The debate on the impact of food on health is something of a contact sport. Food is so deeply imbued with personal and cultural meaning that it can be difficult to remain objective. Food is complex, and increasingly so.

While a little over 60 years ago you might have been able to choose from a glass of orange juice, orange cordial or orange soda, you can now also opt for an orange-flavoured energy drink, orange-flavoured vitamin water, orange-flavoured protein water, orange-flavoured water with added magnesium…

Modern food processing has certainly given us more options, but what do we know about the impact of these processed foods on our mental health?

First, let’s get clear on the different levels of food processing. A research group recently codified the principles of what constitutes an ultra-processed food (UPF), using something called the NOVA classification.

Here, food is divided into one of four groups based on the nature, extent and purpose of food processing.

- Group 1 includes unprocessed or minimally processed foods, like fresh, squeezed, chilled, frozen or dried fruits and vegetables; pasteurised milk; grains; legumes; and fresh or frozen meat and fish.

- Group 2 features processed cooking ingredients like sugar, molasses, honey, vegetable oils, butter and lard.

- Group 3 are called ‘processed foods’ and include canned or bottled fruits, vegetables and legumes; salted and smoked meats; tinned fish; unpackaged breads; cheeses; and salted or sugared nuts.

- Group 4 is classed as ‘ultra-processed foods’, which features those foods made with five or more ingredients, or those ingredients that would not commonly be used in food preparation at home. So we’re talking about things like mass-produced breads, biscuits and cakes; breakfast cereals; fizzy drinks; ready-to-heat pizzas, pies, pastries and pastas; instant noodles and soups; and nuggets, sausages and burgers.

It is fair to say that ultra-processed foods are now dietary staples in the UK and US. The UK leads the way in the consumption of UPFs across Europe, with 55 per cent of UK adults’ daily calories coming from ultra-processed foods, mostly in the form of baked goods (cakes and biscuits), confectionery, processed meats and soft drinks, and that figure is growing. Americans are slightly ahead of us, with ultra-processed food and drinks making up 57 per cent of their daily calories.

And children are even bigger consumers. A recent 17-year prospective study of the diets of over 9,000 UK children and young people aged 7 to 24 years old found that one in five were consuming over 78 per cent of their daily calories from ultra-processed food and drinks. The main categories in the high-consumption group were fruit-based or fizzy drinks, ready meals and ready-made cakes and biscuits.

Read more:

- Eating ultra-processed foods could increase risk of type 2 diabetes, study finds

- Ultra-processed food and the risk of death: will fish fingers and fizzy drinks kill you?

Why ultra-processed foods are bad for your brain

But food processing has done much good. Food that lasts longer is cheaper for the consumer. UPFs are convenient to prepare and eat. And, by design, they taste good. So what’s the problem?

Though one glass of squash isn’t going to kill you, there are reasonable grounds to be concerned about the majority of our diets consisting of these foods. This is because the nature of processing means that brain-healthy nutrients, like vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, essential fats and fibre, are lost.

In order to extend shelf life and palatability of UPFs, additional sugar and fats are added, which may have negative consequences for metabolism, blood glucose control and brain health. Finally, and most importantly, the convenience of these foods means that they increasingly push more nutritious but more difficult-to-prepare foods out of our diets.

For example, during the same period that US consumption of ultra-processed food and drinks increased from 53.5 to 57 per cent of daily energy intake, consumption of minimally processed foods dropped from 32.7 to 27.4 per cent.

The problem is, the more our diets are made up of UPFs, the lower our daily nutrient intake. For example, a 2015 Brazilian study assessed the diets of 32,898 individuals over the age of 10 and showed that the consumption of UPFs was inversely correlated to the intake of vitamins B3, B6, B12, D, E, copper, iron, phosphorus, magnesium, selenium and zinc. A more recent Mexican study of 10,000 people found the same thing: the higher the consumption of UPFs, the lower the intake of B vitamins, vitamins C and E, and minerals.

It is this nutritional displacement, I think, that explains why high UPF consumption is linked to worsening brain health, with measurable effects on mood and cognition. A French study of over 26,000 people, who were assessed at baseline and then followed up around five years later, revealed a significant association between UPF consumption and depression risk.

A study of 14,000 Spanish university graduates found the same thing: those individuals who ate the highest amounts of UPFs had the greatest risk of developing depression in the intervening decade.

We are still in the early days of this research, yet the studies seem to show that higher consumption of UPFs is correlated with increased risk of depression. Though there is evidence of a two-way relationship between depression and increased UPF consumption (poorer mood may be both a cause and consequence of poor diet), around a third of the studies in a recent review indicated that greater UPF consumption was a driver of worse mood.

And similar associations have been found in children. A 2021 study of more than 8,000 UK secondary school children was published in the journal BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health. It spotted a link between higher consumption of fruits and vegetables and improved self-reported mental wellbeing.

But that probably means they came from wealthier, less stressed households too, right? Yes, probably, but when the results were adjusted to account for confounding factors such alcohol consumption, smoking status, household income markers, and adverse effects such as bullying, the association held – more fruit and veg was linked to better mental health. But if you need more convincing, we can take a look at the brains of people on Western versus minimally processed diets.

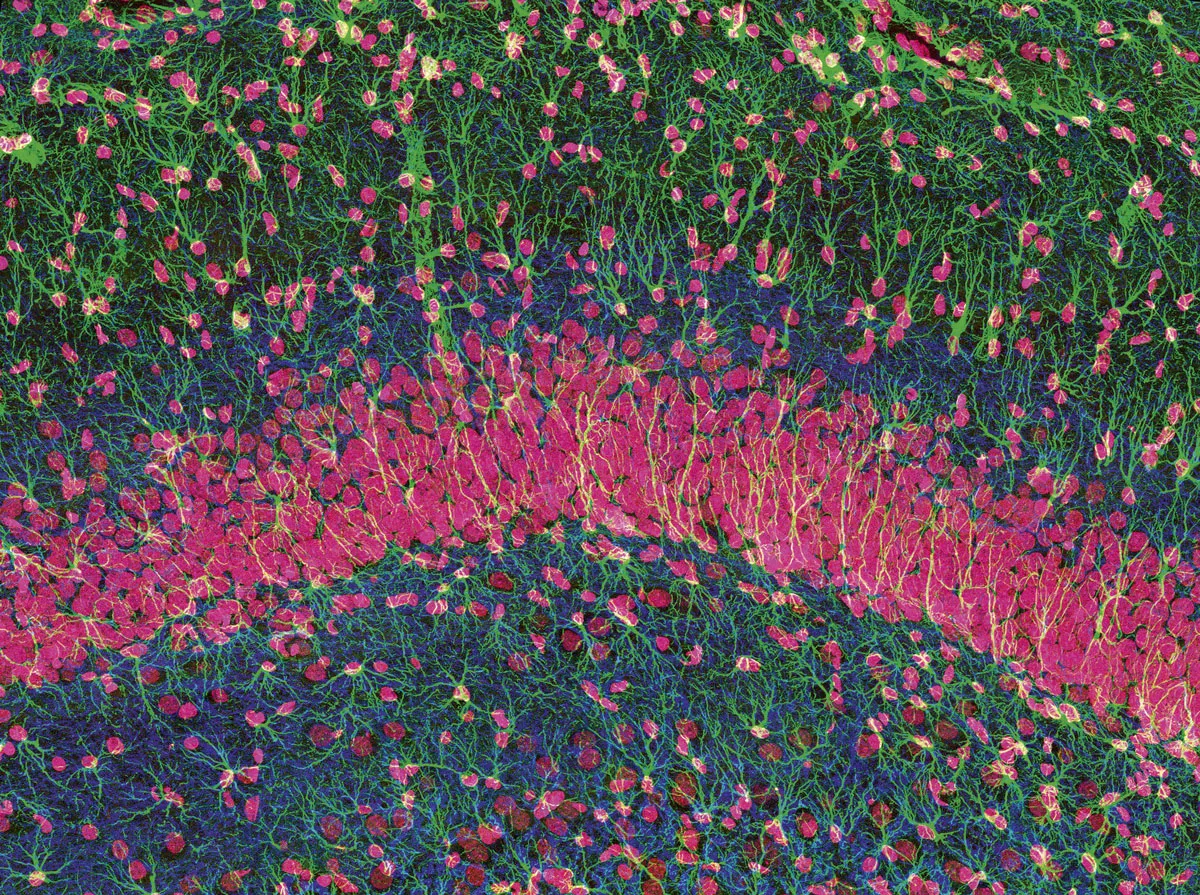

A study published in the journal BMC Medicine in 2015 looked at the brains of older people over the course of four years. It found that the healthier the diet, the larger the brain’s memory centre, the hippocampus. This is a good thing, as it generally means there are more connections – a feature known as cognitive reserve – which is linked to protection from neurodegeneration.

A separate study published in Royal Society Open Science in 2020 showed that negative effects on the brain emerge within days on a Western-style diet, that’s high in UPFs. Here, 110 healthy people, who typically ate a nutritious diet, switched to a Western-type diet for just a week. During that week, they were asked to eat two Belgian waffles for breakfast a few times, and to consume a couple of takeaways. Compared to the control group, the Western-style diet group did worse on hippocampal-dependent learning and memory tests, and also had poorer appetite control.

The hippocampus is the part of the brain that is substantially damaged in Alzheimer’s disease. The fact that measurable brain damage can be induced by just a few days on a diet that many people eat habitually is concerning.

Read more:

- Vegan fast-food: why plant-based alternatives are good for the planet but not your health

- 5 things you probably didn't know about processed food

How not eating enough nutrients is harming children

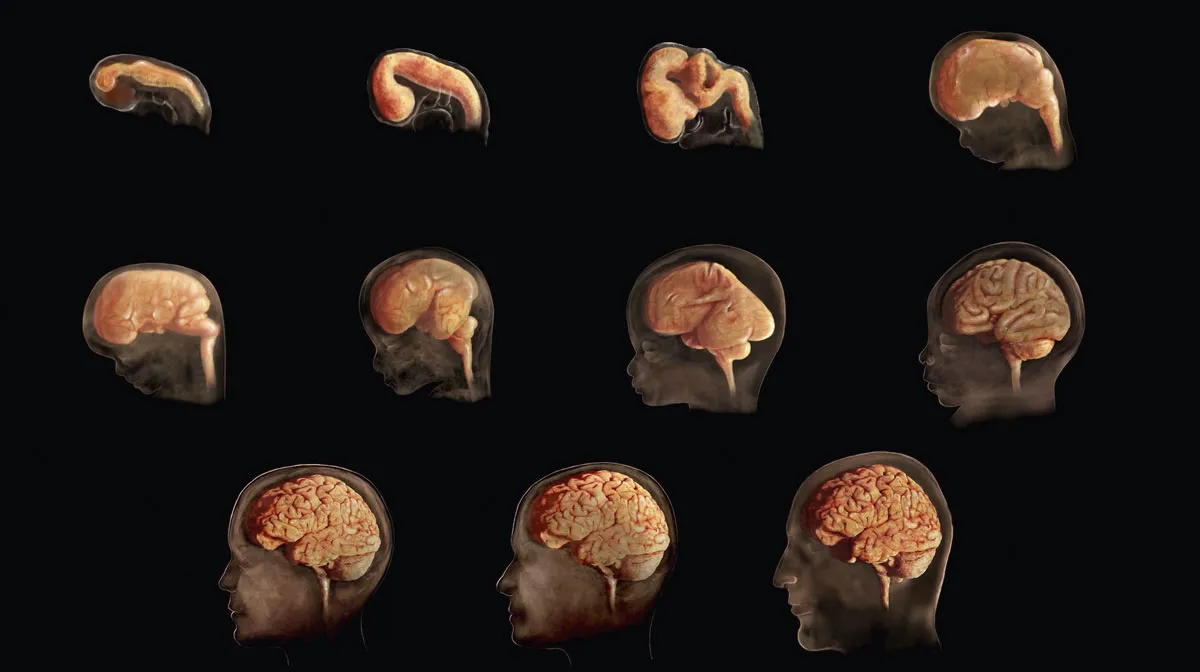

However, our ever-growing dependency on UPFs is likely to be having detrimental effects on brain development at the start of life, not just the end of it. According to a review on the links between maternal diet and child health published in The Lancet in 2018, the Western diet is typically deficient in magnesium, folate and iodine, which are key nutrients for brain development.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes iodine deficiency as the single most important preventable cause of brain damage worldwide. At the extreme, iodine deficiency during pregnancy leads to a condition in children called congenital hypothyroidism (previously known as ‘cretinism’), which present as significant impairments in physical and mental development.

However, less severe iodine deficiency is linked to intellectual and cognitive deficits across populations. Insufficient iodine in the first 14 weeks of pregnancy permanently suppresses a child’s IQ. The WHO notes that people who live in areas of iodine deficiency have IQs up to 13.5 points lower than peers in non-deficient areas.

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a study currently following the health of thousands of people born in 1991 and 1992 in the former county of Avon. One research team analysed the cognitive outcomes of the children of 958 women, while also recording the mothers’ iodine levels during their first trimester of pregnancy.

They found that 67 per cent of the women had mild to moderate iodine deficiency. And these deficiencies were linked to poorer cognition in children. If this has you worried about your levels, seafood and seaweed are good sources of iodine, along with dairy products and eggs.

“Low maternal iodine status was associated with an increased risk of suboptimum scores for verbal IQ at age eight years, and reading accuracy, comprehension, and reading score at age nine years, even after adjustment for many potential confounders,” the researchers concluded. “Furthermore, our results suggest a worsening trend in cognitive outcome with decreasing maternal iodine status.”

And it’s not just iodine that’s important for our grey matter. We know that omega-3 fats are essential for brain development, and oily fish is one of the best sources of this nutrient. But most adults in the UK fail to meet the recommendations for oily fish consumption, including pregnant and breastfeeding women. A separate analysis of ALSPAC data found a relationship between maternal fish consumption as measured at 32 weeks’ gestation and child IQ. The more fish a mother ate during pregnancy, the higher her child’s IQ.

Is there an antidote to ultra-processed foods?

These associations seem especially meaningful when we note that the Flynn Effect, the observation that global IQ consistently increased over the course of the 20th Century, has been in decline in Western countries such as Norway, Denmark, Germany, Australia and Britain since the 1990s. In fact, one report states that high IQ scores in the UK have been ‘decimated’ in recent years.

The evidence is accumulating that an overall dietary pattern dominated by ultra-processed foods is detrimental to our physical and mental health. So, what can we do? One solution is to make processed foods healthier, and this is certainly an option that manufacturers like the sound of. Always resourceful, the food industry is now offering us solutions for problems that, arguably, they have created, in the form of ‘functional foods’.

Functional foods are a subtype of UPFs that have had some of their nutrients added back in. For example, snack bars and yoghurts with added fibre. The global functional foods market, which is dominated by brands such as Kellogg’s, Nestle, Danone and Pepsico, is currently estimated to be worth $280bn (£230bn approx) and predicted to grow by 8 per cent by 2030.

It’s kind of brilliant. They produce, market and sell foods that are nutrient-poor, and then sell us the nutrients back in another product. It’s business genius!

In the context of a nutrient-poor diet high in UPFs, functional foods have some benefit, particularly for fussy or picky eaters who might only consume a limited range of foods. However, there are hundreds or probably thousands of nutrients in wholefoods that have not been isolated by food scientists, so simply cannot be added to manufactured foods. A vitamin teabag can’t give you what an apple can.

We need a multi-faceted approach that seeks to improve the food environment at every level, from the individual to the whole of society, from pre-conception to old age. And that needs to happen sooner rather than later. The future of our brains depends on it.

Read more: