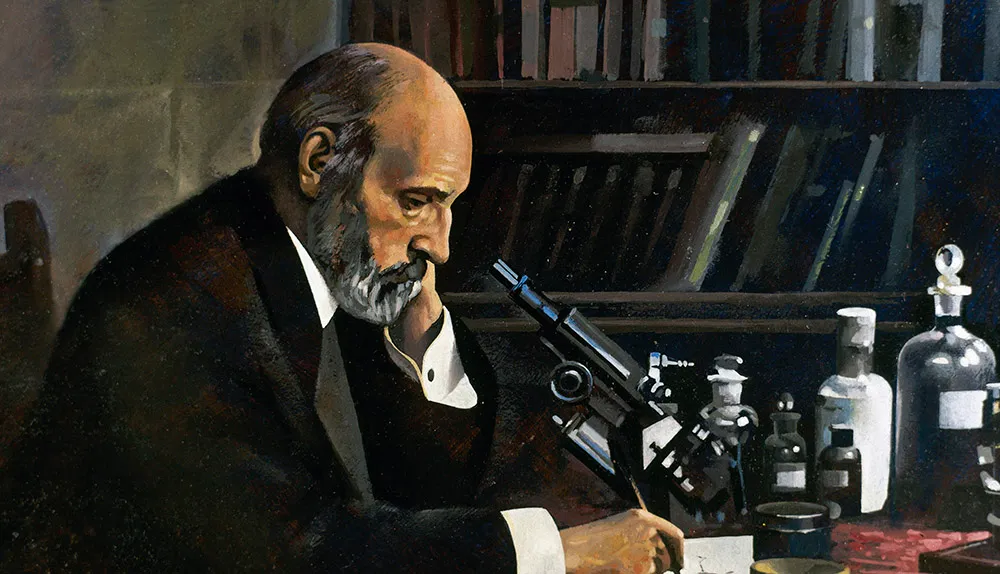

The jelly-like matter of the brain fascinated Spanish pathologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal. In 1877, he saved up all the money he had earned as a medical officer in the Spanish army to buy an old microscope.

For several years he attempted to use the microscope to study and catalogue the tiny structures within the brain, but they were impossible to see clearly.

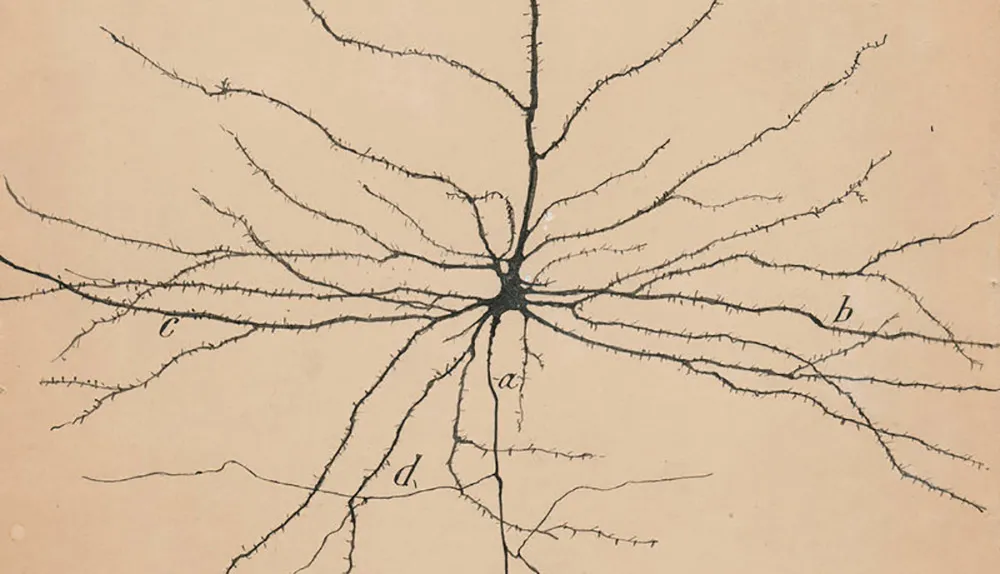

He wanted to solve the fierce, ongoing debate as to whether the brain was made up of individual cells, or whether these cells were all continuously interconnected.

In 1873, the Italian physician, Camillo Golgi, developed a staining technique using silver nitrate that allowed a much clearer view of brain tissue. For years, Cajal worked on refining this technique.

As a passionate artist, he drew everything he saw, and in 1889, he presented his findings to the Congress of the German Anatomical Society at the University of Berlin.

Each stained brain cell stood out perfectly. Its complexity could be seen in detail, showing there was no direct physical connection between each cell, and settling the long-running debate.

Cajal’s pictures are still used in neuroscience today to demonstrate the precise architecture of the brain that underlies memory, and all other aspects of human thought.

Read more about memory and the brain:

- This article first appeared in issue 314 of BBC Focus magazine