“I am a brain, Watson,” Sherlock Holmes told his assistant. “The rest of me is mere appendix.”

While most of us don’t operate on quite the same level as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional super-sleuth, it’s true that everything we know about the world – and ourselves – is contained within our brains, to which our bodies are, if not necessarily appendices, then certainly largely subject to.

Our brains control our thoughts and actions, and are unique to each of us. Boasting 86 billion neurons and 100 trillion connections, they’re so complex that it’s almost impossible for us to get our heads around them, so to speak.

But let’s try…

What are the different parts of the brain?

1. Cerebrum

Encompassing most of the wrinkly structure we recognise as the brain, the cerebrum is divided into two hemispheres (left and right) and four regions, or lobes.

2. Frontal lobe

A large section behind your forehead with a wide variety of responsibilities, ranging from movement and behaviour to language and emotions.

2.1. Primary motor cortex

This is a bunch of nerves found in the dorsal section of the frontal lobe that control voluntary movements.

2.2. Supplementary motor cortex

Also part of the frontal lobe, the supplementary motor cortex is involved in the planning of your movements.

3. Occipital lobe

Heavily involved in vision – damage to this lobe can cause problems with reading, writing and colour perception.

4. Parietal lobe

Crucial to interpreting the outside world, the parietal lobe processes sensory and spatial information.

4.1. Somatosensory cortex

Part of the parietal lobe, this is a central destination for sensory info collected all over the body.

5. Temporal lobe

Involved in hearing and memory, the temporal lobe helps us remember music, for example, and understand language.

5.1. Hippocampus

A curved part of the limbic system (the ‘primitive’ brain) associated with memory and decision-making.

6. Thalamus

Filters sensory and movement information that is passing between the body and brain.

7. Cerebellum

Densely packed with neurons, the cerebellum is important in movement and balance.

8. Amygdala

An almond-shaped component of the limbic system with roles in stress, emotions and memory.

How does the brain work?

The brain is often thought of as a biological computer: a very efficient one that can handle a tremendous amount of work at much lower power than your average laptop. But neuroscientists don’t like this analogy, and it’s unhelpful for understanding how the brain works, since most of us don’t understand how computers work either.

Instead, we might consider what neurons – key components of our brains – do to allow us to think, move and sense.

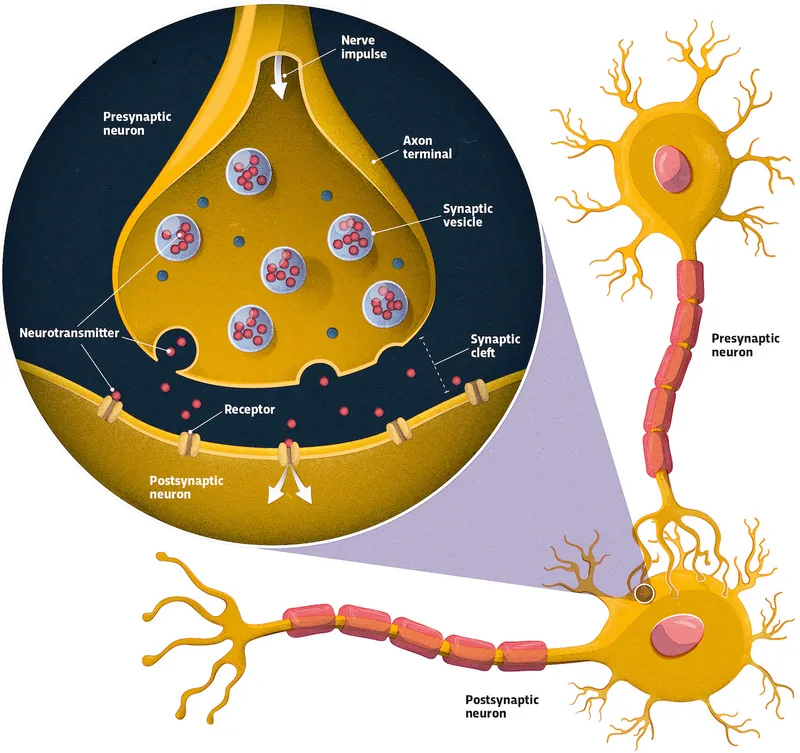

Neurons, like other nerve cells, are tree-structured carriers of signals that speed along the neurons’ trunks, from branches to roots, where they’re passed to other neurons by the release of chemicals (neurotransmitters) across the gaps (synapses).

A thought is the result of the signals spreading through networks of neurons. Movements rely on messages being sent from the brain to neural outposts in our muscles, while sensory inputs depend on them travelling the other way.

We know that these pathways have to function for our brains to work, but scientists are still far from understanding the circuitry for memory, pain, emotions, attention and decision-making. Though some of these functions are traditionally tied to specific areas of the brain, recent evidence suggests it’s not that straightforward – the brain’s duties can’t be so neatly divided.

Do we really only use 10 per cent of our brains?

No. It's a myth that we only use 10 per cent of our brains. While it may be true that if you took a snapshot of activity in the human brain, then less than 10 per cent would appear to be firing at any one moment, it’s certainly not the case that 90 per cent of the brain is useless.

That would make no sense since evolution is pretty good at getting rid of bits of the body that don’t make any useful contribution. Hence we no longer have tails, fur or claws.

Experts are more of the mind that we do need all of our brains, just not all of the time. In 2020, UK researchers found that mentally draining tasks divert energy away from other processes and, as the brain has a limited energy supply, this probably puts a cap on the number of tasks it’s capable of carrying out simultaneously.

What can we do to keep our brains in tip-top condition?

Some decline in brain functioning is inevitable as we get older. But with age also comes an increased risk of certain neurological conditions, such as dementia and stroke.

Dementia affects around a third of people over the age of 90. While science hasn’t found a way to stop this deterioration, there may be things we can do to slow it down, or at least avoid speeding it up.

Unfortunately, current research suggests it requires more effort than simply eating oily fish twice a week. Earlier this year, a 10-year-long study of more than 29,000 adults over the age of 60 showed that maintaining a healthy lifestyle can slow memory decline – even in people with genetic factors that make them more susceptible to dementia.

But for those who took part, a ‘healthy’ lifestyle meant keeping on top of a whole range of factors, from diet and exercise to social activities and brain-stimulating activities such as reading and writing.

How do our brains compare to those of our ancestors?

Remains of Australopithecus afarensis – ape-like animals related to the famous ‘Lucy’ skeleton discovered in 1974 in Ethiopia – suggest that our three-million-year-old ancestors’ brains were about a third of the size of ours.

But Lucy’s relatives were smaller than modern humans.

Even the heavier males of her species only weighed in at around 42kg (93lbs), the average weight of a 12-year-old human. So perhaps a more useful comparison is brain size as a proportion of body weight. While Lucy and her relatives’ brains made up around 1.3 per cent of their total body weight, those of the first Homo species that lived about two million years ago made up closer to 1.7 per cent.

Our own, more advanced brains account for 2.2 per cent of our body weight. However, recent research shows that although A. afarensis brains were organised like those of apes, they took longer to grow, meaning the primates had a longer childhood – just like modern humans.

A brief history of brain science

2000

Brain scans of London taxi drivers suggest the hippocampus (a region involved with spatial memory) expands to accommodate navigational demands. The study shows taxi drivers’ hippocampi are bigger than those of non-taxi drivers and that their size increases with time spent in the job.

2005

A US study links big brains to being smart, claiming to put an end to a centuries-old debate. However, neuroscientists still dispute the connection, arguing that intelligence is more about how our brains are organised than their size.

2010

Brain recordings made by US researchers suggest brain ‘coupling’ occurs between two people when one is listening to the other speak. The harder one person listens, the more closely their brain activity resembles that of the speaker.

2015

Neuroscientists claim they have created false memories in mice by stimulating the reward centres in their brains when they visit a particular location. The implanted memories apparently fool the mice into returning to the same spot again and again.

2020

Researchers unveil a ‘plug-and-play’ device that can be implanted in a paraplegic person’s brain, allowing them to control a cursor on a computer screen using just their thoughts. The device uses AI to match the person’s brain activity to their cursor movements.

Read more:

- Is fish actually ‘brain food’?

- Is there such a thing as left brain vs right brain?

- Here’s why ‘baby brain’ can change a new parent’s mind

To have your mind blown by more science, check out our ultimate fun facts page.