Rob Nash had been excited tomeet the former British newsreader Trevor McDonald at his sister’s graduation ceremony.

“He was getting some kind of honorary degree,” Nash recalls. “I was sat right at the back, so allI could see was that he was wearing thisawful, garishly multicoloured graduation robe. His speech seemed to go on and on, but afterwards

I got the chance to meet him in person.”

But Nash – a psychologist at Aston University – discovered a few years later that McDonald hadn’t been at that event at all. In fact, Nash realised that even he wasn’t at his sister’s graduation. He’d invented the whole thing.

False memories like this are common. Of course, we all misremember things, but false memories can be rich in detail; not so much mistakes as elaborate fantasies. I recall a book of piano pieces that I used to play in my youth – a compilation of tunes with the wistful romanticism of Chopin and Fauré. I can still almost remember how some of them went and I’d love to find that book again. But I know I won’t, because I’ve had to gradually accept the truth: I made it up.

In an interview in The Times, novelist Ian McEwan described a similar false memory, of an “incredibly beautiful” novella that he was convinced he’d written and then stowed somewhere in a drawer after he’d moved house. He looked all over the place for the work.“I saw it in my mind’s eye, the folder, the pages, the drawer it was in,” McEwan tells me. But there was no escaping the truth. “There was no gap in which this work could have been written – my time was fully accounted for. It was a kind of haunting.”

Nash might have expected to be better at spotting his false memory, though – he specialises in studying them. But even his expertise and experience wasn’t enough to make him immune.

So why do we get false memories in the first place? Over the past decade or so, psychologists like Nash have started to suspect that, far from being a kind of useless mental spasm, false memories might actually have some benefits. It seems that they’re able to improve our mental processing: they can help us to think and may be a surprisingly handy part of our cognitive toolbox.

Remember, remember?

Remembering, says Nash, isn’t a matter of looking up a fact in a mental filing cabinet. “It’s more like telling stories,” he says – we forget and invent details. It’s hard to know when these don’t map onto reality because, as far as we can tell, “memories are our reality.” Despite decades of research, we still can’t distinguish true memories from false ones unless we can independently verify or falsify the remembered facts, which is either impossible or hardly worth the effort (why should I care if I had porridge last Wednesday – or was it Thursday?).

What’s more, says psychologist Prof Mark Howe of City, University of London“false memories are produced by the same processes as true memories – they are reconstructed from whatever mental imprint remains of the original experience.”

It’s not surprising, then, that it’s relatively easy to implant false memories in people by furnishing them with fake evidence. In 2009, Nash and his colleagues filmed subjects performing certain actions and then, days later, showed them the footage after it has been digitally doctored to include some actions they hadn’t actually carried out. Over half of the participants said they recalled – clearly and vividly – doing those things.

In other experiments conducted by Prof Fiona Gabbert and colleagues at the University of Aberdeen back in the early 2000s, pairs of participants were shown footage in which a young woman stole a wallet – but only one of the pair saw it from a perspective in which the theft was actually visible. Yet when the pair subsequently discussed the events between them, around 60 per cent of those who hadn’t seen the theft directly swore that they had.

Gabbert also showed people faked CCTV footage of a shop robbery and had them discuss what they’d seen. One of the participants was a stooge primed to introduce false ideas: the thief had a gun, right? He was wearing a leather jacket, wasn’t he? (No and no.) About three in four people later confidently recounted these ‘facts’ when questioned.

This susceptibility – what psychologists call memory conformity – is a big problem for witness testimonies at crime or accident scenes. “The consequences of memory conformity in legal arenas can be far-reaching and serious,” says Gabbert. Indeed, false memories have become a legal battlefield in crime cases.

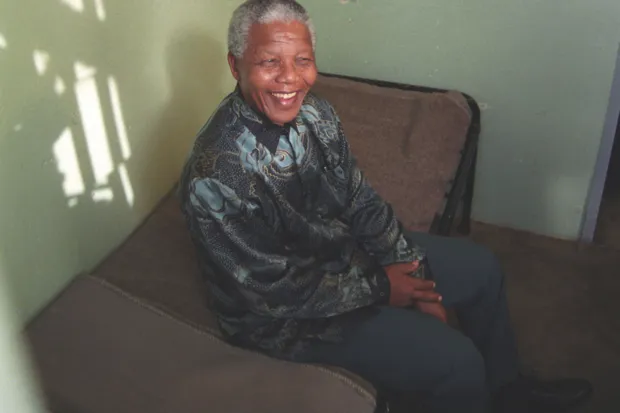

Such contagious suggestibility can lead to mass delusions, as became clear when Nelson Mandela died in 2013 and many people admitted they thought he’d died in prison during the 1980s and could even remember his funeral – a phenomenon now dubbed the Mandela Effect. Rather less sombrely, there’s the strange case of Walkers crisps packets. Many people are convinced (wrongly) that the green and blue colours for, respectively, the Salt & Vinegar and Cheese & Onion flavours used to be reversed.

Gabbert suggests that this mass effect might explain sightings of the Loch Ness monster. “People know exactly what that monster ‘should’ look like,” she says. “They’ve got a lot of visual imagery they can very easily access when they’re interpreting something [they’ve seen].”

Imagined futures

Memory is clearly an evolutionarily adaptive trait: remembering the past helps us prepare for the future. So false memories must be a bad thing, right? If we remember things wrongly, we’ll have inaccurate future expectations. It turns out that it’s not that simple.

Some cognitive scientists think that cognition works to prepare us for imagined future scenarios: if I do this, then that will happen. The process relies on gathering andretaining information about how the environment responds to our actions. In this case, sometimes a plausible guess, expressed mentally as a false memory of what happened last time, is better than having no clue at all. In this way, a false memory can suggest alternative scenarios for decision-making, priming the mind to be better at problem solving. After all, these ‘memories’ might not be wrong about what would happen in a given situation, but only about our imagined past role in such a case.

Over the past several years, Howe and his colleagues have demonstrated cognitive benefits of false memories in tests where participants were presented with lists of words (brush, gum, paste) that were all related to a non-presented word or ‘critical lure’ (in this case, tooth). When this critical lure was falsely remembered as having been present on the list, performance was enhanced on a subsequent problem-solving task where the lure word was the solution – as if the mind were saying to itself “Ah, I know this one because I saw the word on the last list.” Howe and his colleagues also found that false memories could give the same performance boost in tests on lists of words linked by analogy (‘tooth is to brush, as hair is to wash’). The effect works for all ages, from children to older adults.

Inaccurate but useful

So false memories can help us to spot associations and connections – they heighten our vigilance – and it might not matter if we get the right answer for the wrong reason (in this case, falsely believing that we saw a word on a list). To put it another way, the most useful memory might not be the most accurate one.

Memory illusions might do more than assist factual cognition. For example, they may play a socially adaptive role: we can sometimes unknowingly edit our memories, Howe says, to match what others think or feel, helping us feel more connected to them.

“Distortions of our past can serve to nurture social relationships by facilitating empathy and intimacy with others,” he says. In this vein, Nash says that his father remembered spending time with his grandfather, even though the grandfather was dead before the grandson was born.

In other words, rose-tinted glasses aren’t always a bad thing. “If we see our past in a more positive light than we did initially, that gives us a more positive image of ourselves, leading to a greater likelihood of interacting with others and maintaining social relationships,” says Howe. And such illusions can increase confidence to good effect: if you remember that you solved a problem easily last time, you’re more likely to do that this time – even if the truth is that last time you actually struggled like mad. For the brain, a false sense of confidence could be a risk worth taking.

The creative mind

The idea that false memories can sometimes have positive value is gaining ground. As Nash’s imagined Trevor McDonald encounter shows, they can be highly inventive – and he suspects that they could be an offshoot of the human aptitude for creativity. “I’m sure that most art and music contains ideas and motifs borrowed and recombined from many other sources,” he says. “So one could draw parallels between the construction of memories and of creative ideas.”

Initially, Ian McEwan was tempted to find such a creative response to his imaginary novella. “It was perfect in every way,” he told The Times, adding that if he wanted to recreate that perfection then “I’ll have to write it.”

But for a memory that’s actually false, that’s easier said than done. “By describing it in public and then seeing articles about it,” he now tells me wistfully, “the ghost of this non-existent masterpiece has fled.”

This is an extract from issue 323 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

[This article was first published in June 2018]

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard