Few forms of exercise have been as highly and intensely researched – or publicised – in recent years as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). In 2018, HIIT headed up the yearly survey of worldwide fitness trends by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). It has remained in the top five since it entered at the top spot in 2014. HIIT is proving to be an enduring hit.

True, HIIT is down to number three in the ACSM’s 2019 chart, behind wearable tech (number one) and group training (number two). But if you’ve been to a fitness class lately, then there’s a strong chance that you did HIIT, even if you didn’t realise it at the time. “The best way to explain it is repeated bouts of high intensity followed by a bout of recovery,” says Tom Cowan, an exercise physiologist at the Centre for Human Health and Performance (CHHP) on London’s Harley Street.

What is HIIT and what does it do?

According to the ACSM, high-intensity intervals are exercises that you typically perform at 80 to 95 per cent of your maximum heart rate, for anywhere from five seconds to eight minutes. Generally, the shorter the interval, the higher the intensity and vice versa. The work intervals are alternated with periods of complete rest or active recovery performed at 40 to 50 per cent of your maximum heart rate, lasting for the same duration (although they can be longer or even shorter depending on your fitness).

HIIT is highly adaptable for varying fitness levels and goals, which partly explains its popularity among everybody from elite athletes to cardiac rehab patients. It can be performed on gym equipment such as static bikes, treadmills and rowing machines (cardio HIIT), or via exercises such as press-ups (bodyweight HIIT).

Its popularity is welcome news, because HIIT has been shown to improve fitness, cardiovascular health, cholesterol profiles and insulin sensitivity, which helps stabilise blood glucose or sugar levels – of particular significance to diabetics. HIIT also reduces fat – both abdominal and the deep, visceral kind that engulfs your inner organs – while maintaining muscle mass or, in less active individuals, increasing it.

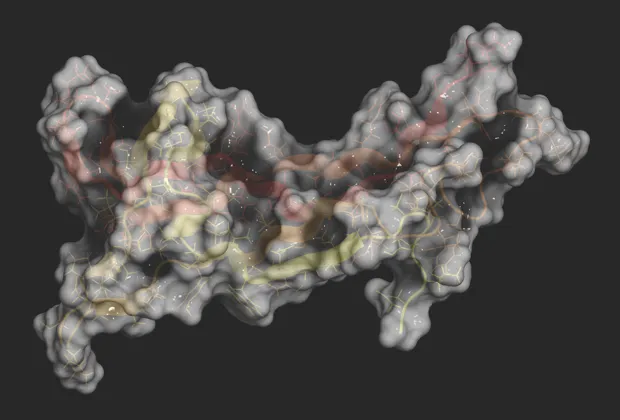

More strikingly, according to a small study in Cell Metabolism in 2017, HIIT effectively halts ageing at the cellular level, by increasing the production of proteins for the mitochondria, your cells’ energy-releasing powerhouses, which otherwise deteriorates over the years. Other forms of exercise such as strength training do likewise, but HIIT is more effective. The study also stated that muscle cells, like those in the brain and heart, wear out and aren’t easily replaced, so if exercise prevents deterioration of mitochondria in muscle cells, or even restores them, then it likely does so in other tissues too.

Similarly, HIIT beats continuous moderate-intensity exercise when it comes to releasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that protects nerve cells. This promotes plasticity (the forming of new connections, which aids learning and memory) and may even help regulate eating, drinking and body weight.

Perhaps HIIT’s biggest selling point is its efficiency: a workout can last up to an hour, but it can also be completed in 20 minutes or less. Tabata, one of the most well-known HIIT protocols, consists of 20 seconds of work followed by 10 seconds of rest, repeated eight times for a total of just four minutes, not counting the warm-up and cool-down.

In a famous 1996 study by Tabata’s namesake Dr Izumi Tabata, people who performed the four-minute protocol on an exercise bike five times a week improved their VO2max – the uppermost rate at which your body can utilise oxygen for energy during exercise – by 15 per cent after six weeks. People who exercised for 60 minutes at moderate intensity five times a week only improved their VO2max by a mere 10 per cent. Moreover, the Tabata group boosted their anaerobic capacity – the body’s ability to produce energy without oxygen, used for short bursts of hard effort – by 28 per cent. The continuous exercise group’s stayed the same.

HIITing the spot

It sounds like the fanciful stuff of home shopping channel infomercials, but HIIT is legit – even The One-Minute Workout, a book published in 2017. The workout (three 20-second intervals interspersed with one to two minutes of recovery) improved the fitness of people who performed it three times a week for 12 weeks, just as much as those who did traditional cardio for 50 minutes three times a week. It was devised by Dr Martin Gibala of Canada’s McMaster University, who is one of the leading researchers into HIIT. “It’s not a fad,” confirms CHHP’s Cowan. “It’s completely got the backing, and there are more and more studies coming out.”

While it might seem like a recent trend, HIIT isn’t a new concept. It’s been employed for at least a century by athletes. For example, legendary Finnish distance runner Paavo Nurmi set a 1,500m world record in 1924 by running repeated hard sprints in training. What is new is the scientific research, which began in earnest at the start of this century.

HIIT has been heralded as a powerful weapon in the fight against unhealthy lifestyle-related diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. And if nothing else, it’s convenient: one of the most-cited obstacles to physical activity is lack of time.

“Also, a lot of cool, fashionable gyms and studios that are all glammed-up with music – not just in London but there are plenty there – follow a HIIT-based approach, with circuit-type or spin classes,” says Cowan. “That’s quite appealing to a lot of people, as opposed to having to jog for an hour in the park, which is a bit more monotonous.”

This variety is what makes HIIT so impactful. “Because you get the rest between [every work interval], you can spend more time doing each one at a higher intensity, which you couldn’t sustain otherwise,” says Cowan. “If you do 10 two-minute work intervals, you’ve actually managed 20 minutes.”

Ramping up the intensity forces your body to tap into its anaerobic system for energy, because it can’t supply the oxygen required to work aerobically quickly enough; in the recovery intervals, your body reverts to its aerobic system. As the session goes on, your body relies less on the anaerobic system, because quick-release energy sources of phosphocreatine and glycogen (glucose stored in your muscles) become depleted. Your body will therefore start to rely more on the aerobic system, which releases energy more sustainably but slowly from fat. You won’t be able to achieve quite as high an intensity as you could at the start, but the upshot is a double whammy. “You’re essentially using a mixture of the anaerobic and aerobic systems, so you get an improvement in both,” says Cowan.

Respiring anaerobically has knock-on effects. “It’s like when you’re puffing and panting after running for a bus, you’re trying to repay the oxygen deficit,” says Cowan. This excess post-exercise oxygen consumption, which is more pronounced with HIIT than continuous exercise, burns a further 6 to 15 per cent more calories as your body replenishes itself.

Lactic acid and hydrogen ions produced during anaerobic respiration have to be cleared, as do hormones such as adrenaline; your body temperature and heart rate also need bringing back down: “All of those things increase the workload following the exercise.” Workload is one of the reasons why we’re not all doing HIIT all the time: you have to recover adequately between sessions. “Three sessions a week is probably okay but it’s not something that you’re recommended to do every day,” says Cowan.

If you don’t sufficiently replenish your glycogen after HIIT with quality carbohydrate sources, you won’t be able to achieve a high-enough intensity in subsequent sessions. “And, actually, diet in combination with exercise is what’s really going to help with fat loss,” says Cowan. “It’s no good training like this and eating rubbish.” Bodyweight HIIT meanwhile will, like other forms of resistance training, cause micro-tears in your muscle that need time and protein intake to repair. Research recommends 60g of carbs with between 10g and 20g of protein post-exercise to optimise glycogen synthesis.

HIIT’s risks

You can have too much of a good thing, though especially if you’re a beginner and don’t have a qualified professional on hand to ensure that the intensity isn’t too high for you. A study in the Federation Of American Societies For Experimental Biology Journal showed that interval training can actually halve the function of mitochondria in newcomers. And just one overzealous spin class can be enough to trigger rhabdomyolysis, where muscle fibres break down and leak into the bloodstream, which can in turn lead to kidney failure.

HIIT is considered safe for most if correctly prescribed, although it may raise coronary risk for sedentary people. But Cowan stresses that you should consult a doctor if you’re new to exercise or have any kind of clinical diagnosis. He also recommends starting off with six weeks of continuous, lower-intensity training before transitioning to sessions of three to four moderate-intensity reps.

Even when you can manage sessions of six to 10 reps at high intensity, you should offset them with continuous lower-intensity sessions, plus strength training to maintain muscle. Penn State University advocates no more than 30 to 40 minutes a week above 90 per cent of your maximum heart rate to prevent injury, weakness, tiredness, illness, disrupted sleep and low mood.

Another risk with HIIT is that it’s perceived as an easy option when it’s not. “You’ve really got to push yourself,” says Cowan. “It’s not that enjoyable for some people.” That said, HIIT has been rated in some studies as more enjoyable than continuous vigorous and even moderate-intensity exercise. That might be because it’s less mind-numbing, but the University of Turku, Finland, also determined that HIIT releases more painkilling endorphins in the brain. This negates the negative feelings and enhances motivation more than continuous moderate-intensity exercise.

Finally, while short workouts sound enticing, and remove the excuse of lack of time, they may give the impression that only a little exercise is necessary when most people should be getting more, not less. As the ACSM admits: “Meeting the goal of 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week [spread over three days] may prove challenging through HIIT alone.” Alternatively, the ACSM recommends 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week spread over five days, or a combination of the two. HIIT gets the arduous exercise out of the way quickly, not so you can put your feet up, but so you can enjoy more activities that feel less like hard work.

This is an extract from issue 331 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard