When she answers my call, Paula Armentrout is buzzing with the news that’s just come through. Her company’s DNA analysis and genetic genealogy service has just led to the arrest of a man for two murders that happened four years ago. It’s the 101st case of serious crime solved as result of genetic detective work by Parabon NanoLabs. The service was launched just two years ago, in May 2018.

The Cincinnati man who’s been arrested beat a mother and son to death in their home in 2016. He might have thought he’d got away with it, as at the time of the initial investigation, the DNA sample found at the crime scene matched nothing on the police databases. The case went cold.

But Virginia-based Parabon provided a new analysis of the DNA sample, which allowed it to be compared with hundreds of thousands of other DNA samples – not on police databases but on online genealogy services by members of the public wanting to find relatives through genetic similarities.

Just as in 100 other cases, the analysis revealed people related to the suspect, some distantly. Parabon’s genetic genealogists then reverse-engineered a family tree, joining the dots between the crime scene DNA and relatives using official birth, death and marriage records and obituaries, to produce a list of leads and potential suspects for whom the time, the place and the DNA fitted.

Reopening cold cases

In case 101, the process led to 51-year-old Jonathan Hurst. Mobile phone records confirmed that Hurst was in the area of the crime scene on the day of the murders. Police then tested his DNA and confirmed a match to the crime scene DNA.

“In this case, we’ve been assisting law enforcement agencies as needed for around a year and a half,” says Armentrout, Parabon’s vice president. “There are a lot of our cases in that stage, with agencies investigating leads we’ve generated or following up recommendations that we’ve given them from our genealogical perspective.”

Genetic genealogy has suddenly become big in United States law enforcement. The explosion began in April 2018, when California law authorities announced the identification and arrest of the suspected Golden State Killer, responsible for 12 killings, 51 rapes, and more than 120 burglaries in California between 1974 and 1986.

Police had drafted in the help of genetic genealogists, who pointed to former police officer Joseph James DeAngelo after they had uploaded their new analysis of his DNA data to an open-source genealogy service called GEDmatch and compared it with the DNA records of hundreds of thousands of people who wanted to research their family tree.

Read more about how science is helping fight crime:

- Identifying Jack the Ripper: old clues, new science

- Can an algorithm deliver justice?

- Should genetic genealogy really be used to crack cold cases?

Just one month after the Golden State Killer announcement, DNA engineering company Parabon launched its genetic genealogy service – also using GEDmatch – and unsolved violent crime cases came flooding in from police departments.

Parabon analyses DNA in a more detailed way than law enforcement DNA databases. It examines hundreds of thousands of DNA loci (the point on a chromosome where a particular gene or genetic marker is located) via a technique called ‘single nucleotide polymorphism analysis’ (SNP) rather than the 13 to 17 loci of traditional police ‘short tandem repeat’ (STR) techniques (see How to solve a crime with genetic genealogy below). DNA ancestry websites like GED also analyse DNA using SNP.

To date, Parabon has worked on 450 cases, with the average case being 25 years old. The company also takes on current cases where there’s an urgent need for leads. In 2018 they took on the case of a man who had raped a 79-year-old woman in Utah. Parabon’s chief genetic genealogist CeCe Moore knew that narrowing down suspects using family trees might be the only means of preventing further crimes.

“They desperately wanted to solve this case before he attacked another woman or he came back to the victim’s home again. She was petrified, couldn’t sleep at night, afraid he would come back and finish the job. So that was a very high-pressure case.” The perpetrator was arrested in July 2018, just three months after the crime.

Now competition for genetic genealogy business is growing. In February last year, Bode Technology joined Parabon in offering the service to law enforcement, followed by Verogen Inc in December (when it also acquired GEDmatch).

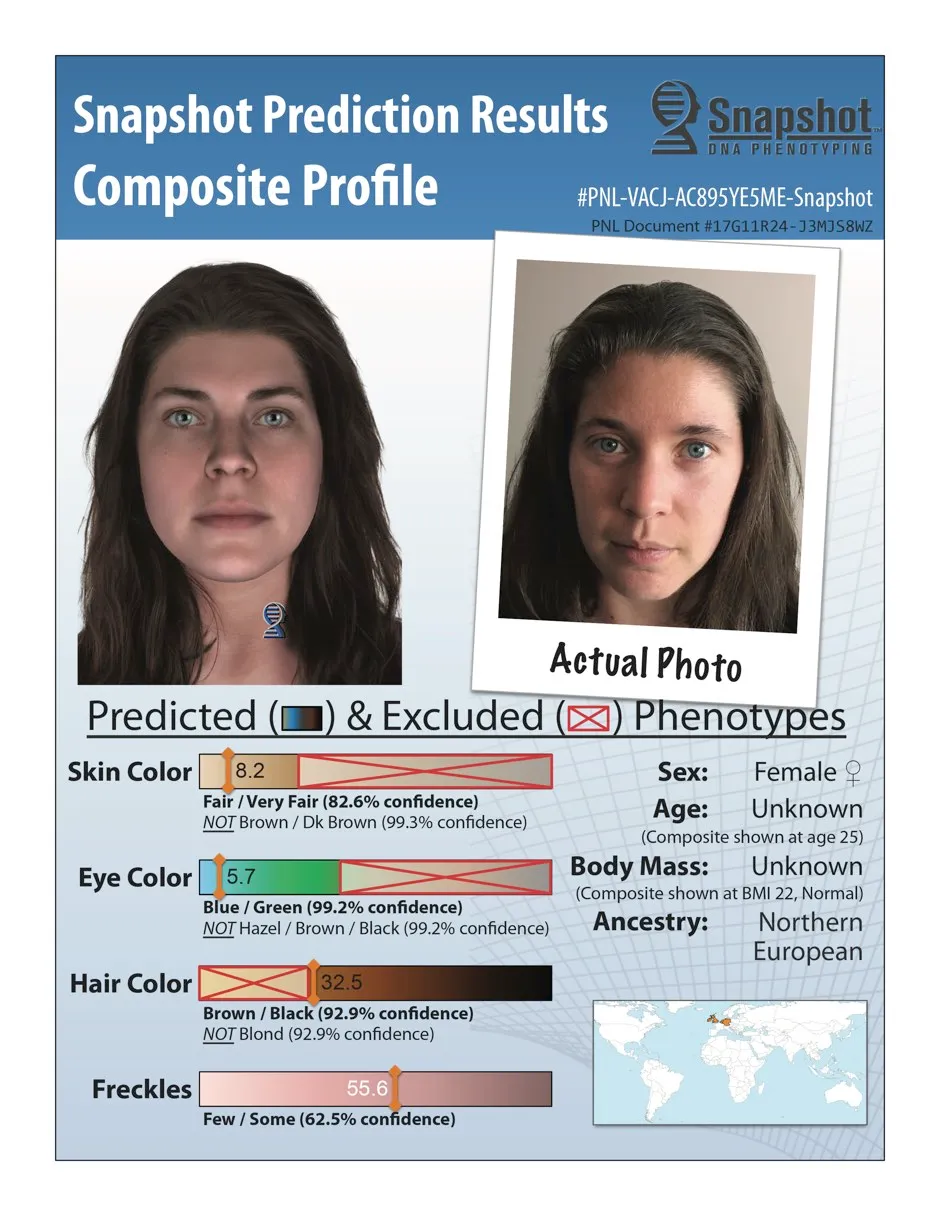

But Parabon claims no one offers a complete service like theirs, combining genealogy with a ‘snapshot’ genetic phenotyping service. This genetic phenotyping creates CGI images of suspects’ faces from analysis of key loci in their DNA. Parabon has sold this service to police forces in 13 countries.

But the rush to find new ways of catching criminals through detailed SNP DNA analysis is controversial. Rumblings started as soon as details of the Golden State Killer capture emerged. Was it right that people who submitted their personal information for the purpose of finding relatives should have their families investigated for crimes?

Some people involved in subsequent cases have complained about feeling misled that their DNA has been used to build cases against relatives.

Crime, science and ethics academics have also voiced their worries. Writing in the journal Genetics In Medicine, Dr Caitlin Curtis, genomic research fellow at the University of Queensland, said that the growth of both forensic genetic genealogy and DNA phenotyping highlights the need for greater protection of genetic data.

“Police genealogy shows how one person’s decision about their genetic data can impact not only close relatives, but distant ones,” says Curtis. “DNA phenotyping highlights how much sensitive information is contained in our genetic data.” This includes information about our predisposition to disease and mental health problems, as well as what we look like.

Privacy concerns

Some of the concern has dampened down as genealogy websites have made it clearer whether or not they are used in law enforcement programmes, and now make it necessary for users to ‘opt in’ if their DNA is to be used forensically.

Parabon says it only uploads samples to GEDmatch and now another company called FamilyTreeDNA. Other ancestry search companies, such as Ancestry.com and 23andme, do not allow access for crime-solving.

Moore, who was a well-known ancestry detective in the US before she developed forensic genetic genealogy techniques with Parabon, also had early concerns about using DNA designated for family history work for crime-solving.

Now her concern is that new privacy requirements are shrinking the DNA pool that crime samples can be compared against. Last year, GEDmatch opted its entire database out of law enforcement matching, and required each person using the service to actively opt in. The result is that Parabon now has just 200,000 people to compare against on GEDmatch, compared with 1,000,000 in 2018.

“It’s now much more difficult to solve these cases and narrow them down as specifically as we used to,” she says. “We don’t have enough data, which means a lot more work has to go into it.” Investigators may need to ask certain lines of descendants for DNA samples.

There are other limitations that may restrict expansion. Those who submit DNA to research their ancestry tend to be of European extraction – standing in the way of growth in many countries. Data protection laws in Europe are generally tighter than the United States. And some experts believe there is simply no need for genetic genealogy in countries that operate an effective crime database.

Denise Syndercombe Court, professor of forensic genetics at King’s College London, says that the UK hasn’t gone down the genetic genealogy route, partly because it already has a database that represents a more relevant population. The UK National Criminal Intelligence DNA Database, 25 years old this year, holds information on around 10 per cent of the UK population at any one time – because it includes DNA data on crime suspects as well as those who have committed crimes.

Read more about criminal behaviour:

- Can a head injury make you more prone to criminal behaviour?

- The psychopaths among us

- The minds of sleepwalking killers

According to Syndercombe Court, a complicated DNA analysis that can identify distant cousins isn’t required if your crime database is comprehensive enough. “The UK database contains information on one in eight males between the age of 15 and 45 to 50, so it’s very powerful,” she says.

In the case of unsolved serious offences, DNA can be compared to this database and it is likely to pick up close relatives – parents, children, full siblings and sometimes half-siblings and uncles.

“The problem in the United States is that they haven’t been putting their felons onto an identifiable DNA database. Most of these people could have been picked up many years ago if the United States had a proper governance structure. We have that, so my feeling is that the number of cases it would be useful for in the UK would be very limited.”

- This article first appeared in issue 348 of BBC Science Focus

How to solve a crime with genetic genealogy

- Crime enforcement agency (police department, sheriff’s office) contracts a DNA investigation company to help them crack a cold case.

- The company analyses crime scene DNA and converts it into a file representing its unique sequence of bases (adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine).

- Around 700,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) – the most common points of genetic variation between people’s DNA – in the data are examined. An Excel spreadsheet showing the information about these points (loci) would be 26 columns wide and 851,000 rows long.

- SNP DNA analysis is also used by online genealogy services to find distant relatives, while police DNA databases use a more basic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, which allows identification of only close relatives.

- The company uploads the data file to a genealogy service that has agreed to be used for law enforcement, such as GEDmatch. SNPs are compared to hundreds of thousands of other samples. The genealogy service returns a list of people who have DNA matches.

- Genetic genealogists employed by the company use this information to find common ancestors, build family trees and deduce living descendants who might fit the time and place of the crime and other evidence.