When we die, nature wastes no time in disposing of us. Within minutes, our enzymes get to work on our tissues, breaking down proteins and fats. Not long after, microbes that once inhabited our gut move through our body via our blood and begin the process of putrefaction that liquefies our organs.

Our soft tissues usually disappear completely within five years to a decade, leaving nothing but bones and empty spaces – exactly what archaeologists expect to find when they’re dealing with human remains.

That’s why, when an archaeologist turns over a skull, the last thing they imagine being confronted with is a brain. But it does happen. When the conditions are exactly right, when death occurs in a particular way, the brain can survive for hundreds and sometimes thousands of years. It may be shrivelled, waxy, brittle or glassy. But key structures like the brain stem, the characteristic grooves and folds of brain tissue, and even ancient proteins can be preserved in centuries-old organs.

Some experts now think that brains are being preserved more often we realise; it’s just that archaeologists don’t always have the experience to recognise them. “Now that there’s more literature about it, more of these brains will come to light and we’ll be able to put them at different points on the time scale of millennia and analyse them,” says neurologist Dr Axel Petzold, who worked on the brain of a decapitated Yorkshire man (see below).

What, though, can preserved brains reveal about the bodies they once inhabited? Could they help us to uncover secrets about the past, solve mysterious deaths or catch ugly crimes? And, perhaps most intriguingly, how did these squidgy masses of fatty tissue manage to survive the ravages of time at all?

Ötzi the Tyrolean Iceman

Age: 5,300 years

Location: Tyrolean Alps, Austria

Discovered: 1991

Considered something of a record-holder in the preservation stakes, the Tyrolean Iceman dubbed ‘Ötzi’ endured 5,300 years on a ridge high in the Tyrolean Alps before being discovered by a pair of German tourists in the early 1990s. He was so solidly frozen into the ice that he had to be dug out with a pneumatic drill, ski poles and ice picks.

Though half-decomposed, he was doing well for his age, so much so that scientists were able to piece together everything from what he ate for his last meal (ibex), to what his underwear was made of (leather), as well as his genome.

Ötzi did keep something to himself though: his brain has never been examined by human hands or eyes. We do however, have scans and samples from it. Scientists led by Dr William Murphy at the University of Texas imaged the skull by X-ray and CT scan, revealing a brain that was shrunken, but preserved by what’s known as adipocere or ‘corpse wax’. This solid, waxy substance develops in the months after death through chemical reactions involving fats and water.

Compared to soft tissues elsewhere in his body, Ötzi’s brain was better preserved, supposedly due to higher levels of water that helped form the corpse wax. “The fact that brain tissue is relatively protected from the ambient environment by the skull provides an opportunity for a higher-humidity environment for the brain than that for the rest of the body,” the scientists wrote. “This difference could lead to relatively greater adipocere formation in the brain.”

Separately, a European team of scientists took two tiny tissue biopsies from the Iceman’s brain, studying them under the microscope to reveal neuron-like structures and red blood cells, and extracting over 500 preserved proteins, some of which they could match to his genome sequence.

They found numerous proteins related to stress responses and bleeding. “These proteins could support the theory of an injury of the head near the site where the samples have been extracted,” they wrote, delivering a potentially devastating blow to the previously favoured theory of Ötzi’s death: a fatal arrow wound.

Read more about ancient humans:

- The Babylonians were using Pythagoras’ Theorem over 1,000 years before he was born

- How scientists are using cosmic radiation to peek inside the pyramids

Decapitated Yorkshire man

Age: 2,600 years

Location: Yorkshire, UK

Discovered: 2008

Sometimes unremarkable sites conceal remarkable discoveries. Such was the case in 2008, when archaeologists working at a dig on a University of York campus uncovered an Iron Age farming landscape littered with pottery and flint.

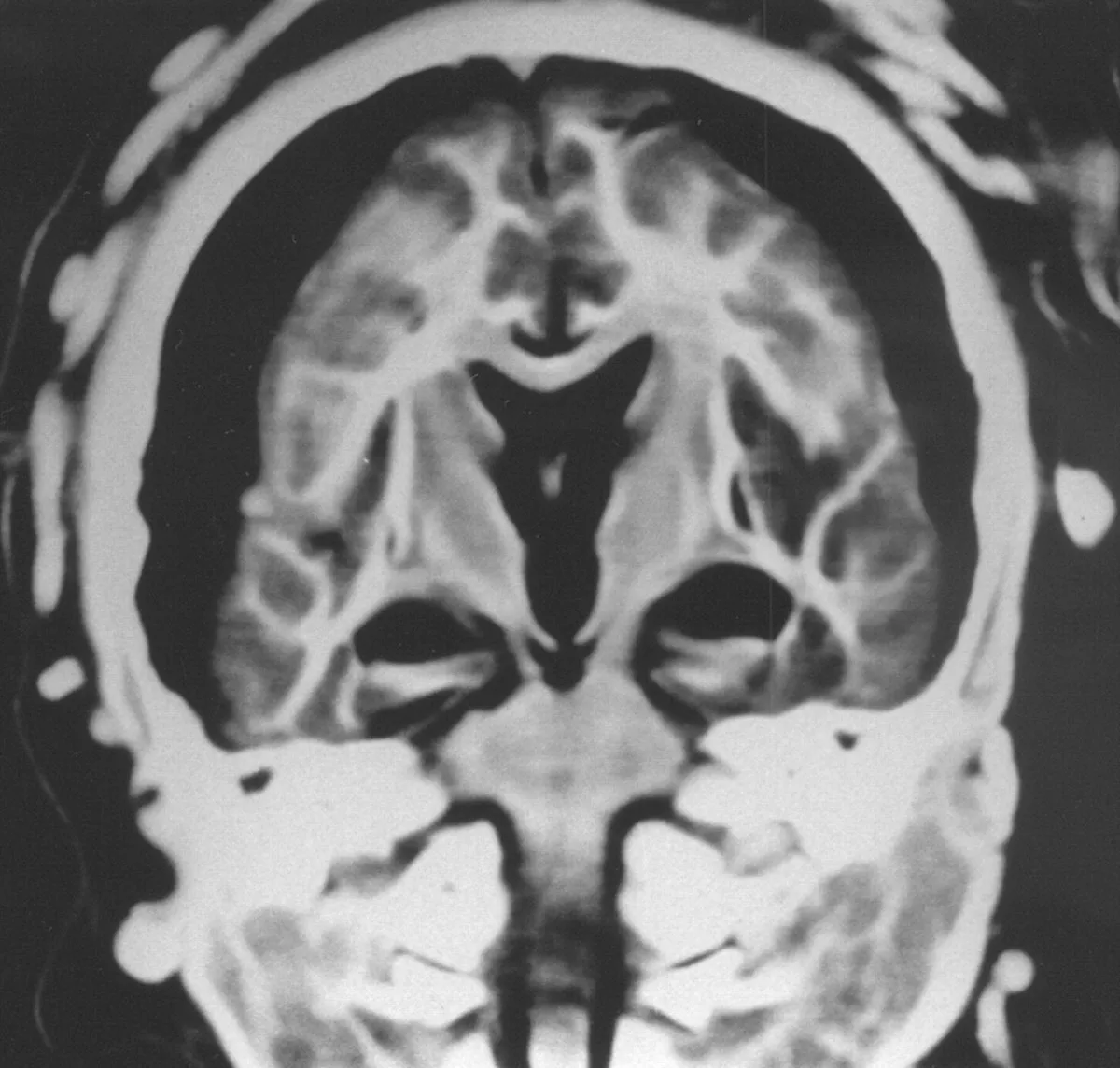

The most surprising find was in a wet pit marked by a single stake: a decapitated human skull. It wasn’t until the skull was being cleaned back at York Archaeological Trust’s headquarters that something was found rattling around inside it.

Although shrunken, scans confirmed that the beheaded man’s skull contained a brain. This was puzzling, since the conditions didn’t offer anything to suggest what would have preserved it and there was no hair or other soft tissue. When the skull was eventually opened, the brain tissue turned out to be very acidic.

Petzold, a neurologist at University College London, was present at the time and remembers seeing a knife “turned black with erosion” as it cut into the brain.

One theory is that the victim’s head was dropped into acid. This could explain why the 800 or so proteins that Petzold later extracted from the tissue were so well-preserved. “In the laboratory, if I want to preserve proteins, I can just put them in acid,” explains Petzold.

This theory also tallies with results published in 2020 showing that more of the proteins in the outer parts of the brain survived, compared to the inner parts, suggesting that some unknown substance diffused in.

There’s more to the mystery though. When Petzold’s team was trying to extract the proteins, a lot of them seemed to be stuck inside an insoluble brown muck. Then, in their long-term decay experiments on the brain tissue, protein levels started going up rather than down as they would have expected.

It seemed the proteins had aggregated and were now being released. Petzold explains the long nerve fibres in the brain contain very flexible proteins that can change their shape. “We think that’s how the brain got preserved,” he says. “Over time they just folded in or aggregated.”

Ordinarily, proteins don’t aggregate like this, but mutations in one protein suggested that the decapitated man was in the grip of a rare neurological condition known as Alexander Disease, which causes seizures and problems with movement and speech. The disease is also linked to protein aggregation.

It’s a little speculative, but Petzold says these results provide a plausible explanation as to why the man was killed: his symptoms, which were not understood at that time, may have marked him out as a mad man.

Vesuvius victim

Age:1,492 years (79 AD)

Location: Campania, Italy

Discovered: 1960s (Brains reported 2020)

In the first century AD, a cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius devastated the Roman town of Herculaneum. Archaeologists discovered 330 bodies here, and more at Pompeii and other Roman settlements, mainly those of people who died when their homes collapsed on them.

One victim – left like a macabre museum exhibit – remains forever sheltering in his bed, his skull scattered about like pieces of broken pottery. His head, it seems, exploded in the heat of the volcanic eruption and resulting ash cloud.

The victim’s skeleton was discovered in the 1960s, but is still giving up its secrets. “Almost 60 years later, during a site investigation, I saw something shining within the volcanic ash filling the skull,” says Pier Paolo Petrone, a researcher at the University of Naples Federico II. “A glassy black material.”

The black stuff was stuck to the insides of the skull fragments, leading Petrone to the natural conclusion, in a 2020 study, that whatever had produced it had come from inside the victim’s head.

Petrone’s team set out to prove that it was in fact ‘vitrified’ brain tissue that had been turned to glass in the heat of the volcanic eruption and then buried. As Petrone explains, “I proposed that the brain was preserved due to the rapid drop of the initially very high temperature of the first pyroclastic surge.” Vitrification, which turns a liquid to a solid, but without forming crystals, is also used to cryopreserve frozen eggs, sperm and embryos in fertility treatments.

The study incited some nit-picking among archaeologists over vitrification temperatures, as well as about preserved ancient proteins that Petrone’s team claimed to have identified in the glass – none of them matched the proteins found in Ötzi’s or the beheaded Yorkshire man’s brain. Petrone says the preservation of the structures in the ancient brain is exceptional however, and will allow it to be studied “at a level of resolution never seen before.”

Andean mummies

Age:500 years

Location: Llullaillaco Mountain, Argentina

Discovered: 1999

High in the Andes, a combination of below freezing temperatures, low oxygen levels and humidity naturally mummifies those who die in the mountains. These conditions contributed to the extraordinary preservation of three frozen children sacrificed by the Incas. After they were recovered in 1999, scientists wrapped them in plastic inside individual freezers to maintain their humidity and keep them from disintegrating.

The children (two girls and a boy) apparently froze soon after death, halting decay before it could take hold. In 2016, explorer Johan Reinhard described his surprise when pulling back a blanket covering the youngest girl’s head. “None of us had expected to see her face, much less that it would exhibit a pensive stare,” he wrote.

Almost all of the children’s organs appeared in scans, with blood still present in hearts and lungs, making them some of the best-preserved mummies ever found. However, their brains have never been directly sampled.

In 2003, a team including Reinhard published CT scans of the children’s brains. The spaces between their skulls and brains showed the brains had shrunk (as with the Iceman, although perhaps to a lesser extent) but the researchers were able to tell the grey and white matter apart. “The fatty tissue of the bodies and the white matter… were visibly white on the CT scans,” they wrote. They suggest the white matter appeared like this due to reactions in corpse wax that combine fatty acids and minerals to produce soap.

As for the cause of death, head trauma was ruled out by the CT scans, leading scientists to propose they were buried alive or suffocated. More recently, analysis of the oldest child’s hair suggests she was plied with drugs and alcohol to keep her sedated. According to a 2015 study, the Incas rarely carried out bloody rituals as bloodshed would have made the sacrifices ‘incomplete’.

Bronze Age fire victims

Age: 4,000 years

Location:Kütahya, western Turkey

Discovered:2010

There’s something ‘special’ about the earth at Seyitömer Höyük in Turkey, insists biologist Meric Altinoz. In his view, it’s no coincidence that the same soil that preserved the brains of four Bronze Age fire victims also preserved lentil seeds that he was still able to germinate 4,000 years later. “[It’s] a unique environment, which somehow preserved both the brains and the seeds,” Altinoz says.

Seyitömer Höyük is an ancient burial mound thought to have been formed over the site of an earthquake and fire. Four of the partially burned skeletons uncovered there were found with their brains poking out of their cracked skulls. Though he now works with neurosurgeons, Altinoz was part of a Turkish team that, in 2014, analysed the preserved brains along with the soil they were buried in – clay that supplied the nearby city of Kütahya’s ceramic industry.

Altinoz refers to the shrunken and hardened Seyitömer brains as “bioporcellate” – not dissimilar in texture, he notes, to the ceramics that were produced in the local area. Their fat content showed clear evidence of corpse wax, but when the researchers looked in detail at their mineral composition, they found that they contained high levels of alkaline minerals, such as potassium and magnesium, which are present in clays, as well as boron, used in tile-glazing, but also mummification.

“It was even higher than the boron level that was used for the mummification of Egyptian brains,” says Altinoz.

While water is usually thought to be important for forming corpse wax or adipocere, here, there was only fire. The team therefore theorise that the brains boiled in their own tissue water after death. Similar high-temperature reactions are used in industry to produce stearic acid – the main fatty acid component of adipocere – from animal fats. The clay minerals in the soil would also have helped make the wax harder and more brittle.

What about the boron, though? Although it’s just speculation, Altinoz remains convinced it played a role in keeping the brains and the seeds preserved – boron is known to help stop plants from rotting, he points out. Unfortunately, he was never able to glean much from the lentils, because his fridge broke, killing the last remaining freshly germinated samples.

La Pedraja mass grave

Age: 85 years

Location: Villafrance

Discovered: 2010

Even when burial sites are relatively modern, archaeologists don’t expect to find brains in them, much less 45 of them. Yet a team working at the excavation of La Pedraja mass grave, near the city of Burgos in northern Spain, uncovered the largest and best preserved collection of brains in the world.

The 45 brains belong to the victims of fascist rebels supporting General Franco’s 1936 military coup, just a few of the approximately 130,000 Spanish people executed at the time. Many more would die in the Spanish Civil War that followed.

Sadly, most were never returned to their families and remain in mass graves. At La Pedraja, 104 bodies were exhumed from the 1.5m-deep pit by the Aranzadi Society of Sciences, aided by volunteers. The grave was still new enough to be classed as a crime scene and was scrutinised by forensic experts as well as archaeologists.

“When we dug the pit it still smelled of decomposition 80 years later,” says Dr Fernando Serulla, one of the forensic experts from the Hospital de Verin who attended the site in August 2010. Serulla personally found at least five of the 45 preserved brains, which had shrunken to less than a third of their original size and were greasy to the touch.

Serulla went on to lead a 2016 study on the brains. The main reason they remained in such good condition, while the bones deteriorated badly, he says, was the presence of a lot of water. “The perpetrators dug in soft, moist earth and left the bodies between July and September 1936, months that were unusually rainy.”

As in other cases, it’s thought the water contributed to the chemical reactions that turn fatty tissues to corpse wax, protecting the brains. Serulla also thinks that blood emptying from gunshot wounds to the head prevented the putrefaction by bacteria that would normally start soon after death.

Besides being an interesting case of exceptional preservation, Serulla says studying these brains opens the door to investigation of serious crimes such as torture. “We’ve managed in one of the cases to show that the person suffered brain injuries several days before he died,” he says.

Only 18 people killed at La Pedraja have been identified, but all the victims have now been reburied together at a cemetery, beneath a memorial.

- This article first appeared inissue 367ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here

Read more about archaeology: