 'psykhe' and 'pathos', which mean 'sick mind' or 'suffering soul', respectively. However, this can be misleading.

"Psychopaths might be better conceptualised as people who are dissociated," says criminologist Robert Blakey. "In other words, people who are detached from their own emotions and the emotions of other people. Consequently, they just don't feel much. If they see a person in distress, psychopaths don't feel the distress themselves, so they have less emotional incentive not to harm people."

Blakey believes this dissociation can arise from inheriting an over-sensitive perceptual system. "If you're very sensitive to visible signs of distress and anger in other people, then seeing those signs could become overwhelming for highly sensitive children," he says. "A deficit in one's ability to predict other people's behaviour as a child can be a traumatic experience and, in response, the child's brain may dissociate." In other words, the empathy system shuts down to survive the emotions of others. The irony here is that people born with an excessive capacity to empathise could be more likely to develop psychopathic traits due to losing their full capacity for empathy in their efforts at self-preservation.

This has parallels with a similar theory about autism which, like psychopathy, is a disorder of social cognition. While autism is typically considered a deficit in cognitive empathy, or perspective taking, psychopathy is a deficit in emotional empathy. While the relationship between autism and psychopathy has gained increasing interest due to the shared lack of empathy, research indicates many distinctions between the two conditions. The most relevant distinction is that individuals with autism are not amoral, unlike psychopaths.

Born to be vile?

One way to identify a psychopath is to study patterns in their relationships. Psychopaths generally cannot sustain long-term relationships, so short periods of intensity followed by detachment tend to define their close interactions. While in a relationship, their behaviour is likely to be highly manipulative and selfish, with their needs always coming first.

Not all psychopaths are violent criminals, but most present a threat to our welfare at some level - to one's self-esteem, peace of mind, sexual health or financial wellbeing. There are many theories behind why psychopaths are the way they are. Some believe it is nature, or genetics, that causes psychopathy. Others think it is related to environmental factors. Whatever the cause, medically speaking people with psychopathic tendencies demonstrate certain traits.

Most psychopaths have traits that blend into the fabric of our lives

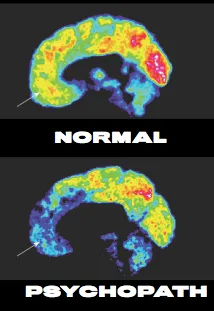

Researchers from Harvard University investigating decision-making in psychopaths took magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans of 50 prison inmates, with the aim of investigating the choices that psychopaths make. They found that people with signs of psychopathy had brains that were wired so that they over-valued immediate or short-term rewards. This desire for instant gratification overshadowed any concern about the consequences of their actions.

They also found that people who scored highly on the parameters of psychopathy - as assessed by a delayed gratification test, an estimation model, and the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL-R) - showed greater activity in the brain's ventral striatum. This is a key part of the reward system. In another study of 164 chimpanzees carried out at the University of Georgia, researchers found that a neuropeptide called vasopressin is associated with the development of socioemotional behaviours related to psychopathic personalities. This adds further support to a genetic element in the development of psychopathic traits.

Environmentally, the impact of socialisation in a child's early years is perhaps equally influential in the formation of psychopathic behaviour. And according to Claudio Vieira, a clinical psychologist based at King's College, London, many different personality disorders - including psychopathic personalities - may result from a combination of genetic elements that shape our personalities, life experiences, and socioeconomic circumstances.

Psychopathic characteristics also vary by culture. A US and Netherlands study comprising over 7,000 criminals exhibiting psychopathic traits revealed that US-based offenders tended to predominantly display the psychopathic trait of callousness, while the Dutch offenders showed greater evidence of irresponsibility. These traits were measured using the PCL-R, which might be interpreted differently in different cultures. Nevertheless, the research raises some interesting areas for further study.

A tough call to make

Be it nature or nurture, the popular image of a psychopath is largely influenced by the ambiguity surrounding its definition and diagnosis. Ironically, psychopathy is not actually an official diagnosis. In the Diagnostic And Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) - the official criteria used to classify mental disorders in the US - the closest condition to psychopathy is Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD).

"APD is characterised by impairments in personality functioning and by the presence of pathological personality traits. However, while offenders with psychopathy often have APD, offenders with APD are not necessarily psychopaths," explains Vieira.

The closest thing to a checklist for identifying a psychopath is the PCL-R mentioned earlier. This comprises a list of 20 character traits and behaviours - such as a lack of remorse or guilt, failure to accept responsibility, shallow emotional response and having many short-term relationships - to help determine if an individual is on the psychopathy spectrum. However, such a checklist does not serve as a 'one size fits all' formula for diagnosis. On the contrary, psychopathic traits can be hidden or subtle. In addition, the chances are that you know people who display some of these traits - that's because the majority of people have psychopathic tendencies. In most people they may be situation-specific or low level, but psychopathic traits certainly aren't restricted to the full-blown psychopath.

"Most people with psychopathic traits blend beautifully into the fabric of our everyday lives," explains Dr Paul Hokemeyer, a clinical and consulting psychotherapist based in New York.

Murderous minority

The lack of a diagnostic tool or a presence in the DSM-5, is partly due to the mystery surrounding psychopathic behaviour. This has led to the predominantly inaccurate media image of a psychopath.

"The nature of cinematic and literary depictions is that they overdramatise the traits found among psychopaths by having them brutally murder a slew of victims," says Hokemeyer. "Top of this list include Javier Bardem's character in No Country For Old Men and Christian Bale in American Psycho. In real life, however, psychopaths seldom murder outright."

Prof Samuel Leistedt and Dr Paul Linkowski, forensic psychiatrists based in Brussels, investigated the history of the cinema-psychopathy relationship in 2014 by analysing 400 films and shortlisting 126 fictional psychopathic characters on the scales of realism and clinical accuracy. They found that psychopaths were often caricatured as sexually depraved and emotionally unstable, with sadistic personalities and eccentric characteristics. Such images aren't necessarily realistic; indeed, Leistedt and Linkowski believe that certain cinematic psychopaths such as Norman Bates in Psycho and Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver are psychotics rather than psychopaths.

While psychopathy is a personality disorder underlined by callousness, recklessness, impulsive behaviour, lying and lack of empathy, psychosis refers to a mental state where the person has lost touch with reality. Psychopathy is typically not associated with any loss in the sense of reality: individuals know where they are and what they are doing. The perception that 'psychotic' and 'psychopathic' are one and the same simply isn't the case. While the former is an outward display of a chaotic personality, the latter is more internal, and difficult to spot. Far from being the crazed, damaged individuals portrayed in the movies, there is mounting evidence that many people with psychopathic characteristics are highly successful. "Psychopaths are very good at seeing which behaviours a system rewards and exhibiting those behaviours. This is one route to career success," says Blakey.

It is not surprising, then, that a 2016 Australian study found that around one in five US corporate leaders displayed psychopathic traits. Psychopaths may be poor at managerial tasks, but they are often adept at climbing the ladder by hiding weaknesses and charming their colleagues. Another potential benefit, according to Blakey, is that the typical psychopath doesn't care about other people's feelings and therefore they don't feel the same compulsion to protect them from negative emotions. As such, psychopaths find it easy to embark on emotional risks that other people might hesitate to take.

Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hospital that has housed a number of notorious patients, including Peter Sutcliffe, Ronnie Kray and Charles Bronson ©

So while at extreme levels psychopathy can lead to antisocial and destructive behaviours, at moderate levels it can offer some advantages. The key difference is between 'clinical' and 'functional' psychopaths. Functional psychopaths know in which context to exhibit their characteristics. When it comes to goals, psychopaths have laser focus, persistent ambition, self-confidence and social charm. According to Hokemeyer, this functional aspect of psychopathy could be the real risk to society.

"The most dangerous trait of psychopaths is their ability to operate in stealth. On the surface, they can appear to be warm, genuine and incredibly charismatic," he says. "But just below the surface of their veneer lies a mountain lion waiting to pounce."

Beyond the Hannibal Lecters of the cinema, the story of the psychopath remains somewhat of an enigma. Scientists know more about psychopathy today, based on case studies and brain research. Yet there is still much we don't know, and the knowledge we do now have is unsettling to many: psychopaths are not necessarily evil but regular human beings with a 'twist' - traits that make them adept at getting their own way. And they live among us every day.

This is an extract from issue 326 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard