Terry Pratchett, the author of the Discworld novels, described his dementia as an “embuggerance”. “I’ve given up my driving licence because I didn’t feel confident driving,” he told the BBC in 2008, soon after he was diagnosed. “And if I’ve got something inside out, it’s a little bit puzzling getting it the right way around again.”

People with dementia may struggle with many aspects of their lives that we all take for granted, such as remembering new information, holding a conversation, decision-making, reading, writing and understanding times and places.

What is dementia?

Dementia is a disease that damages brain cells, leading to progressive deterioration in memory, thinking and communication, as well as personality changes. Nearly 50 million people worldwide are living with the condition and numbers are expected to rise as the population gets increasingly older. About two-thirds of dementia cases are Alzheimer’s disease, but there are over 200 other types of dementia. Even within these categories, patients may present in different ways.

For example, some people may not know they have dementia or that their abilities are limited by it, while others will be aware, at least some of the time. However, as the disease progresses through its early, middle and late stages, more areas of the brain are involved and the symptoms of the different types of dementia start to look more similar.

Fast facts: Five things about dementia everyone should know

- Dementia is different from normal ageing: We may all have the odd memory lapse as we get older, such as occasionally losing our car keys, but this is not the same as dementia.

- Diagnoses can take a while: The time it takes to get a dementia diagnosis doubles when the patient is under 65.

- It's genetic: The APOE4 gene variant carries a three-fold greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease if you have a copy from just one parent, and an eight-fold greater risk if you have copies from both. One in four of us have one copy, and one in 50 have two.

- There are different types: Author Terry Pratchett had an unusual form of dementia called posterior cortical atrophy, which affects the outer parts of the back of the brain. It may be a sub-category of Alzheimer’s or a separate form altogether.

- It can be caused by certain medications: Occasionally, dementia can be the side effect of a drug that affects neurotransmitters in the brain – as with certain drugs used to treat insomnia and IBS. Once the medication is stopped, dementia goes away.

Can you see dementia on a brain scan?

Yes and no. While MRI and CT scans are often used to confirm a diagnosis of dementia – following simpler question-and-answer tests – some of the changes to the brain that may be seen in dementia are also seen in other situations, such as menopause. So it’s difficult to be absolutely sure. In fact, many people living with dementia haven’t been formally diagnosed, and it’s thought that more than a quarter of cases could actually be misdiagnosed.

In several high-profile cases, patients have been wrongly diagnosed with, and treated for, Alzheimer’s disease. One example is Alex Preston, who was diagnosed in 2014 in Leicester, UK, and continued taking medication for seven years, until he discovered the diagnosis was wrong.

For a long time, the only way to confirm an Alzheimer’s diagnosis was through an autopsy – you could only examine someone’s brain after their death. Specialists can now spot signs of the disease through sophisticated brain imaging and sampling of spinal fluid, but these techniques are more often used in research studies than in clinics.

What causes dementia?

Brain cells (neurons) are damaged and die as part of the normal ageing processes. But for people with dementia, they lose many more neurons than they normally would, and this starts to happen before the symptoms even become apparent.

In Alzheimer’s, the damage occurs when proteins clump together in abnormal ways, forming hard plaques and tangles between and inside brain cells. The plaques are composed of amyloid beta, which is present in healthy brains too, although we’re not sure exactly what its role is. The tangles are made up of tau proteins, which usually work with structural supports called microtubules to give neurons their distinct shape. But in Alzheimer’s the tau proteins separate from the microtubules and stick to each other to form long threads that block the cells and stop them passing vital nerve signals.

Current research is trying to unpick how the two types of protein interact, with suggestions that they may share a common ‘seed’ that kicks off the abnormal accumulations. Proteins are involved in other types of dementia as well, such as Lewy body dementia, where there is a buildup of alpha-synuclein protein. The brain may also be damaged by Parkinson’s disease, or lack of blood supply (vascular dementia).

Can anyone get dementia?

Dementia is fairly common. A 2020 study that looked at worldwide rates showed how the likelihood of having the condition increases with age. Although only about 70 people in every 1,000 are affected in the over-50s, anyone living to over 100 is more likely to have dementia than not, with around 660 of every 1,000 centenarians affected. Dementia before the age of 65 is usually referred to as early or young onset dementia.

It’s not easy to say what makes one person more susceptible to the condition than another, though women do seem to be affected more than men.

A combination of genetic and lifestyle factors are thought to be at play.

APOE is perhaps the gene with the strongest association. But while one variation of the APOE gene carries a higher risk of Alzheimer’s, people with a higher risk may still never go on to have dementia because of differences in lifestyle. Lifestyle factors including education, diet and sleep habits are all thought to impact on your overall risk. Certain medical problems experienced in middle age, such as blood pressure, being overweight and heart problems, can also have an impact. There is even some evidence suggesting that living in an area exposed to more air pollution can increase your risk of dementia.

How should I talk to someone who has dementia?

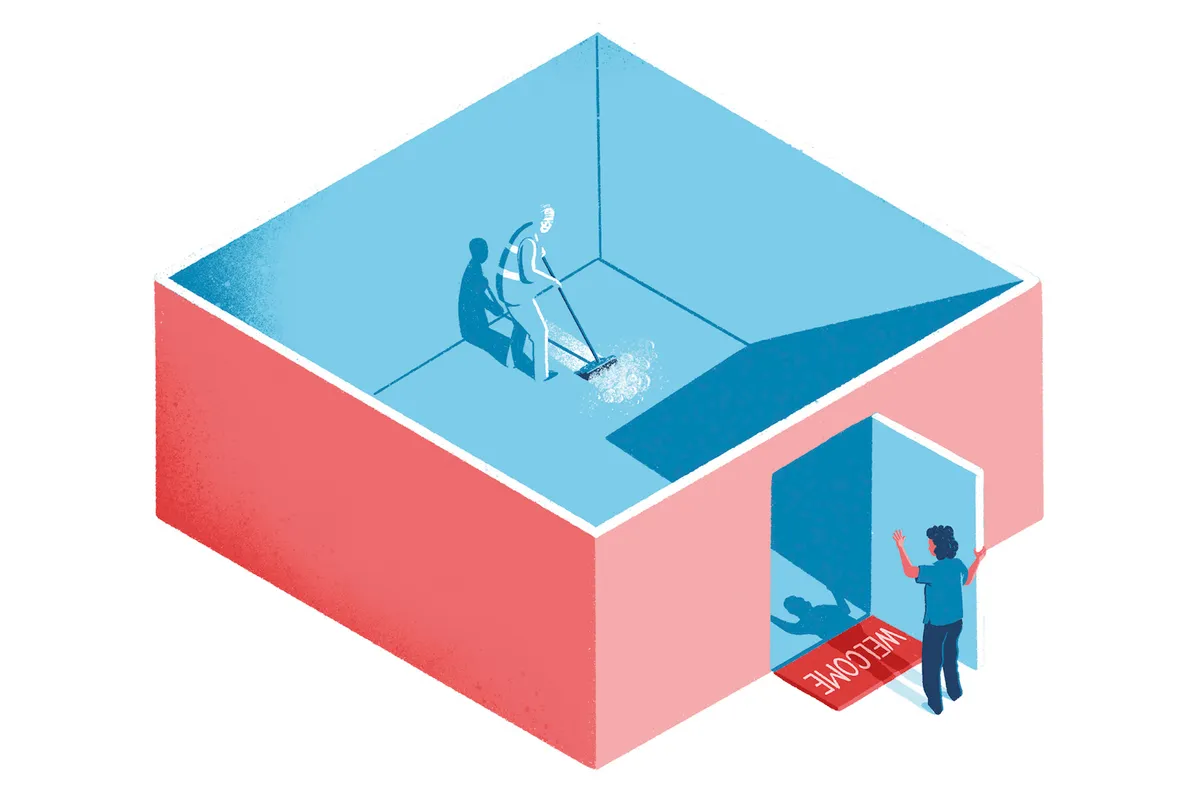

The well-known neurologist and author Oliver Sacks wrote about a dementia patient at a nursing home who thought he was still working in his old job as a school janitor. The nurses accepted his internal reality, allowing him to clean, carry keys and make checks on the doors, windows and kitchen appliances, right up until his death from a heart attack. According to Sacks, the man died content – treating him otherwise would have been a pointless and cruel assault on his identity.

The nurses’ approach was in line with what dementia experts refer to as validation therapy, as opposed to old-style, reality orientation approaches, which try to ground the patient in reality by giving them information and reminders to fill the gaps in their thinking. Following the validation approach means listening, accepting the person as they are without judgment, and focusing on their feelings and needs rather than anything we’d like to correct or change. Experts also advocate trust and respect – so maintaining a respectful tone of voice and eye contact are important.

Can we treat dementia?

Dementia cannot be cured. But experts hope that recognising the damage that leads to dementia before symptoms occur, may allow us to develop treatments that can slow the progression of the condition, or prevent symptoms from occurring at all.

The main aim of the treatments available today is to help reduce the person’s suffering, although there are also drugs and activities that are thought to benefit their brain. The most commonly prescribed drugs are called acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. These drugs help to increase levels of a key molecule – acetylcholine – involved in nerve signal transmission in the brain, by blocking an enzyme that usually destroys it. The action of these drugs can help to relieve some of the symptoms.

Meanwhile, some studies suggest that playing games likechess, doingexercise– both aerobic and strength training – and taking part insocial eventssuch as birthday parties, can help with maintaining better brain function for longer. Once the disease has progressed into the later stages, however, some of these activities may prove too stressful.

Family members often find themselves struggling to work out what’s best for their relatives. Caring for someone with dementia, and who sometimes doesn’t recognise you, can be emotionally and physically draining, hence why charities like Dementia UK emphasise support for the whole family, not just the person with the diagnosis.

Read more: