More than 30 years ago, in 1988, hypothermia expert Robert Pozos decided to unearth a document that pushed the boundaries of medical ethics and one that society had tried to forget for almost 40 years. The 68-page report, compiled by an American army officer after WWII, contained details of the horrific experiments that Nazi doctors had conducted on many people in concentration camps.

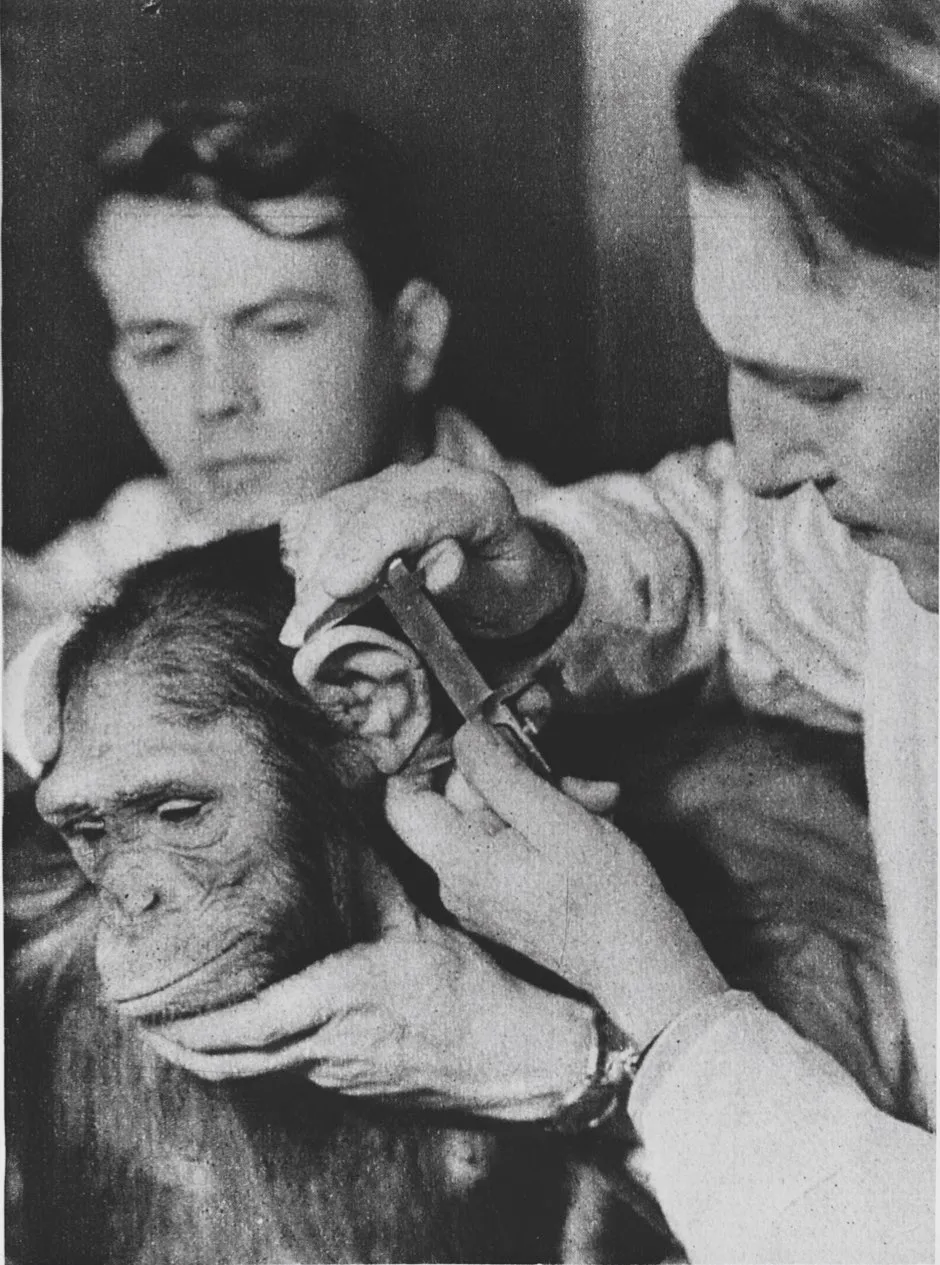

These procedures, and the conduct of the Nazi doctors stationed at camps such as Dachau and Auschwitz, make for difficult reading. More akin to sadistic torture than research, the ‘experiments’ involved Jews being frozen to death, dissected alive, poisoned, wounded without anaesthetic, or sterilised – all supposedly in the name of advancing Nazi medicine.

After the details of Nazi war crimes were revealed at the Nuremberg Trials in the late 1940s, the documents relating to these atrocities were placed in the US Library of Congress. It was imagined that few would ever want to take such material off the shelves.

Yet Pozos, the director of a hypothermia research lab at the University of Minneapolis, believed the results of some of these evil studies could be used for good. He thought that the Nazi experiments on the effects of cold – conducted in the hope that it might help downed German fighter pilots survive longer in freezing waters – could be useful in his work developing treatments for severe hypothermia.

Read more about medical ethics:

- Monkeys with human brain genes: has it crossed an ethical line?

- Medical ethics: what happens when the specialist becomes the patient?

- Human-animal hybrids: Can we justify the experiments?

The Nazis had meticulously recorded the effects of cold up to the point of death, and trialled various methods of warming people up from the brink. It was the sort of data Pozos could never obtain with volunteers or patients in a trauma ward. It could help save lives.

To some, the plan to use Nazi ‘research’ was an outrage. How could one treat accounts of human torture as if it were scientific data? Yet others, including some relatives of the victims, felt that if it meant some good could come from such terrible suffering, then it should be done.

The dilemma kick-started an ethical debate that still divides opinion today: what should we do with the results of tainted or unethical research?

Pozos was not the only person who wanted to access and analyse the Nazi research. Around the same time another hypothermia expert, John Hayward, went ahead and used results from Nazi experiments to help develop survival suits for fishermen working in freezing waters.

And in 1989, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the US urgently needed to understand how phosgene gas affects humans. Phosgene is an important industrial chemical that’s used in the production of certain plastics, but the EPA found there was barely any research on the subject of its toxicity in humans – except in Nazi literature.

The Nazis had gassed French soldiers with phosgene to record its ghastly effects; most of the prisoners died slow, painful deaths. With many US communities living near phosgene production plants, and amid rumours that Saddam Hussein was planning to use phosgene weapons on US soldiers, the EPA was forced to consider using the Nazis’ murderous study in their assessment. Eventually, they backed down amid protests.

Read more about ethics:

- In the twenty-first century, fake doesn’t have to mean fraud

- The rise of the conscious machines: how far should we take AI?

So, if good can come from an unethical experiment, should we use it? “There are two main concerns when considering whether to use this kind of data,” says Dr Sarah Chan, a medical ethics expert at the University of Edinburgh.

“Firstly, does it somehow make uscomplicit in the wrong that happened if we use it? And secondly, by using it, are we legitimising or encouraging this behaviour in the future?”

Chan believes that if people are sure that the answer to those two questions is no, then the use of results from tainted research can sometimes be justified.

“I think there are good arguments on both sides,” says David Resnik, a bioethicist at the US National Institute of Environmental Health. “In some cases, the data could be valuable for public health or advancing scientific research – but on the other hand it sets a bad precedent that data from unethical experiments will still be used.

"There are people who say you shouldn’t use it, no matter what potential good could come from it, to send the message that ethics are important and should not be violated.”

Tough decisions

While Nazi experiments mark a low point in the history of medical research, many great advances in medicine were built on the back of research that seems completely unacceptable by modern standards.

Early anatomists in England and Scotland, for example, faced a shortage of cadavers to use in their studies due to the regulations of the time. Many, including the great physician Robert Knox, learnt how the human body worked by studying corpses stolen from graves or even killed to order by the infamous murderers William Burke and William Hare.

Edward Jenner, the country doctor and pioneer of vaccination, deliberately infected his gardener’s son with cowpox as part of his early studies. Jenner’s work is said by some to have saved more lives than any other experiment in history, and earned him a medal from Napoleon. A similar experiment today might earn him a prison sentence.

In both cases, the huge strides forward that resulted from terrible scientific practices cannot realistically be ignored or undone. Despite efforts to formalise the law around human experiments following WWII, shameful practices continued throughout the rest of the 20th Century.

Who do HeLa cells belong to?

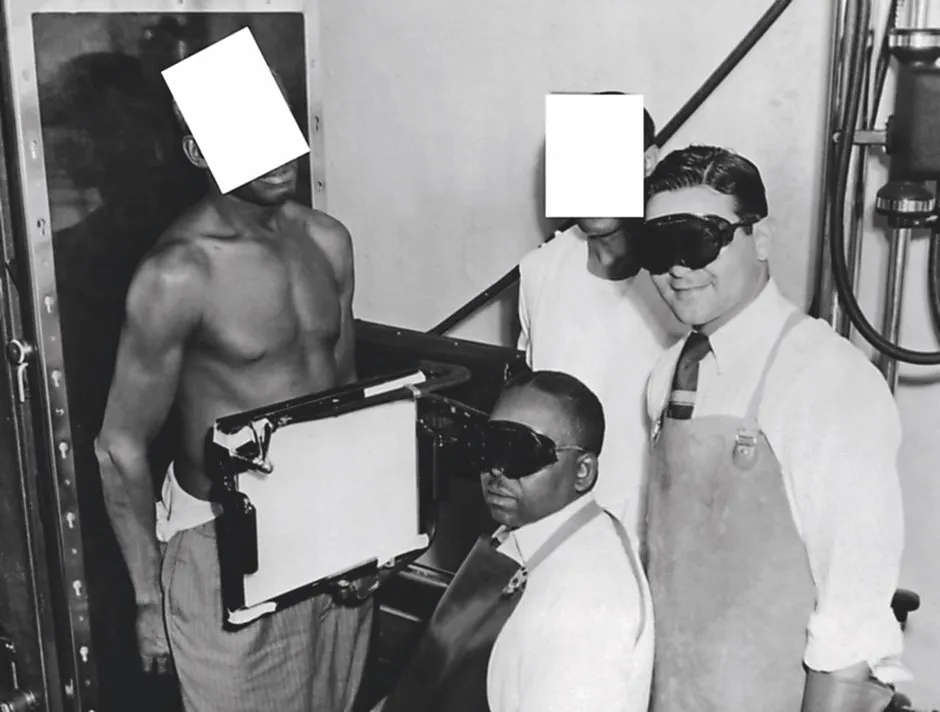

In 1951, a young black woman called Henrietta Lacks was treated for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. As was common at the time, especially for black or poor patients, she was not told that the tissue from her biopsy might also be used for scientific research.

Her cells turned out to be unlike anything doctors had ever seen: they grew quickly and could be kept alive outside the body, seemingly indefinitely.

This remarkable ‘immortalised’ cell line (known as ‘HeLa’ after Henrietta Lacks) meant scientists could conduct detailed, long-term studies on human cells in the lab for the first time.

Lacks died shortly after her biopsy was taken, and her family were not told about the HeLa cell line, even as it developed into a valuable (and profitable) scientific resource. The cells have been central to many important biological studies for almost half a century.

It is only recently that bioethicists have started to address the questions raised by the case around consent, privacy, racism in research, and the ownership of biomedical data.

Today, regulations governing the use of human tissue and genomic data are far stricter, and Lacks’s family has since become involved in decisions around the use of HeLa cells.

But is it right that scientists around the world are still keeping cells descended from this woman alive, without her permission, years later?

In the 1960s, the paediatrician Saul Krugman deliberately infected children who had intellectual disabilities with hepatitis in order to study how the disease spread. (He said the children’s home where he conducted the study was so rife with the disease they “would have got it anyway”, and was awarded several awards for his work.)

During the infamous Tuskegee Trials, run by US health agencies, black men with syphilis were studied for decades without being offered treatment so that researchers could see how their disease progressed. It was not until the 1970s that the trial was finally shut down.

Chan believes that if society can use the results of tainted research without giving credit or credibility to those who conduct it, it could help reduce the lure of notoriety that attracts some people to act unethically.

“If we think about what motivates people to engage in research we deem unethical, part of it must be that no matter how history condemns them, they will be known as ‘the first person to...’ or ‘the author of’," Chan says. "It’s about recognition. So we should think about how to use this knowledge without glorifying the acts that led to it.”

There seems to be a rise in research deemed to be unethical. A recent example is He Jiankui, the Chinese biologist who shocked the world in 2018 by announcing he had helped create the first-ever genetically-modified babies – twin girls born from embryos he had modified using the gene-editing tool CRISPR.

Scientists around the world had previously agreed that the technology was not ready to be used in this way. As well as crossing many ethical and regulatory red lines, Jiankui did not even publish his results. He simply posted a video about what he’d done to YouTube. His work still made headlines worldwide.

“The reality we have to deal with is that the dissemination of science now goes far beyond traditional academic publishing,” says Chan. “No matter what we do to say ‘you will not be credited, you will not be published in academic literature, we will not cite this research’, the world at large still knows it has happened and wants to know if it worked.”

Shifting definitions

What makes things even more complex is that the definition of ‘ethical’ and ‘unethical’ is constantly shifting. Chan thinks it is important to consider what the scientific community deemed acceptable at the time the research was done.

“If you do something wrong and at the time all your peers were also doing it and agreed it was okay, it is still wrong, but it is less wrong than doing something where all your peers are saying ‘don’t do that, it’s horrific,’” says Chan. “There is an extra wrong in flagrantly breaching the standards of your community.”

Resnik, meanwhile, says it is likely that research we consider as ethically sound today could be viewed differently in future. “Just in my lifetime there have been huge changes in how human biomedical data is handled. It was routine to take tissue specimens for surgeries, use them in research and not tell people what they were doing,” he says.

“I don’t know what the ethical issues of the future might be, but it is getting easier and easier to re-identify tissue and genetic data that we thought were completely anonymised. It’s quite possible things will change, and what we think is okay today might not be considered okay 100 years from now.”

Ultimately, when it comes to research that could save lives but comes from a terrible source, it can help test which side of the medical ethics debate you stand on by putting yourself in the position of a person whose life depends on having the best information available.

The BBC recently reported how lots of surgeons still use a book of anatomical illustrations produced by a Nazi physician, because it is considered to be one of the finest anatomical guides to the human body ever produced. The Pernkopf Topographic Anatomy Of Man was drawn using the corpses of people killed by the Third Reich, yet doctors want access to the best material to guide their work.

“If I was about to head into surgery,” says Chan, “and I knew that I would have a better chance of survival if my surgeon could refer to this book, I would want them to refer to it.” Would you?