Back in the Victorian era, surgery was as much a spectator sport as a medical procedure, one that some would consider bloodier and more gruesome than the battles fought in the Coliseum of Rome. Were it not for the English surgeon Joseph Lister, and his pioneering work in antiseptics, they might still be the stuff of horror.

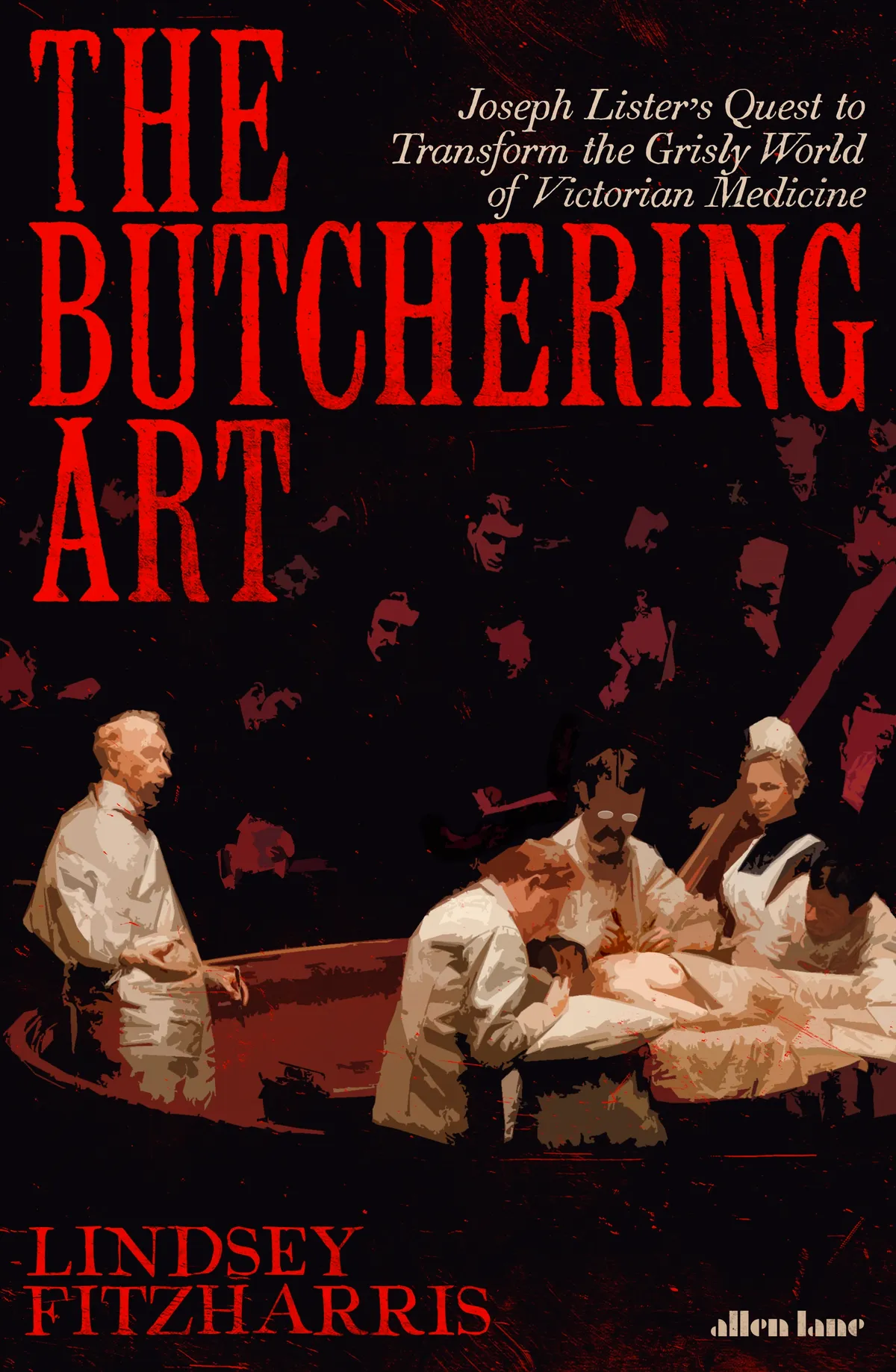

We spoke to American author Lindsey Fitzharris about her book The Butchering Art, now shortlisted for the 2018 Wellcome Book Prize, which explores why Victorian operating theatres were known as ‘gateways of death’, how the shy but brilliant surgeon Joseph Lister discovered what was making them so dangerous, and how it would change surgery forever.

It's not long into the book before you read about the grim realities of Victorian surgery - what would it have been like to undergo the knife back then?

Victorian operating theatres were filled to the rafters with medical students and ticketed spectators, many of whom had dragged in with them the dirt and grime of everyday life. The surgeon wore a blood-encrusted apron, rarely washed his hands or his instruments, and carried with him the unmistakable smell of rotting flesh, which those in the profession cheerfully referred to as ‘good old hospital stink.’

Before the advent of anaesthesia in the 1840s, patients were fully conscious during an operation. Postoperative infection was so common that most surgeries became slow-moving executions.

The book is centered around the story of Joseph Lister - what is it that he did and how did it change Victorian medicine?

You wouldn’t know it from the title, but The Butchering Art is a love story. It is the uniting of science and medicine for the first time in history. Joseph Lister applied a scientific principle (germ theory) to medical practice through the development of antisepsis. In the process, he saved thousands of lives in his own time, and continues to save lives today as we now operate with the knowledge that germs exist.

And yet, most people are only vaguely familiar with Lister’s name through a product he did not even invent: Listerine. In fact, it was not even a mouthwash in the 19th century. It was more commonly used to cure gonorrhea!

He must have been a pretty controversial at the time - was his work quickly accepted in the medical community, or did it face stiff opposition?

Lister faced enormous backlash from the medical community when he announced his antiseptic methods. There was an American surgeon named Samuel Gross who prided himself on not adhering to germ theory. He would walk into an operating theatre, slam the door, and proclaim: ‘There! Mister Lister’s germs can’t get in now!’

Surgeons simply could not accept that tiny, invisible creatures (germs) were killing their patients. It took many decades, and a new generation of surgeons, to shift the paradigm.

Our understanding of medicine has come a long way since Lister and the Victorian doctors - do you think his work in antiseptic surgery is the most significant advance in medical history?

I think Lister’s application of germ theory to medical practice certainly ranks amongst one of the most important advancements in medicine. Without an understanding of germs, it’s unlikely we would be able to do the complex procedures we are able to do today.

To us, Victorian surgery seems barbaric, but do you think in 150 years there will be another Lindsey Fitzharris looking back at our modern surgery with similar disgust?

Absolutely! I hope that when people read The Butchering Art, they realise that what we know today is not what we will necessarily know tomorrow. What will people say about us in the future?

Like the book, your YouTube channel, Under the Knife, is also pretty grisly - what got you into this macabre field of study?

Although I’m a historian by training, I’m a storyteller first and foremost. I often tell the stories about the past that excited me when I was younger. I was a strange child, and I’m an even stranger adult!

That said, I don’t think I could write about Victorian surgery without it getting a bit gruesome. I would be doing a disservice to the patients who submitted to the knife in the 19th century if I romanticized their experiences. After all, it was their bodies that helped advance medicine, and we owe a huge debt to them.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook,InstagramandFlipboard