Back in 1976, a major medical breakthrough occurred. British researcher Michael Davies discovered that the cause of heart attacks was blood clots forming in the arteries on the surface of the heart. His finding no doubt saved the lives of many patients. Clot- and cholesterol-busting drugs, along with intricate artery-widening procedures, are now used routinely to prevent the artery blockages that deprive heart muscle of oxygen and cause heart attacks.

Fifty years ago, the chance of a UK citizen dying of heart disease – the term that describes the buildup of fatty ‘plaques’ in the blood vessels on the surface of the heart – was four times higher than today, yet heart disease and heart attacks are still Western society’s biggest killer, taking the lives of one in seven men in the UK, and twice as many women as breast cancer.

But now, new technologies and an explosion of understanding about what makes some people more susceptible to heart attacks is changing the game again. Researchers around the world now see the once pie-in-the-sky idea of ending heart attacks as a realistic, if ambitious, target.

Read more about heart health:

- Xenotransplantation: could a pig’s heart save your life?

- HIIT is changing the way we work out, here’s the science why it works

“I think ending heart attacks is definitely something we can now work towards,” says Prof Metin Avkiran, a molecular cardiologist at King’s College London and associate medical director of the British Heart Foundation. “We can definitely have a bigger impact.”

The objective of scientists is clear: to accurately predict who is most vulnerable to heart attacks, and then act early to prevent artery damage and blockage before it threatens lives. A range of game-changing developments are in the pipeline to stop heart disease in its tracks. These include early warning systems of heart attack using genetic data, heart scan analysis by artificial intelligence, and injectable molecular probes that seek out dangerous artery furring.

Over the next few years, lab-manufactured antibodies will be available that block the proteins and inflammation which trigger heart attack. Even a vaccine to prevent heart attacks is on the cards.

Calculating the risk of heart attacks

GPs and heart specialists can already predict your risk of heart disease by making calculations based on risk factors such as age, family history, cholesterol levels and blood pressure, and history of smoking and diabetes. But current risk calculations are crude.

New understanding of genetics is changing that, moving on from calculations that rest on a vague ‘family history’ to accurate scores based on specific genetic traits. To date, researchers have identified 67 different sites in the DNA sequence (called variants) linked to increased heart attack risk, and many of them are inherited. The more variants you have, the higher your risk.

In October 2018, British scientists from the University of Cambridge and the University of Leicester, reported that their new Genomic Risk Score test was significantly more accurate than any other current means of predicting heart disease.

The researchers based the test on a computer analysis of data from half a million people participating in the UK Biobank project. By crunching the correlation between 1.7 million genetic variants and health histories, artificial intelligence analysis came up with an algorithm that could accurately predict heart risk from a genetic profile.

The research – part of a global push to use machine learning to find patterns in big data to improve life expectancy – means it could soon be possible for anyone (even children) to have a standard genotype test costing less than £50, and so have their heart disease risk assessed through the algorithm. Medical and lifestyle interventions could then be used to reduce the chances of those most at risk of having heart attacks later in life.

Other predictive tests are also being developed. This year, an algorithm for patients and doctors to use via an app was launched by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute in Texas, which works with NASA to reduce the tolls of human spaceflight on the body. Its new tool, named Astro-CHARM, combines traditional risk factors with a newly discovered heart risk indicator – coronary artery calcium – into a score predicting the likelihood of heart disease in the next 10 years.

Find a marker

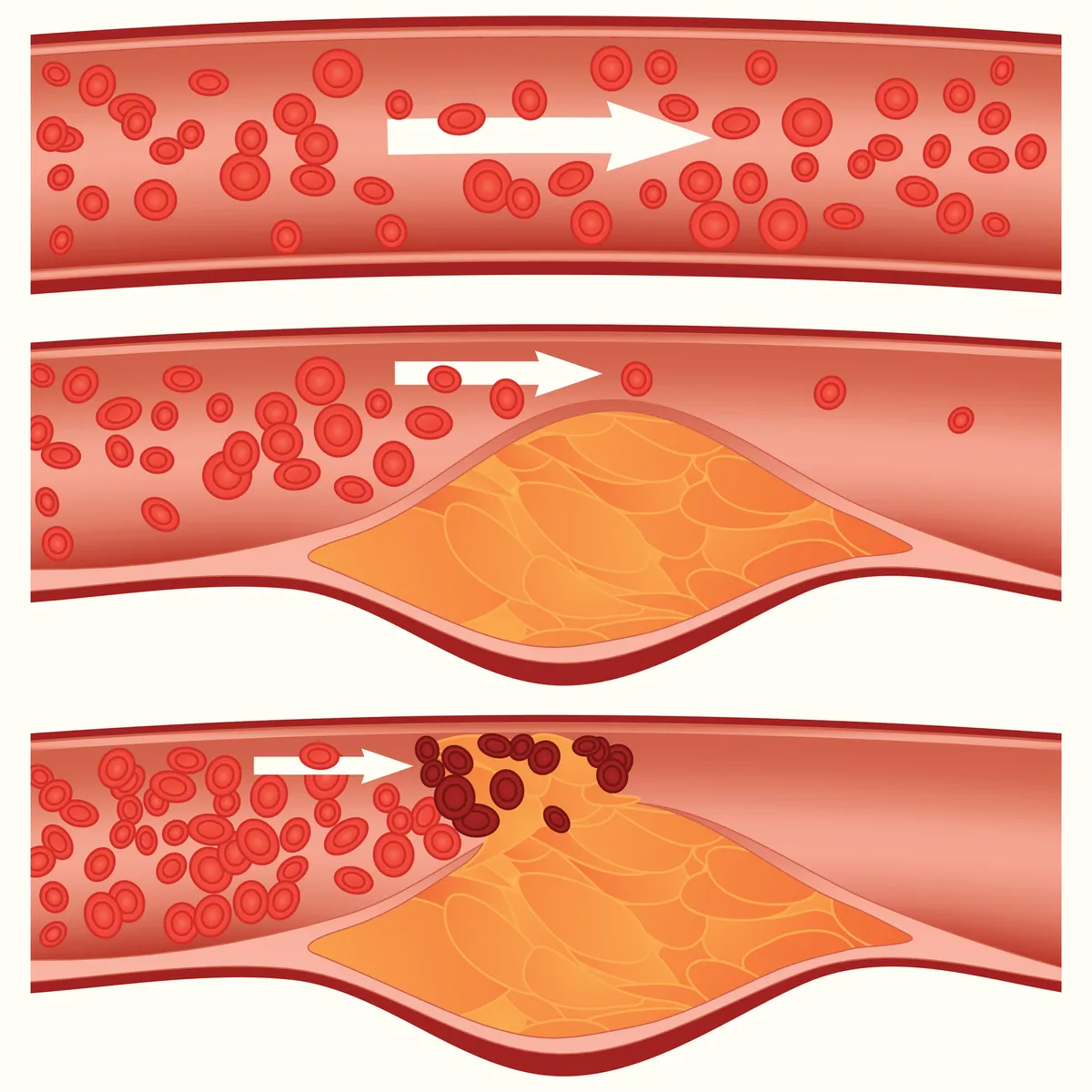

However, the holy grail for heart attack researchers has always been to find some sort of ‘marker’ that could indicate when the fatty (atherosclerotic) plaques lining heart arteries are in danger of breaking off – causing a blood clot in the heart artery, a blockage in blood flow, and then a heart attack. That is why Avkiran believes that some of the most exciting scientific developments in heart disease revolve around scanning techniques that will allow specialists to see exactly what is happening in the heart arteries.

“Up to now, the standard has been coronary angiography, which is essentially a sophisticated X-ray,” Avkiran explains. “This allows you to see which arteries have atherosclerosis [furring], and how blocked the arteries are. But it’s not very good for predicting heart attack risk. You need to be able to see which atherosclerotic lesions might rupture, causing a blood clot.”

Scientists also know that arterial inflammation is a good indicator that atherosclerotic plaques are about to break, but accurately measuring it has been a problem. Now, researchers at the University of Oxford have found that this inflammation causes chemical changes in the fat that surrounds arteries. With this knowledge, they have developed a way of measuring fat changes using a computerised analysis of heart scans.

A 10-year evaluation of the new technique, published in The Lancet in 2018, showed that fat values measured in this way were highly predictive of death from heart attack. A spin-off company is now developing a service to carry out fat analysis of heart CT scans from around the world within 24 hours.

Early warning system

Another innovation to provide early warning of heart attacks involves injecting molecular probes into the bloodstream. The probes latch onto target molecules in the arteries, making underlying chemical processes in arteries visible and measurable on MRI scans of the heart region.

Using this technique, Prof Rene Botnar from King’s College London has found that the presence of a protein called tropoelastin provides a good indicator of plaque fragility, and that monitoring the protein could form the basis of future risk-prediction tests.

A similar technique has been pioneered by scientists at Imperial College London, who demonstrated in animal models that another marker of plaque vulnerability – oxidised ‘bad’ cholesterol (LDL) – could be made visible on CT scans.

They did it by creating an artificial antibody to seek out and bind with oxidised LDL, and linking the antibody to a fluorescent molecular marker. They are now researching the technique on humans, and believe it may also have potential as a means of delivering drugs directly to their arterial targets.

“There are many exciting new approaches to prediction, and I think it’s going to be a combination of these that help people at different stages of their lives to assess risk, not just a single one that changes everything,” explains Avkiran. Identifying your risk of heart attack is one thing. Preventing it is another. And it is artificial versions of antibodies – the proteins produced by the immune system to seek out and neutralise invaders – that are presenting some of the most exciting prospects.

New drugs created from artificial antibodies are indicating they may overtake the success of statins, which have transformed the survival odds of people with heart disease over recent years. Statins are medicines that are prescribed to patients to reduce cholesterol in the bloodstream, slowing the rate of plaque build-up.

Read more:

Already available are new types of cholesterol-busting drug called PCSK9 inhibitors, which are composed of artificial antibodies that target and inactivate a protein in the liver. This in turn lowers the amount of harmful LDL cholesterol circulating in the bloodstream.

But researchers have now discovered a new class of antibody drug that slashes heart attack risk by decreasing inflammation in the arteries. A massive trial across 40 countries of one of these drugs, canakinumab, was reported last year. It found that the drug reduces the risk of heart attack by 24 per cent in people with heart disease. Now there is evidence that targeting inflammation significantly improves outcome for people with cardiovascular disease, the way is open for a whole new front of attack.

The new antibody-based drugs in the pipeline will be expensive. But at the same time, more accurate prediction of those most at risk means that the drugs will can be targeted at those most in need. One of the most intriguing discoveries about how antibodies can help beat heart disease comes from research at Imperial College London, led by Dr Ramzi Khamis, clinical senior lecturer in cardiology. It raises the possibility of a cure, as well as accurate prediction.

Khamis’s focus has been on naturally occurring antibodies. All of us have antibodies that seek out harmful oxidised LDL, and take it away to be dealt with by the liver. Two types of antibody, called IgG and IgM autoantibodies, seem to be particularly good at tackling oxidised LDL.

It seems that some of us have greater numbers of these antibodies than others. Working with scientists from the Netherlands and Sweden, Khamis and his team studied 100,000 people with high blood pressure, and found that those who had heart attacks and the most unstable plaques had the lowest levels of these antibodies. In fact, those with high levels of the antibody had 70 per cent less chance of developing heart disease over five years.

“We found the antibodies provided a massive level of protection,” says Khamis. “Not only might measuring these antibody levels help us assess heart attack risk, but we’re also looking to explore whether we can use the antibodies therapeutically.” Antibody therapies might be used to boost the immune system’s ability to fight oxidised LDL – and might even eventually yield a vaccine to reduce heart attack risk.

“That may be 10 years ahead, but there is that potential,” says Khamis. “But what we’re certainly demonstrating is that the role of the immune system in preventing heart attack is much bigger than previously thought.”

- This is an extract from issue 331 of BBC Focus magazine - Subscribe here

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard