How would you react if someone told you that just taking some pills or having an injection could add 20 years to your life? Not only that, but those extra two decades would be healthy years. You would probably not believe them.

But for the past few decades, research has been taking place to understand exactly what happens when we age and what drives those changes. While the effects of ageing have always been abundantly clear, what’s going on inside our bodies that makes those things happen has not.

Now, a new wave of this research into the science of ageing is taking place not in humans, but in our closest companions – dogs. While studying dogs may not seem the most obvious way to try and understand human ageing, our furry friends can actually give us insights into our biology that we cannot.

Dogs share our homes, so they are exposed to many of the same factors that influence how well we age. But they also age much faster than we do – providing scientists with an accelerated view of the processes. There’s another important factor too. When you put the fur and four legs to one side, dogs and humans are much more alike than you might think.

Read more about dogs:

- Dogs go through a stroppy teenage phase too

- Dogs’ cold noses are 'ultra-sensitive heat detectors'

- Dogs' secret superpower: not intelligence, but love

- Can owning a dog extend your life?

It’s why several large research projects have sprung up in the past few years that are seeking to understand how dogs age – not only to help them, but us too.

One of the most recent additions to the pack is the Dog Aging Project in the US, which since its launch in November 2019 has recruited 80,000 canine participants. The scientists involved with it will soon be picking over the lifestyles and health of these dogs to see what they can uncover.

Some of these pooches will also be taking part in the trial of a drug that is currently given to organ transplant patients. In tests in the lab, on everything from mice to flies, the drug has revealed its ability to extend life. But research in the lab is one thing. If it works on dogs that live in our homes, it would be the best evidence yet that it could do the same for us.

Stop searching for cures and start slowing down ageing

Thinking about medical treatments for ageing itself is a very different approach to how we usually think about our health. “What we have been doing for the past 200 years is trying to cure diseases, which is absolutely the wrong approach to increasing healthy longevity,” says Prof Matt Kaeberlein, an expert in the biology of ageing at the University of Washington and a founder of the Dog Aging Project.

“Curing age-related diseases one at a time, a whack-a-mole approach, is not effective. If you were able to cure cancer, heart disease and kidney disease at the same time with a magic pill, a 50-year-old woman would get about a decade of extra life,” says Kaeberlein, owner of Dobby the German Shepherd (9) and Chloe the Keeshond (14).

“You continue to have other age-related diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, liver disease and lung disease, so the effect on life expectancy is relatively small.” It also means those additional years may not be healthy years.

Much more effective, says Kaeberlein, is to slow down ageing itself. “If you target the molecular mechanisms of ageing, then we can expect more substantial effects on lifespan. But more importantly, those extra years will be in relatively good health,” he says.

A central strand of the Dog Aging Project is to understand how our surroundings, such as the air pollution to which we are exposed, as well as our lifestyles, influence how long we live.

Your dog questions answered:

- Why does my dog go round in circles before she poos?

- How do seizure alert dogs predict seizures?

- Why do many dogs appear to have an innate fear of bangs?

- Why do dogs chase their tails?

Dog owners in the US who are signed up to the project will be asked to complete a 200- to 300-question survey on the health and lifestyle of their pet – everything from what they eat, to what they drink and how much exercise they get. The researchers will also link this with publicly available data about the conditions the dogs are living in, such as the local air quality and the amount of green space near them.

“Dogs share our environment with us and in many ways they are more exposed to it than we are, so they are potentially sentinels for environmental factors shaping ageing,” says Prof Daniel Promislow, an expert in ageing at the University of Washington and a co-founder of the project.

“In normal times, we go to work every day and we might drink our water from a bottle instead of the tap and we don’t tend to stick our noses in the dirt.”

There’s also the fact that dogs age 7 to 10 times faster than humans. “Everything is speeded up in dogs, so if there is something in the environment that creates an increased risk of disease, maybe an endocrine disruptor or something, it might take 30 years to show up in a human, but it might show up in three or four years in a dog,” says Promislow, owner of mixed-breed dog Frisbee (13).

Dogs also get many of the same diseases as we do. “They get cancer, kidney disease and intestinal disease,” says Promislow.

The similarities don’t end there. “When I give talks to people involved in human medicine, I give them a list of the drugs being used to treat anxiety in dogs and they are all the same drugs they are using with their human patients,” says Prof Elinor Karlsson at University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Karlsson is founder and chief scientist of Darwin’s Ark, another dog-ageing research project. As the owner of four cats, Darwin (16), Lacey (4), Hopper (3) and Beagle (3), she hopes to run a similar ageing research project with domestic cats and so provide further opportunities to find out what affects ageing most.

The similarities between human and dog get right down to the level of our DNA. A vast number of regions of the human genome have been found to be similar to the dog genome. That’s important because how long we live and how well we age is under the influence of our genes as well as our environments and our lifestyle. There are tantalising signs that dogs can provide some interesting insights here too.

Back in 2007, a genetic study of 143 dog breeds published in the journal Science showed that about 50 per cent of the variation in dog size is down to a single gene, called IGF1, that’s also found in our cells.

Small breeds, such as the Chihuahua and Pekingese, all have one particular version of the gene, whereas giant breeds, such as Great Danes, have one of two other versions. It came as quite a surprise that a characteristic so varied in dogs is controlled to such an extent by a single gene.

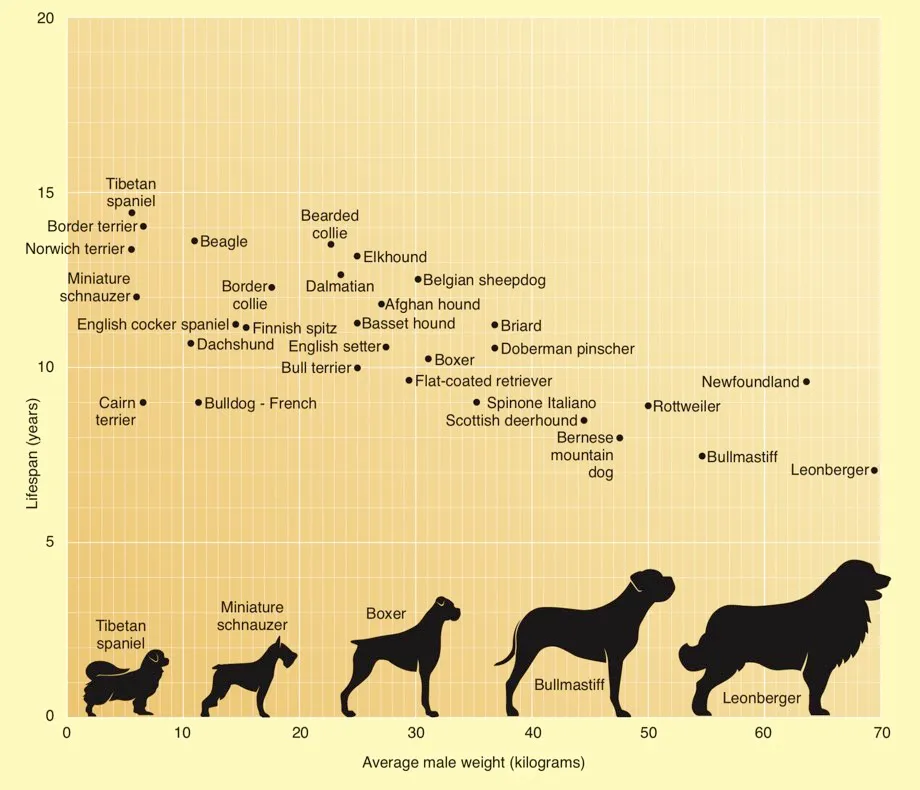

“The other thing that’s interesting is that IGF1 has been associated with lifespan in the lab in mice and flies,” says Promislow. It prompts an intriguing question. Could this gene be a reason why large dog breeds tend to be shorter-lived than smaller ones?

This is something of an oddity given that larger animals, such as elephants, tend to live longer than smaller ones, such as mice. It is a question the Dog Aging Project is looking to answer.

A wolf in dogs' clothing

Domestic dogs, Canis familiaris, started evolving from the Eurasian grey wolf, Canis lupus, around 15,000 years ago, and it’s our selective breeding of them that has made them the most diverse species of mammal on the planet. The Kennel Club in the UK recognises 218 breeds. All those differences provide a great opportunity to study ageing.

“Dogs are the most varied species of mammal in terms of size, coat colour and behaviour, but also the things we don’t see – the diseases they die of and how long they live for,” says Promislow. “So that creates an enormous opportunity to understand the way in which genes and environment shape ageing.”

The dogs within the Dog Aging Project fall into different groups depending on how they will be involved in the research. All of the 80,000 dogs whose owners fill out the health and life experience survey will become part of a ‘project pack’ that will be followed for the rest of their lives to monitor how their health changes and at what age they die.

These dogs live in the US, but the hope is to expand the project internationally. “People love dogs and we are working with dog owners,” says Promislow. “In a great act of altruism, they are sharing their data with us.”

One group of 10,000 dogs in the project pack will also have their whole genomes sequenced, while the owners of a group of 1,000 will be handed kits to give to their vets to collect samples of hair, blood, poo and other things. This group will help researchers understand more about the dog microbiome (which again shows a striking similarity with ours) to explore the role it plays in ageing.

Then there’s trial of the potentially life-extending drug, rapamycin, that will involve 500 dogs. The dogs in the rapamycin trial will have regular check-ups at veterinary teaching hospitals across the US to see what effect it has on them.

“I’m a dog person, I’ve had dogs all my life so I wanted to try something that we were confident could be tested safely,” says Kaeberlein. “Organ transplant patients take rapamycin for decades without significant problems.”

Read more about having pets:

- Four animal 'facts' that are completely wrong

- 6 reasons your domestic cat is wilder than you think

- Which animals are more intelligent – dogs or cats?

Researchers already have some insights into how rapamycin slows ageing. It does it by reducing levels of a protein in the body called mTOR. Reduced mTOR levels increases the rate of autophagy, the process in cells that breaks down damaged molecules and acts as a recycling system.

“There is pretty good evidence that this turning up of autophagy can help break down some of the damage that has occurred in ageing at a molecular level and recycle some of the building blocks into new molecules,” says Kaeberlein.

These damaged molecules that are broken down may include the misfolded and clumped together proteins that have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease. Rapamycin may also help recycle mitochondria, which are the powerhouses inside our cells.

“We know mitochondria are damaged with age and there’s an autophagy process called mitophagy which can break down damaged mitochondria and recycle them into new building blocks.”

The rapamycin trial isn’t the only test of a potentially life-lengthening treatment in dogs. A US business Rejuvenate Bio, founded by high-profile Harvard Medical School geneticist Prof George Church among others, has started pilot testing life-enhancing gene therapy in dogs.

The trial involves injecting American Cavalier King Charles spaniels with a harmless virus that carries genes for proteins found to dial back ageing, by improving things like heart health and kidney function. If all goes well, the trial will be expanded to other dog breeds and then, possibly, human trials can start.

But there’s still the question of our perceptions of research into life extension. Prof David Sinclair, an expert in ageing at Harvard Medical School and author of Lifespan: Why We Age And Why We Don’t Have To thinks the dog research may help change how we think about ageing.

“Most of us dog owners would say our dogs don’t live long enough, although most of us would say humans live a long time,” says Sinclair, owner of a Labrador named Leuka (6), and a crossbreed called Charlie (13).

“But it’s only relative. If two-thirds of humanity lived for 150 years, those who didn’t live beyond 80 would be pitied. I think eventually society will change and realise 80 years is not very long in the grand scheme of the Universe.”

Kaeberlein also thinks the research in dogs will convince people that ageing is now under our control. “This is not science fiction, it’s biology,” says Kaeberlein. “People love their dogs and if we can help people’s dogs live longer by slowing ageing, it might change the way people think about the biology of ageing and recognise it is possible in humans too.”

- This article first appeared in issue 350 of BBC Science Focus - find out how to subscribe here