Have you ever been driving along a motorway, listening to the radio, when your brain suddenly piped up with, “Hey, what if I just turn into the central reservation?” Or perhaps you picked up a knife to slice some bread and wondered, “What if I was to hurt someone with this?”

These are examples of intrusive thoughts – just thoughts that pop into your head, either of their own accord or maybe because of the situation you’re in, such as driving a car or slicing bread. Ideally, we acknowledge these thoughts before simply setting them aside and moving on with our days. But for some people, at certain points in their lives, dismissing intrusive thoughts can become more difficult.

Here, with some help from the experts, we explain what intrusive thoughts are, what happens when they get out of hand and how to deal with them…

What are intrusive thoughts?

From the broadest perspective, an intrusive thought is anything random that “pops into mind”, says clinical psychologist Prof Mark Freeston, who specialises in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and anxiety disorders at Newcastle University in the UK.

Technically, an intrusive thought could be positive, but it’s more often than not the negative ones that we notice. An example might be a sudden panic that you’ve left the oven on and your home is going to burn down. The sort of thing that we all think about from time to time. We might not think of it as ‘unwanted’, because it’s just a thought that we quickly forget about.

Then there are the intrusive thoughts that are very much unwanted, in mental health complaints such as OCD, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and social anxiety. “In social anxiety, the intrusive thoughts would likely be ‘How are other people seeing me?’, ‘Is my hand shaking?’” says Freeston. Whereas, in OCD, the thoughts may be fears of contamination, or in PTSD, they may be memories or flashbacks of a traumatic event.

In psychology, what marks out an intrusive thought as different to a worry or other type of thought is that it’s at odds with what you generally believe to be true, or your values. Psychologists refer to this as an ‘egodystonic’ thought.

Worries are considered more ‘egosyntonic’, meaning they’re more aligned with our beliefs. For instance, if you have been reading about the rising costs of energy and supermarket essentials, and are starting to spend more than you earn, you might understandably be concerned about how you’re going to pay your bills, but that would be a worry – not an intrusive thought.

Are intrusive thoughts normal?

Yes, although we didn’t always realise this. Psychologist Prof Jack Rachman was the first to show experimentally that intrusive thoughts are ‘normal’. In the 1970s, he and colleague Padmal de Silva surveyed 124 people with no known psychiatric conditions and found that nearly 80 per cent of them often had thoughts that would be classed as intrusive.

They compared the content of these thoughts to those of people being treated for obsessions. Surprisingly, when the intrusive thoughts experienced by both groups were written down, a panel of psychologists found it difficult to work out which group a lot of them belonged to. There were differences though. In clinical patients, intrusive thoughts tended to crop up more often; they were also more intense and harder to dismiss.

While Rachman’s study profoundly influenced the next half a century of research on intrusive thoughts, the data on which it was based was from a relatively small group of UK students. Researchers carried out similar surveys over the years, but they were still limited to Europe and the US.

Then, in 2014, a multinational team of researchers looked further afield, studying intrusive thoughts in 777 people across 13 countries and six continents. The team interviewed each person to check that they were really having intrusive thoughts as opposed to worries or other types of thoughts. The results suggested that 94 per cent had had at least one intrusive thought in the previous three months.

Today, Prof Adam Radomsky, the lead author of the 2014 study, who is based at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada, says he believes we all have intrusive thoughts. “We know that people are more likely to notice them or struggle with them during stressful periods,” he says. “But I think it’s just a fact of humanity that we have them. Most of them we probably don’t notice.”

Perhaps the fact that we do have them is the result of important processes going on in our brains – if we never had random thoughts or considered things that we didn’t believe to be true, how would we create abstract art or dream up fantastical fictions?

Freeston agrees that intrusive thoughts are “part of the human condition”, adding that it’s beneficial for humans to have random thoughts popping up all the time. “One of the arguments that has been put forward is that if we didn’t have random thoughts, we would never solve problems,” he says.

In OCD, the relationship between intrusive thinking and creativity has been explored as a way of confronting the condition head-on. For instance, writing down random thoughts could be a way to harness them instead of allowing them to block up our brains.

Read more about OCD:

How will I know if my intrusive thoughts are a problem?

It’s how you respond to the intrusive thoughts that tends to determine whether they’re problematic. “Someone could have a thought about some bizarre, evil thing happening,” says Freeston. “If you were Stephen King you’d say, ‘That’s a great idea.’ And then write a novel. But if you think, ‘What sort of a person has this bizarre thought?’ or ‘It might mean that I’m this awful person that I think I am’, from there, an intrusive thought could become an obsession.”

Obsessions in the clinical sense are intrusive thoughts that are unwanted and repeated often. These can develop in OCD, particularly in OCD that occurs during pregnancy or after childbirth. But repeated, unwanted thoughts are also characteristic of a raft of other mental health conditions, from PTSD and eating disorders to schizophrenia. Intrusive thoughts can also be related to physical health problems. Cancer patients, for example, can suffer intrusive thoughts about their cancer returning that may impinge on their physical recovery.

In people who develop obsessions or more distressing intrusive thoughts, the thoughts begin to occur more regularly when they try too hard to get rid of them, instead of just accepting and ignoring them. In some cases, people progress to carrying out physical actions to try to deal with the thoughts, such as tapping, counting or repeatedly checking that they’ve performed a particular task. These are compulsions.

If you’re going through a particularly busy or stressful period and noticing yourself struggling with intrusive thoughts more than normal, this doesn’t necessarily mean you’re developing OCD. It just means you need to be more mindful and perhaps do things to help you reduce the stress. Radomsky suggests “not necessarily pushing the thought out or avoiding it, but focusing on the things that matter,” along with some self-care, which might be as simple as sleeping and eating well.

On the other hand, intrusive thoughts that come out of the blue need to be taken seriously. Abrupt onset of OCD symptoms in children might be the result of a bacterial or viral infection, as in Paediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections (PANDAS).

First described in the 1990s by child psychiatrist Dr Susan Swedo, PANDAS is rare, so can still be thought of as a controversial diagnosis, according to Alison Maclaine, whose 12-year-old son Jack developed PANDAS over four years ago. Jack now struggles to leave his room due to intrusive thoughts about dying and running away. “The intrusive thoughts were one of the first symptoms of his illness and have consistently been the cause of most distress,” Maclaine says. “For the last five months, he has been unable to attend school.”

Jack’s intrusive thoughts were initially put down to autistic spectrum disorder and anxiety. Eventually, he was treated with anti-inflammatories and antibiotics, which helped, but Maclaine wonders how different life would be now if they had received the correct diagnosis straight away. (Other symptoms that may indicate PANDAS are tics, hyperactivity, problems sleeping, and panic or rage attacks.)

What causes the intrusive thoughts?

Remember, intrusive thoughts are normal. If we accept that they’re just random thoughts, then what causes them is simply the constant bubbling-up of ideas and memories in our busy brains. According to Radomsky, there is sometimes a trigger for such thoughts – seeing a fire extinguisher, for example, and then finding yourself wanting to rush home and check that the house hasn’t burned down. But sometimes they really are random; just the result of our minds being ‘noisy’.

What about those people whose intrusive thoughts bother them, though? Do their brains work differently? Perhaps they do. In 2020, Portuguese researchers reviewed evidence collected over the last decade concerning people with OCD and how they regulate their thinking – what happens, for example, when they’re asked to focus on unpleasant mental images or real pictures. The researchers found that in brain scans, people with OCD show “altered brain responses” across several areas of their brains compared to healthy volunteers.

This brain imaging may just be illuminating what psychologists describe as someone trying to push away their thoughts. For his part, Randomsky doesn’t favour neurobiological explanations for why people struggle with intrusive thoughts, because he doesn’t believe they’re helpful when it comes to treating them. “There’s very little we can do to change the brain directly,” he says. “But we do have complete control over what we choose to think and what we choose to do, so there’s a lot more potential to talk about the mind and behaviour instead of talking about the neurobiology.”

By talking to people, psychologists can sometimes identify reasons why individuals might be sensitive to the content of certain intrusive thoughts – perhaps as a child they witnessed a fire or a violent attack. Later in life, there are times when we’re all supersensitive to certain thoughts and, hence, we’re more likely to take notice of them. After becoming a parent, for instance, we might be hyperaware of safety issues.

But although we might think of these sensitivities as ‘causes’, rather than any structural or chemical differences in the brain, whether someone develops OCD is partly just down to bad luck, according to Freeston. “Potentially there has been a series of times when you’ve been particularly vulnerable and you’ve had a thought and you’ve appraised it in a particular way,” he says.

“So ultimately, the reason why you got OCD is none of these initial causes. It’s this combination that means that you ended up appraising the thought in a particular way, acting on that and then strengthening your system of appraisals and behaviours over time.”

What if my intrusive thoughts are real?

Remember that intrusive thoughts tend to be at odds with people’s actual beliefs or values. So a person with an eating disorder may have intrusive thoughts about being overweight, even if they can agree, when looking at a number on a scale, that they’re not.

By the same token, a person with OCD may have intrusive thoughts about something bad happening because they’ve been contaminated by germs or particular items aren’t ordered in a certain way. And those thoughts may still bubble up even if that person can rationally say that nothing bad is likely to happen.

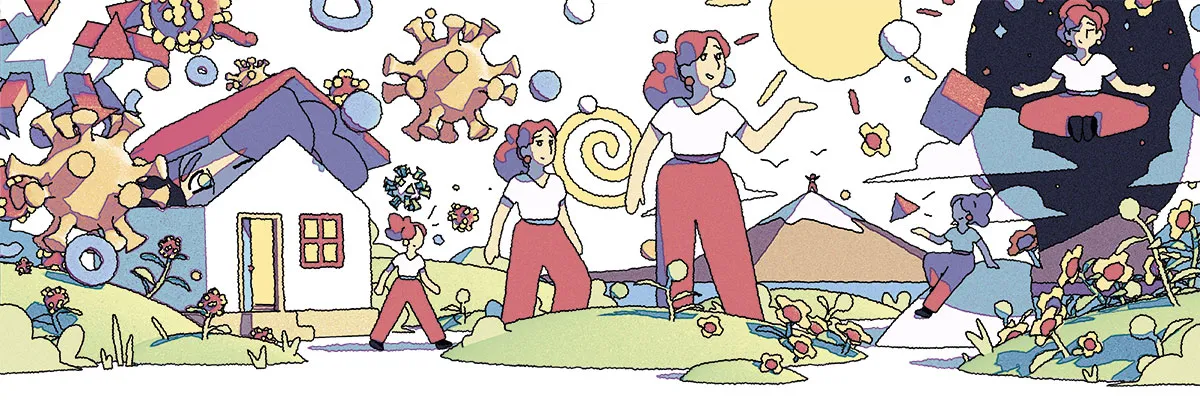

Sometimes, however, real-life events occur that can confuse matters. Such as when a pandemic breaks out, for example. Disease outbreaks are known to temporarily increase intrusive thoughts about illness, and in the world we’ve lived in since 2020, contamination of every available surface and air space is a legitimate concern.

So if you have intrusive thoughts about virus-contaminated surfaces or catching COVID, is it something to be concerned about? Prof Meredith Coles, director of the Binghamton Anxiety Clinic at Binghamton University, New York, ponders the question.

“In some respects, I could argue that your anxiety should have been elevated in the last year or two – that you should have been having more intrusive thoughts,” she says, adding that a bit of anxiety may not be a bad thing if it motivates you to get vaccinated. “Does that mean you have OCD? Or does that mean you’re human and you’re going through a pandemic?”

We’ve certainly all been through a difficult time. But what about those of us who are already suffering from OCD? Could COVID exacerbate the condition? One Italian study published in 2021 suggested that it could.

For the study, 742 people completed questionnaires and the respondents who scored highly on washing and contamination questions normally used in OCD diagnosis tended to perceive COVID as more dangerous. However, a high score for health anxiety (previously referred to as hypochondria) was more strongly associated with concern about COVID.

Coles reckons that as we pass the peak of the pandemic, we should see any rise in intrusive thoughts receding. We’re more resilient than we sometimes believe, she says. Though she does advise doing things to stay on top of our anxieties, such as seeking support from friends and family, and turning off the news once in a while.

How can I stop my intrusive thoughts?

Again, intrusive thoughts are normal, so you can’t stop them. But if intrusive thoughts are troubling you, then well-established treatments are available. For OCD (and body dysmorphic disorder), this is usually cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and exposure and response therapy, although there are separate, tailored CBT approaches for other disorders like PTSD.

CBT focuses on helping you to change the way you think, including how you react to intrusive thoughts. Exposure and response therapy challenges you to confront the object of your fear, so if you have cleaning compulsions, it might involve touching the taps in a public toilet without carrying out ritual cleaning.

Although these treatments don’t benefit everyone to the same degree, what benefit they do offer is backed up by strong evidence. There are also other new approaches, like mindfulness and compassion-focused therapy (which encourages patients to develop a more self-supportive inner voice), but they don’t yet have the data behind them.

“There’s evidence that [they] work better than nothing, but there are very few direct comparisons,” Freeston says, referring to how they compare with the standard approaches.

Developing new treatments also involves learning more about what causes intrusive thoughts. Coles is currently working on the relationship between sleep disturbances and intrusive thoughts in OCD. “People with OCD tend to stay up really late,” she says, “It’s just initial data, but this seems to potentially be related to not being able to get the thoughts out of your head.”

Radomsky’s group is working on helping people to change certain beliefs that might be related to their intrusive thoughts. For instance, the belief that their memory might not be very good; correcting that can help people get on top of repetitive checking behaviours. Another focus is beliefs about losing control. “People believe sometimes that if they lose control of their thoughts, they might lose control of their behaviour,” he says. “Those beliefs in OCD are inevitably false.”

For anyone who feels that intrusive thoughts may be becoming a problem, he recommends The Anxious Thoughts Workbook by David A Clark.

- This article first appeared inissue 378ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here

Read more about mental health: