Paul Erdős was a strange houseguest. The brilliant mathematician, born in 1913 in Austria-Hungary, would show up on friends’ doorsteps with a fraying suitcase and an orange bag from a department store in Budapest.

Not only would he expect them to do his laundry, but he would wake them in the early hours of the morning, looking for a mathematical collaborator. He would declare “my brain is open”, while asking if theirs was the same.

Erdős spoke a language that reflected his obsession with maths. If someone left the field, they’d “died”, while if someone actually died, they’d merely “left”. He exclaimed that prime numbers were his “best friends”.

He published more papers than any other mathematician in history, but spurned full-time job offers, instead living for 50 years as a nomad. He went from one collaborator’s house to another, looking for those whose brains were open.

His obsession with numbers, theorems and mathematical problems made Erdős one of the most beloved and respected people in the field of maths, despite overstaying his welcome in a lot of people’s homes.

While obsessions as extreme as Erdős’s may be rare, they are a hallmark of human existence. They can drive us, help us accomplish goals, develop skills and amass knowledge.

Pop culture tells us obsession is a good thing. Books like the entrepreneur Grant Cardone’s Be Obsessed Or Be Average sit on self-help shelves in bookshops.

“We have this category of obsession that’s related to genius and talent, to sports and perfection. We live in a society that is devoted to it, where we’re supposed to be obsessed,” says Lennard Davis, an English professor at the University of Illinois.

Harmless obsessions see us learn everything about a favourite band or celebrity. But some of us fall victim to obsessions that become harmful. For example, when a celebrity obsession turns into stalking, or when a concern about fire leads us to ritually check the oven many times before leaving the house.

So what is it about the human brain that means an idea can shift from a thought to an obsession, and is there a difference between those obsessions that society deems healthy and those it considers not?

The role of dopamine in obsession

Dopamine is one of the brain’s neurotransmitters, a chemical messenger that relays signals between neurons and brain areas. It’s mostly linked to a sense of reward and pleasure, conveying the message that this is behaviour worth repeating, though this is just one of many of its functions.

Typically, a dopamine surge follows success, regardless of whether that’s in sport, work, or a video game. Dopamine isn’t the only neurotransmitter in the reward pathway, but it is the key neurotransmitter involved in wanting the reward, and therefore motivating people to pursue it.

Our expectation of a reward could be cued by loading up a web page to check stock performances, getting a notification from work, or thinking about ticking a workout off our exercise schedule.

But every time pleasurable activities are experienced, powerful self-regulating mechanisms kick in to bring dopamine levels back down again.

Dopamine boosts are strongest from novel activities (the first time you try a new type of food, for example), and consequent hits are never as rewarding because of the way your body and brain regulate the presence of the neurotransmitter.

Therefore, most pleasurable activities don’t escalate to obsessions, because they produce small enough dopamine spikes that we enjoy them and then decide to pursue something new in order to experience the boost again.

However, if we repeat the exposure to the thing that gives us pleasure, the self-regulatory mechanisms that make us feel low afterwards can get stronger and last longer. Then, “we need more exposure to our drug of choice to get the same effect”, writes psychiatrist Prof Anna Lembke in her book Dopamine Nation.

This is called neuroadaptation, and it’s how we create tolerance to certain stimulants. For a chocoholic, one bar doesn’t do it anymore. A workaholic pursues longer hours.

How do addictions form? And how much do our genes matter?

Sometimes, obsessions can become addictions. Addiction is defined by a continued or compulsive pursuit of a substance or behaviour, despite its harm to oneself or others.

For a long time, the term ‘addiction’ was only used to describe harmful use of substances like nicotine and amphetamines. But more recently, the definition has been expanded to behavioural addictions. Gambling addictions are common, but addictions to exercise, work, and even shopping are now acknowledged.

While there are numerous studies that have found that environmental factors can increase a person’s risk of addiction, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that some of us are more prone to addiction than others, thanks to our genes.

Back in 1996, the US scientist Dr Kenneth Blum coined the term ‘reward deficiency syndrome’, where some people inherit a genetic variation that affects the ‘brain reward cascade’.

While most of us experience dopamine spikes in response to fairly mundane pleasures of everyday life, people with this genetic variation don’t get as much of a hit from these activities, so are more prone to seek ever-greater highs through drugs, alcohol, food and high-adrenaline sports. Blum estimated that up to 30 per cent of the population may have these underactive reward pathways.

While trying to reach a new level in Minecraft might cause your friends to say you’re obsessed, few would question the hours Michael Phelps spent in the pool to achieve Olympic stardom. But even his obsession may have been mediated by the same pathways as less-productive obsessions.

Exercise produces dopamine spikes like other pleasurable activities, and studies of endurance runners have shown that withdrawal symptoms can develop after 24 to 36 hours of not running, producing irritability, anxiety and guilt. “Obsession is socially constrained,” points out psychiatrist Prof Dean McKay.

One determinant of whether your obsession is healthy depends on how valued the obsession is. “Someone could be obsessed with stamps in a way that’s unhelpful. On the other hand, being a philatelist is actually a career where you might look for ways to trade and sell valuable stamps in a collector’s market, the way someone might with art,” he says.

“The other factor is the degree to which the pursuit of an obsession causes personal distress,” says McKay.

Why do we get obsessed with celebrities?

Tabloids and social media have given rise to one of our most common and pervasive obsessions: celebrities.

Obsessions with celebrities are measured using the Celebrity Worship Scale, which was devised by psychologists in 2002 and published in the British Journal Of Psychology.

For most people, relationships with celebrities are what sociologists term ‘entertainment social’, where an attachment to a celebrity provides entertainment or enhances social activities.

They will agree with statements like ‘I love to talk with others who admire my favourite celebrity’.

Mild obsessive qualities can start to come in when these relationships become ‘intense-personal’ (‘When something good happens to my favourite celebrity, I feel like it happened to me’).

An extreme form is called ‘borderline-pathological’ (‘If I was lucky enough to meet my favourite celebrity, and they asked me to do something illegal as a favour, I would probably do it’).

Celebrity worship is fairly new to academia, so not much is known about how these relationships affect our brains.

A 2021 meta-analysis of studies about celebrity worship showed that intense-personal and borderline-pathological celebrity worship are correlated with neuroticism and psychotic tendencies, and appear to be related to poorer mental health.

It is also linked to poor-quality intimate relationships and a difficulty coping with conflicts, though whether intense Taylor Swift fandom or Nickelback devotion causes these difficulties – or stems from them – is yet to be determined…

Read more:

How does obsession become OCD?

In the psychological and mental health realm, obsession is where someone is plagued by intrusive thoughts that they can’t eliminate.

“There is a strong desire not to experience that thought. In a way, it’s the exact opposite of a passion. The person is haunted by their obsession,” says McKay.

When people become so obsessed with a thought that it causes anxiety or compulsions, it can begin to veer into obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

“Let’s say on average, people want to be clean,” says McKay. “If you ask 100 people if they’d prefer their hands to be clean before they eat, the majority of them are going to say yes. And there are going to be some people who really make sure of it, which is still in the range of, shall we say, normal.”

But a few of those people may experience some life stressor, usually something run-of-the-mill and not particularly traumatic.

“Then they’ll push cleanliness to a level where it will start to be harmful, where the washing becomes very excessive, and it leads to problems in other areas of their life,” McKay says. This is where it becomes OCD.

The social factors around taboo topics strongly affect patterns of OCD. “A society may have greater prohibitions about certain behaviours, so you see a corresponding increase in obsessions related to them,” McKay says.

“One that has received a lot of publicity lately is intrusive thoughts about paedophilia. Many people with OCD will have these thoughts – ‘I saw a child, it occurred to me that the child was good looking’. When that thought shows up, the person might say, ‘wait a second, why did I think that? Am I attracted to children?’

“That person is in no way attracted to children – they have no desire, no interest, nothing. But they get that thought, and now suddenly they’re anxious about it.

"Now they’re avoiding that thought and when it shows up they get more anxious, and that makes the thought more prevalent,” he says.

Usually, OCD involves compulsions. Sometimes they’re related to the intrusive thought, like someone who ruminates over germs may wash their hands many times a day.

Read more:

- Why do I get anxious thoughts late at night?

- Dr Michael Mosley: How deep breathing can soothe anxiety, help you sleep and more

Sometimes they’re unrelated, like a child who needs to have his shoes lined up perfectly in order to protect his parents from harm. But in rare cases, OCD can be absent from visible compulsions, and this is where the term ‘Pure O’ arises.

“It’s a useful term because there are taboo thoughts and intrusive ideas that have no clear external ritual that might alleviate them,” McKay says. But psychiatrists don’t tend to use the term, because Pure O sufferers do change their behaviour.

“There are things in the environment that might activate a thought, so sufferers of Pure O might go to great lengths to avoid them.

"For example, they may get this thought: ‘I’m near a steak knife, and I don’t know what might happen’. So they might engage in behaviour where they make sure there are no sharp objects around.”

There isn’t an easily definable behaviour, so it presents like a pure obsession.

Another way people with Pure O act on their intrusive thoughts is to counter them with other thoughts, to seek reassurance.

One common OCD ‘theme’ is sexual orientation obsession, in which sufferers obsess over whether they have a different sexual orientation than the one their current relationship is based on.

If they find someone of the same sex attractive, they might feel compelled to spend time thinking of attractive people of the opposite sex, in order to reassure themselves.

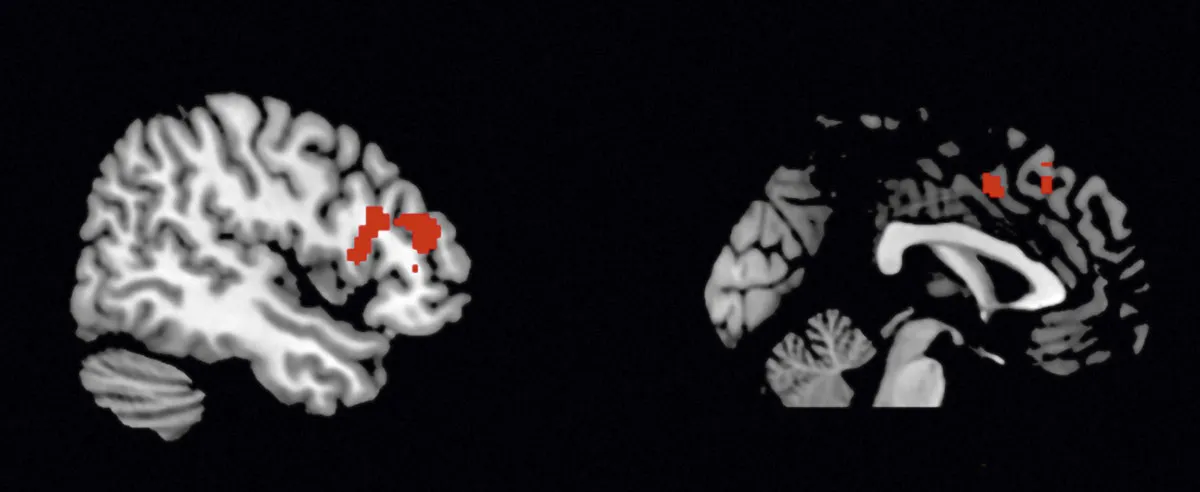

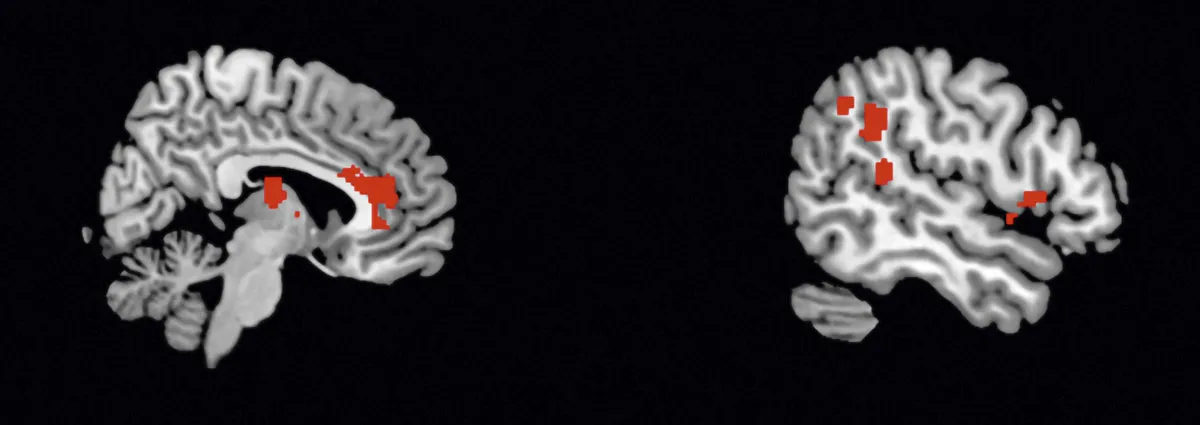

Neurobiological and neuroimaging studies give us some clues as to how OCD plays out in the brain. In functional MRI studies, people with OCD tend to have more activity in the brain’s corticostriatal pathway, which controls movement execution, habit formation and reward.

In rare cases, people develop OCD after head trauma, or in response to infections and encephalitis, adding weight to the idea that changes in the brain can cause OCD.

It’s also expected that serotonin plays a role in OCD, because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are effective for some people who suffer from OCD.

But researchers still don’t have the full picture about OCD. “I don’t think we’ve defined OCD in a way that will permit us to identify the biological base,” says McKay.

“Contamination, for example, stands apart because it’s not just anxiety – it also relates to disgust, which involves an entirely different emotional system.”

Hoarding was also once considered a subtype of OCD, so people with hoarding tendencies may have been included in OCD MRI studies, but recently it’s been removed from the diagnostic criteria for OCD.

Without an accurate picture of what OCD is exactly, it’s hard to get a good idea of what’s happening in the brain.

OCD treatments

So what treatments are on offer for people with OCD? Sufferers may be offered a course of SSRIs, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

In some cases these don’t work, and more invasive treatments like deep brain stimulation are trialled, where electric impulses are passed through electrodes implanted into particular brain areas.

McKay has some tips, if intrusive thoughts begin to recur in our minds. “Remind yourself that a thought is just a thought, it doesn’t necessarily mean anything,” he says.

Psychiatrists talk to their patients about ‘the over-importance of thoughts’, which is an attitude where people assume that if they thought something, it must be meaningful. “But the truth is that people just have random thoughts,” says McKay.

He also suggests keeping in mind that we will always live our lives with some measure of uncertainty. Whether you obsess about making sure your hands are clean, or about proving a complicated mathematical theory, we can only be mostly certain.

“The more that people get comfortable with that, the more likely they are to free themselves from harmful obsessions.”

About our experts

Prof Dean McKay is a psychiatrist and professor of psychology at Fordham University, New York, US. He is head of the Compulsive, Obsessive, and Anxiety Program (COAP) lab and researches the cognitive processes underpinning OCD.

Prof Lennard Davis teaches English at the University of Illinois Chicago, US. He is also professor of disability and human development at the university’s school of applied health sciences.

Read more: