From 1976 to 1986, the residents of California were terrorised by a masked man who raped at least 48 women and murdered a dozen people. His carefully planned attacks suggested military training, but after three decades, the East Area Rapist – also known as the Golden State Killer – seemed to have got away with his crimes. The case went cold.

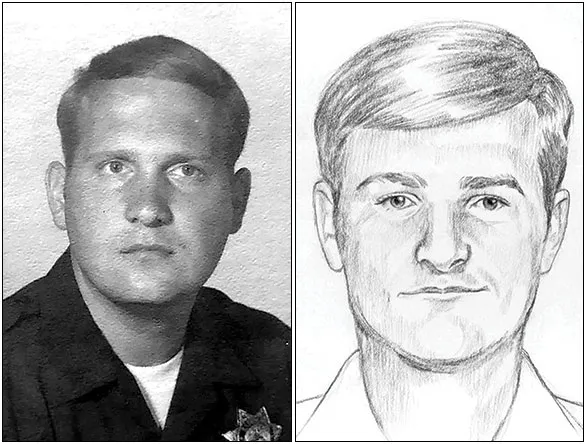

Then on 25 April 2018, law enforcement officials announced that they had arrested Joseph DeAngelo, a 72-year-old Navy veteran and former cop. Investigators explained that semen samples from crime scenes had been used to produce the perpetrator’s DNA profile and search an online database for potential relatives. The list of matches was then used to build a family tree that led to DeAngelo.

While catching killers using ‘genetic genealogy’ might sound like an obvious idea, it is by no means straightforward. “Humans are really similar genetically: if I compared my genome to yours, we’d be 99.99 per cent identical,” says Prof Graham Coop, a population geneticist at the University of California, Davis. “But there are positions in DNA which are variable between individuals.”

Testing methods

Modern genetic tests read the letters of DNA at a selection of positions across the human genome to generate a profile of genetic variants. These single-letter differences represent DNA regions that often vary among people, called ‘single nucleotide polymorphisms’ or SNPs (pronounced ‘snips’).

Personal genomics companies like 23andMe and Ancestry offer ‘direct-to-consumer’ DNA tests that read about 700,000 SNPs. Those variants generate a profile that claim to reveal your family history, ethnic background and susceptibility to disease.

Genealogists who want to study a family tree in detail can upload DNA profiles to a site like GEDmatch, which compares SNPs shared by two people to calculate their genetic similarity. The GEDmatch (GEnealogical Data match) website stores public profiles uploaded by its one million users. Unlike private databases run by DNA-testing services like 23andMe, GEDmatch can be searched by anyone who registers for access, which is how investigators found DeAngelo. “Finding these genetic matches is easy,” says Coop. “The actual work the investigators did is the hard part.”

“If police want a DNA sample, they needyour consent or asearch warrant – at least in principle”

Catching the alleged Golden State Killer was a watershed moment in showing how combining databases and family trees can help crack cold cases. “That really opened up the potential of what we would be able to accomplish,” says genetic genealogist CeCe Moore, who previously focused on cases of unknown parentage, like adoption.

Moore now heads the new genetic genealogy unit for Parabon NanoLabs, a firm that provides forensic services to law enforcement agencies. After DeAngelo’s arrest, Parabon uploaded more than 100 DNA profiles to GEDmatch, with its permission (investigators didn’t ask before uploading the Golden State Killer’s profile).

Moore’s first case was a double murder in Washington State. The male killer’s DNA profile was uploaded on a Friday and by Saturday she had a list of matches for building a family tree that led to a marriage that produced three daughters and one son. By Monday, she had a name for the police: William Talbott II.

Parabon now offers a genetic genealogy service to any agency, not just existing customers. With enough human resources, it could help crack hundreds (maybe thousands) of cold cases. If DNA is available, the approach could be applied to other infamous criminals, such as the Zodiac Killer, who murdered at least five people in the late 1970s and taunted police with letters that might carry traces of saliva.

Ethical concerns

While it may seem that catching bad guys can only be a good thing, there are legal issues to consider, especially privacy concerns for people whose DNA is stored in a database. What if your profile is downloaded and leads to identity theft? Or genes associated with disease or ethnicity are used to discriminate against you when trying to get a job? Such scenarios could occur in future.

For Americans, the issue centres on whether you’re entitled to a reasonable ‘expectation of privacy’ under the United States Constitution. “One of the biggest privacy protections is the Fourth Amendment, which protects individuals against unreasonable searches and seizures,” says Dr Natalie Ram of the University of Baltimore School of Law.

If police want a DNA sample, they need your consent or a search warrant – at least in principle. In practice, they can follow you until you discard DNA in a public place – such as saliva on a coffee cup – then lawfully grab a ‘surreptitious sample’ (that’s how police obtained DeAngelo’s DNA). It’s possible because you waive your rights to property when it’s been thrown away, the ‘doctrine of abandonment’. Even uploading your profile to a database might be considered ‘abandonment’ under US law: inthe 1970s, the Supreme Court said the Fourth Amendment didn’t cover data voluntarily shared with a third party.

What about here? For now, UK law only applies to DNA profiles for convicted criminals. “Our National DNA Database is quite well-regulated in terms of who gets on it, who’s allowed to access it,” says Prof Carole McCartney of Northumbria University. “But there’s no rules about private companies – it will come down to their terms and conditions.” The European Union’s recent General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) law gives citizens greater control over how their information is handled, but McCartney thinks it’s accepted that the police can use genetic data. British police could search GEDmatch profiles to track down suspects with American relatives.

Over-reach can happen through ‘function creep’ – when the use of new technology (like DNA databases) is sneakily stretched beyond its original purpose. This can cause an invasion of privacy, as illustrated by the National DNA Database, which initially added people who had been arrested but didn’t remove them after release. The case ended up in the European Court of Human Rights and led to the Protection of Freedoms Act.

The danger is compounded by misplaced trust in the forensic process, which is vulnerable to errors: investigators can cause contamination while collecting DNA, or mix up samples while processing. Despite what’s seen on TV police dramas, DNA is rarely featured in trials, which is when experts explain its reliability. “DNA evidence is seen to be so powerful, it’s very difficult to defend yourself if you’ve got your DNA matched,” says McCartney.If you’re a law-abiding citizen with nothing to hide, you may still be asking yourself the

question: where’s the harm in using my DNA to help catch a killer? The answer depends on your personal ethics and how you weigh the benefits for victims against potential costs to other people.

One key issue is informed consent. “I’m really not confident that people understand or are even aware that their genetic genealogy can be used for criminal or forensic purposes,” says Dr Benjamin Berkman, a bioethicist at the US National Institutes of Health. Until recently, he adds, information about such disclosures was ‘buried in the small print’.

“In contrast to the criminal justice system, in the media you’re often guilty until proven innocent”

Berkman says the problem stems from expectations. People signed up to GEDmatch to study their family history, not aid law enforcement. And although the site’s original terms of service did warn users that DNA profiles could be used to help identify people related to victims or criminals, some members didn’t realise that until DeAngelo’s arrest hit the headlines, then felt so misled that they deleted their accounts. GEDmatch has since revised its terms to explicitly state that profiles could help identify a perpetrator of a violent crime.

Informed consent also means being conscious of the impact ‘familial searching’ could have on others. “I like to think about it in terms of your cousin getting arrested,” explains Berkman. “Some would say ‘The fact that my DNA indirectly helped to lead him to justice, it’s fine’, but you can imagine other people who would feel guilt or conflict about having caused a relative to go to jail.”

False positives

When someone is under suspicion for a crime, their name can get leaked to the press – and in contrast to the criminal justice system, in the media you’re often guilty until proven innocent. That’s what happened to US film-maker Michael Usry Jr, who was investigated in 2014 for a 1996 murder, based on a partial match to his father’s DNA following a familial search of a database (the FBI even secured a warrant for cheek swabs). Even if you’re later cleared, as Usry was, being branded a killer could still haunt you for the rest of your life.

“At the end of the day it’s your genome,” Berkman concludes. “And if you want to learn more about your ancestry or your genealogy or your health,

I don’t know that other people get to tell you what you can and can’t do with your DNA.”

But for genetic genealogist CeCe Moore, the ethical balance tips toward the victims of crime and their families. “These families have often been waiting for decades for justice and some sort of closure,” she says. “And we are finally able to provide that through this new technology and techniques.”

This is an extract from issue 326 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard