Modern medicine, for allits wonders, has a rather large blind spot. Though scientific breakthroughs and new miracle treatments are announced on a seemingly daily basis, doctors know that even the most effective drugs in their arsenal won’t work for large sections of the population.

For example, the drugs commonly prescribed to treat disorders like depression, asthma and diabetes are ineffective for around 30-40 per cent of people they are prescribed to. With hard to treat diseases like arthritis, Alzheimer’s and cancer, the proportion of the population who see no benefit from a particular treatment rises to 50-75 per cent.

The problem stems from how treatments are developed. Traditionally, a drug is approved for use if it works for a good number of people with similar symptomsin a drug trial – and questions are not asked about those in the study who did not respond to the treatment. When the drug is then released and prescribed to the populationen masse, unsurprisingly there are plentyof people – like those in the trial – whodiscover that the latest ‘miracle cure’ isn’t all that miraculous for them.

This ‘one size fits all’ system of drug discovery – though it helped uncover the most important medicines of the 20th Century – is now increasingly seen as ineffective, outdated and dangerous. It means medicines are developed to work on ‘the average person’, when in fact all of us – even our diseases and our responses to drugs – are unique. Not only are many drugs ineffective for large subsections of the population, but they can also cause severe adverse reactions in others.

Thankfully, a completely new approachto medicine is gaining ground. As we learn more about how people differ genetically, medical professionals are tailoring healthcare advice and medical treatment to individuals, rather than populations.

The personal touch

Personalised medicine (sometimes knownas ‘precision medicine’) uses a patient’s genetic data, and other data about their health at the molecular level, to work outthe best treatment for that individual person and others with a similar genetic profile.

We tend to think of our genes as determining things such as our height, eye-colour, or whether we have a genetic disorder. But the combination of geneswe are born with affects our development and health in many subtle ways over the course of our lives. The likelihood of us getting certain diseases as we age, the way we metabolise food, and our reaction to certain drugs are all influenced by the genes we have.

Given what we now know about genes, taking this approach may seem somewhat obvious. But it has only been made possible in the last decade, thanks to the incredible progress that has been made in DNA sequencing technology.

When the human genome was first decoded in 2003, it took over a decade of international collaborative efforts and cost $3bn. Just 15 years later, sequencing a person’s genome takes hours rather than years, and can be done for under $1,000. This means genetic information is more readily available to doctors and researchers developing treatments than ever before.

The area where the new personalised approach to medicine has had the greatest impact, so far, is in oncology, or cancer treatment. The treatment of lung cancer, especially, is seen as a great success story of precision medicine.

War on cancer

For years, doctors were puzzled as to why only around 10 per cent of lung cancer patients responded to a common cancer drug known as TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitors) that halts a tumour’s growth. In the late 2000s, when researchers were able to look at the DNA of patients’ tumours, they found the drug actually only worked in people whose cancer cells had one particular mutation in a gene known as EGFR. The mutation causes cells to grow uncontrollably, and TKI blocks this effect, shrinking the tumour. But in patients whose tumours have different genetic origins, a course of treatment with TKI will result in a barrage of nasty side-effects with no chance of success.

Eventually, the different genes at the heart of different lung cancers were revealed, and the entire process for diagnosing lung cancer changed. Cancers are no longer simply classified by where they grow and what they look like under the microscope. Instead they are tested for gene mutations, and treatment options are chosen accordingly. Even when tumours mutate during treatment and develop resistance to gene-specific drugs, doctors can track the genetic change and pick another target.

Even more sophisticated personalised cancer treatments are on the horizon, such as immunotherapy, which takes a patient’s own immune cells and reprograms them to attack cancer cells. The immune cells, known as CAR T-cells, are extracted from the patient and genetically modified in the lab so they recognise the exact molecular markers growing on the patient’s cancer cells, then injected back in the body to attack the tumour. The USA’s Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved a form of this treatment in August following impressive results in clinical trials.

Personalised medicine is also making an important contribution to the safety of drugs. Suffering a serious adverse reaction to a medicine may seem rare, but is, incredibly, the fourth leading cause of death in North America, and accounts for as many as 7 per cent of all hospital admissions. Again, the problem is caused by our tendency to try and treat large groups of very different people in the same way.

A simple genetic test can flag the key genes that make some people hypersensitive to certain medicines, or if someone metabolises drugs so quickly that they need a higher dose. This approach, known as pharmacogenomics, is still far from commonplace in hospitals and GP surgeries, but new software is in development that will help doctors make prescribing and dosage decisions based on a patient’s specific genetic profile. We could one day even see pharmacists checking your genes in-store before handing over your medicines.

Data-driven

Personalised medicine is not just about genetics. The medicine of the future will be driven by the generation and interpretation of many types of molecular-level data about individuals, captured with a level of precision never possible before.

“We now have technology that can tell us about your genome, your proteomic profile [protein levels], your metabolic profile and your individual microbiome, in detail, at a cost that is increasingly affordable,” says Prof Pieter Cullis, a biochemist at the University of British Columbia and author of several books on personalised medicine.

“Gene analysis is informative, but your genes don’t change over time and so they can’t tell you if you actually have a particular disease or if your treatment is working. Proteins or metabolites inyour blood give us a real-time picture of what your body is trending towards, or whether the drugs you have been given are doing what they are supposed to,” he adds.

From a simple blood sample, scientists can detect the first chemical clues of a huge range of common diseases – known as ‘biomarkers’ – long before any physical symptoms become apparent. In pancreatic cancer, for example, many patients are only diagnosed when symptoms start to show and the disease is gravely advanced. But the cancer may in fact have been growing asymptomatically for up to 15 years, releasing telltale biomarkers that could be detected with molecular tests.

According to Cullis, a combination of powerful computing, vast databases of genetic and biomedical data, and a greater number of skilled geneticists working in healthcare settings, has the power to truly revolutionise medicine. “We are going to move from sickness-based healthcare to preventative measures,” he says, “catching these diseases before they happen or while they are still at an early stage.”

Dr Elaine Mardis, a professor of genomics and personalised medicine expert at the Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio, calls this approach “precision prevention”.

“It’s about more regular monitoring and screening for people with high susceptibility to certain diseases. In its most extreme case, people have been found to have disorders that increase their DNA mutation rate or cause defective DNA repair mechanisms, making them likely to develop multiple cancers over their lifetime. They are then placed on a therapy that can hold off the first instance of cancer,” Mardis says.

Similar treatments known as ‘cancer vaccines’ – tailor-made treatments that help people develop ‘immunity’ to their particular cancer – are currently in development for a range of different diseases including kidney, oral and ovarian cancers. “That, to me, is precision oncology at its finest,” says Mardis.

Beyond cancer

Personalised medicine is starting to have an impact in many other areas of disease too. Last year, researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute revealed that the most common and dangerous form of leukaemia is actually 11 distinct diseases that each respond very differently to treatment.

In HIV and hepatitis C patients, genomic data taken from both the patient and their viruses can help doctors decide on a drug combination that targets the specific strain of the disease and is less likely to cause side effects in that person. This is important because unpleasant side effects can cause some patients to stop taking their medicines. In Canada, this two-pronged approach reduced death rates from HIV by as much as 90 per cent.

And in Alzheimer’s – a disease that is notoriously difficult to treat – genetic analysis is revealing subtypes of the disease that are more likely to respond to certain treatments. Plus, doctors can initiate treatment earlier thanks to the subtle chemical clues that confirm the disease before symptoms are obvious.

But despite all this exciting research, and some remarkable successes, the fact remains that few patients entering the healthcare system in the UK will have access to the specialist biomolecular analysis required to personalise their treatment. Outside of oncology departments, large health systems like the NHS are not set up to gather and analyse biomolecular data for every patient yet. Personalised medicine is too often used as a last resort, or for the lucky few patients selected for clinical trials. The proportion of the population who have had their genome sequenced is tiny.

This is starting to change, however. In the UK, the 100,000 Genomes Project has begun sequencing genomes from around 70,000 people with cancer or a rare disease, plus their families, and last year the NHS published its Personalised Medicine Strategy to help drive the adoption of precision approaches in more areas of the health service.

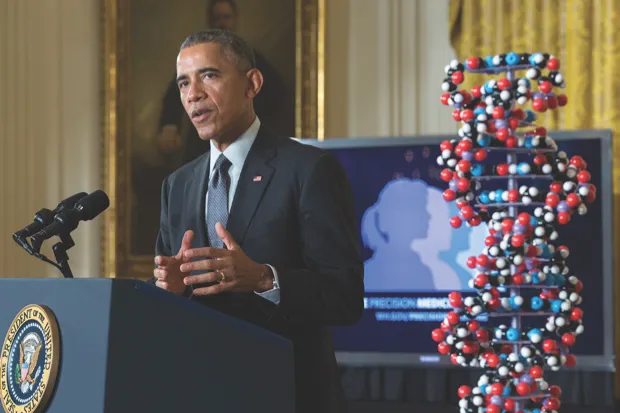

In the US, the world’s largest precision medicine data drive was announced by Barack Obama in 2015. It aims to enrol and sequence genetic data from one million volunteers by 2020. According to Cullis, around 40 per cent of drugs approved inthe US last year were ‘personalised’ in some way – meaning the treatment comes with a ‘companion genetic test’ to ensure it is precisely targeted. “In cancer the shift is already happening… companies will genome sequence a tumour and decide the best treatment for you,” says Cullis.

Doctor, doctor

However, adopting personalised medicine across all areas of healthcare will require major reforms in how services are staffed and structured.

“A large emphasis of personalised medicine is on preventative medicine and treatment, and healthcare systems have never paid for that before,” says Cullis. “It will be a huge shift and will require a lot of people who are not just doctors but trained in biomolecular analysis. The initial users of this will be people who can afford to pay for it themselves.”

In the next few decades, Cullis foresees that visits to the doctor could be replaced by frequent updates from ‘molecular counsellors’, who track your health levels via regular analysis of the biomarkers in your blood, suggesting treatments that are right for your genes. This could be done virtually, with patients uploading their own blood samples to the internet for analysis, and consultation by Skype.

“Molecular analysis will be so disruptive to doctors,” says Cullis. “It will take over the diagnostic and prescription process. The doctor will become your health coach, a person whose job it is to keep you healthy and look out for signs that you need to perhaps go for a hike more often, or change your diet.”

So is it time to get your genome sequenced? Perhaps not just yet.

“Right now it’s about $1,000 to have your genome sequenced, or about $2,000 with the accompanying analysis,” says Cullis. “I had mine done and I didn’t find it all that useful. It told me I was likely to be susceptible to infections when I’m young – but I’m not young any more.”

However, as the infrastructure in healthcare systems becomes centred around bioinformatics and genetic medicine, it seems inevitable that

the medicine of the future will be based around your genes.

“Genome sequencing is getting cheaper all the time,” says Cullis, “and you only need to do it once. When the systems are in place, it will provide important information about you every time you see a doctor, for the rest of your life.”

This is an extract from issue 315 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

[This article was first published in November 2017]

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard