What do you think of when you read the word “Neanderthal”? Is it clunky cavemen, with tools made of little more than hunks of rock, wandering the landscape aimlessly? Or is it something intriguing, but confusing: another kind of human which you’ve heard gave us some of their DNA, and perhaps weren’t as stupid as long proposed?

In truth, while Neanderthal discoveries are always guaranteed headlines, the things that make it into the media can only convey a fraction of the incredible new understanding archaeologists have produced in the past three decades.

Aside from the fact that some of the most amazing stuff never gets seen outside scientific journals, new findings often come buffed up in press releases, and crucially they lack the Big Picture context.

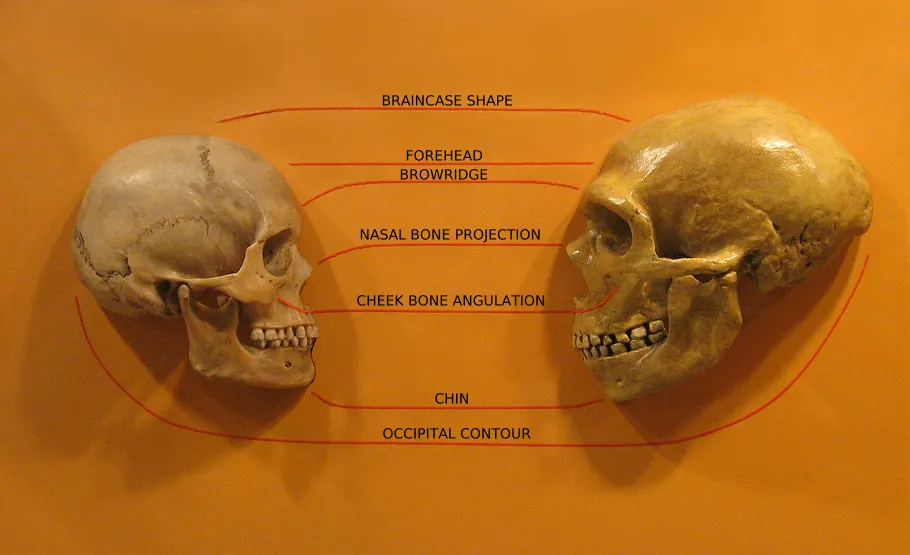

In reality, our entire view on who and what Neanderthals were has been revolutionised. The seismic discovery that they were our direct ancestors, contributing to somewhere around 2 per cent of the genome to most living humans, happened a decade ago.

Read more about Neanderthals:

- 6 reasons why Neanderthals aren't the brutish, primitive species we once thought

- Recreating the Neanderthal brain

That fact has forever changed not only what we know was going on tens of millennia ago – potentially six or more different phases of baby-making – but also how we feel about them. Yet beyond ancient genetics, ‘slow science’ in archaeology has also radically altered understanding of their lives. Years and years of work goes into excavating a site, sometimes going down barely a hand’s breadth in a single season.

Then there’s pain-staking 3D recording by laser, recording and bagging up of finds before they’re digitally immortalised in gigantic databases. And that’s just the fieldwork: once the season is over, a smorgasbord of analytical methods are available that can extract astonishing amounts of information, whatever the object in question. But all this trouble is more than worth it.

In my book Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art, all the fascinating details that haven’t had so much public attention are teased out and woven together to produce a stunning new view of their lives: a tapestry more rich and varied than we ever dreamed. And one of the biggest transformations has come in what we think Neanderthal society itself might have been like.

What did Neanderthals eat?

Trying to reconstruct the lives of another kind of human, moreover set in now-vanished worlds, is challenging, but possible. The key is searching for the interconnections between different kinds of data. Take subsistence, for example.

Studying this tells us plenty about what Neanderthals ate, but it also opens up chinks of light onto other things. Everything we see in the archaeology tells us they were expert hunters, taking the best of whatever was around them.

In some places that meant focusing on red deer with the odd horse and aurochs, while in others it was mammoth. Far from being scavengers cringing around carnivores’ kills as was once proposed, the reverse was true.

In site after site, the ordering of cut-marks made by their stone tools lies below predator gnawing damage, proving it was the fanged beasts who had to wait their turn. Actually tackling seriously big animals like woolly rhinoceros, giant deer or even extinct Mosbach’s horse (larger and heavier than the horses painted much later on cave walls) would have required both collaboration and some level of planning.

Weaponry and hunting

We might even be able to see different hunting roles in the extremely rare wooden weapons that have been preserved. At the astonishingly ancient site of Schöningen, Germany, early Neanderthals 330,000 years ago were hunting those massive Mosbach’s horses using elegant, finely tapering spears made from spruce and pine.

Excavated in 1995, these objects blew apart notions of primitive Neanderthal woodworking abilities: finely crafted from thin spruce and a single Scots pine, the concern for quality and efficiency shown in so much of Neanderthal life is revealed in the fact that their tips were all carved from the base of the stump: the hardest part.

Even more clever, the spear shafts were off-centred for increased strength. They’re almost all long, balanced just like javelins and very probably engineered for throwing, with experiments suggesting they’d be capable of carrying death over 30m through the air into the muscled necks of horses and other beasts.

One of the Schöningen spears is however much longer, at some 2.5m. It might hint at Neanderthals having a multiple-weapon system where the javelins functioned as ranged weapons, then long lances could allow precision killing while avoiding close contact with frantic prey.

Something similar might explain another very long but even thicker spear some 200,000 years younger, from Lehringen, Germany. It was found amongst the bones of a straight-tusked elephant, a beast whose death-throes you’d certainly want to stay as far clear from as possible.

Those Neanderthals were living in a very different environment to the Schöningen hunters: the world then was at the top of the climate rollercoaster, in a period called the Eemian. Some 2-4°C warmer than today, Europe was a mosaic of dense woodland, thickets and glades, and hunting animals in this kind of setting might have required quite different skills.

But lakes were still important as a place where prey could be ambushed, and from another Eemian shore locale at Neumark Nord, Germany we can see clearly that fallow deer were being hunted by spears too. In this case, the weapons themselves weren’t found, but ‘bullet holes’ Neanderthal-style were: deep, tapering punctures in the neck and hip of two massive stags.

Experimental work found that they were caused not by spears hurtling through the air, but being thrust upwards, probably from a crouching position.

Read more about Neanderthal life:

- 40,000-year-old yarn suggests Neanderthals had basic maths skills

- Shanidar skeleton discovery sheds light on Neanderthal 'flower burial'

- Neanderthals collected shells at the beach, just like us

Wherever we look in time and space, what jumps out about Neanderthal hunting is that is was organised and collaborative. There was no disorderly scrum, but teamwork both during the kill and afterwards. We can clearly see in carcass after carcass that Neanderthals knew exactly how to take animals bodies apart, and did so in a systematic way.

What’s more, they consistently made decisions about what parts to leave and take away based on the relative size of the animal and nutritional quality of the body parts. But the butchery also implies that they were transporting much of this food back to others with bellies waiting to be filled; in other words, food sharing was central to their society.

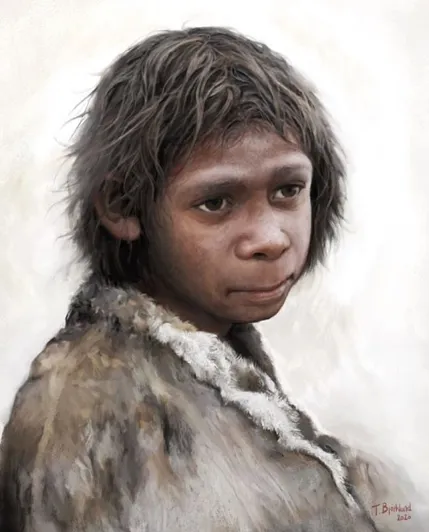

And some of those would, of course, have been children. Seeing the lives of youngsters in the past is often tricky, but without written texts or obvious toy artefacts, in deep prehistory it can feel like they’re invisible.

But we know from their own bodies that Neanderthal children must have played an active role in their groups, with well-developed muscles from carry things, walking long distances and even tooth-wear that shows little ones were beginning to learn adult skills early on.

This includes ‘clamping’ wear probably from holding animal skins while they were worked into softness with tools, a task that would have been never-ending.

Neanderthal childhood

Did Neanderthals have a ‘childhood’? In recent and historic hunter-gatherer societies, children will often go off independently in small peer groups, their days filled with a hybrid of play and practice. Astonishingly, we can catch a glimpse of this in Neanderthals: at the north French site of Le Rozel, amongst sand dunes there are over 1000 footprints.

Today on the beach, back then around 80,000 years ago the sea was lower, but the sands clearly show that most of the prints belonged to adolescents and even small children. We can imagine them running about, perhaps chasing each other, toes digging into the soft dunes; there’s even a perfectly preserved handprint pressed into the sand, as if it’s waving to us through time.

There were certainly adults around – this wasn’t a Mad Max world with no grown-ups – but actually seeing how youngsters were behaving amongst themselves is incredible. It’s not a one off either. Of the three other sites with probably Neanderthal footprints, all seem to involve teenagers or children, and this suggests other possibilities.

One of the things that hunter-gatherer children typically get up to is foraging, whether a kind of casual ‘grazing’ as they move through the land – picking berries here, grabbing mushrooms there – or more purposeful hunting.

While they do sometimes accompany adults on big game hunts, children will often learn to catch small game from their mothers or other adults staying close by, and then experiment independently.

This sort of thing might just explain some of the small game we find in Neanderthal sites, which is itself a much more common phenomenon than once believed. Perhaps things like duck, rabbit, beaver or tortoise were things taken by adults when out and about, but at one site in Spain, Cova Negra, some really tiny birds were being butchered too.

Swifts or swallows, and even a blackbird have been comprehensively taken apart with miniscule slicing along wings and limbs, and little pierced holes in the bones were made so marrow could be sucked out. The pattern of butchery is exactly like that in larger bird species also found there, but perhaps here we’re seeing the trace of youngsters learning these skills on smaller species.

Hearths are home

When they came back from their adventures in the land, children would have settled down around fires. Hearths were just as central to Neanderthal life as they still are in many of our own homes. Cores around which activities take place, but also sources of light, heat, safety. Their traces are sometimes fugitive, with ashes washed away, charcoal eroded, leaving bare hints in dark lenses or heat-reddened sediment.

But where preservation is exceptional, we can not only see the hearths – sometimes multi-layered, lit again and again – but the spreads of stuff around them. Life happened right there, whether making stone tools or using them to butcher and eat. Minute analysis shows how the fires themselves were sometimes raked out, with dead ashes dumped elsewhere into middens.

And it’s even possible to see how some fires at the rear wall were left smouldering, the gap between them and the rock just big enough for bodies to snuggle together. Laying down after a long day, stomachs full of something rich and fatty, Neanderthals would have felt the same comfort we feel.

For people moving all the time, ‘home’ was not so much a place as a state of being: night fires banked down to embers, warm on a bed of grasses and deer furs, surrounded by sleeping family.

Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art by Rebecca Wragg Sykes is out now (£14, Bloomsbury Sigma).

- Buy now from Amazon UK or Waterstones