“I have four leading brands, but the one that moves like water is Venecare.” Theodore Tetteh is founder of the Tinatett Herbal company. “Anything that has got to do with sexually transmitted disease – but not HIV – it takes care of it, just like that.” It also takes care of the pain men sometimes feel when they urinate, he says, sounding increasingly evangelical. And another reason people like it so much is that, according to Tetteh, it improves their sex lives. “It’s the fastest-moving product in the country, and it works like magic.”

Tetteh is sitting in one of his 15 herbal medicine shops, in the Spintex Road industrial area of Accra, Ghana’s capital city. The shelves are a riot of brightly coloured boxes and bottles, most of them filled with remedies manufactured in a small factory a short drive away. Tinatett was one of the first companies to mass-produce herbal drugs in Ghana. Now it is one of the leading manufacturers, with around 32 products, including malaria drugs, aphrodisiacs and slimming pills. Tetteh will not reveal his sales, but says they are in the millions of Ghanaian cedi (£1 is about 5 cedi, $1 is about 4 cedi).

Over at the shop’s counter, a customer is shaking a bottle of Tinatett’s typhoid remedy and asking the shop assistant if he can open it. The last time he bought this stuff it stank like a gutter, he says. He went back to the store he got it from, where they apologised – they said it was a factory error – and gave him a replacement. The bad batch has not soured him on the remedy, he says: he knows it works, he has been using it for years.

It’s the fastest-moving product in the country, and it works like magic.

Around 70 per cent of people in Ghana depend on herbal medicines for almost all their healthcare. For many of them, there is no question about whether herbal medicines work: they just do, and they have for centuries. Bodies as diverse as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Ghana Federation of Traditional Medicine Practitioners’ Associations have concluded that if the majority of people have been using herbal medicines for generations to no obvious ill effect, they are probably safe. Actively stopping people from using traditional remedies, especially when there are few affordable, accessible alternatives, could do more harm than good.

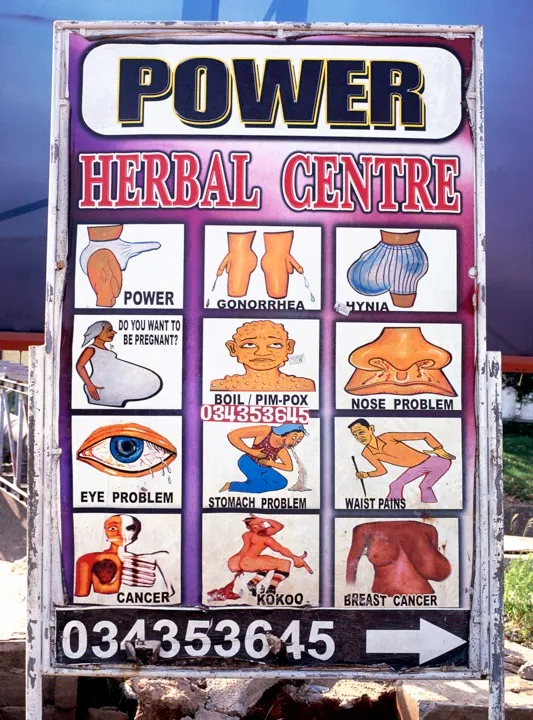

So until recently, the job of regulators has been to weed out dangerous concoctions and the most outrageous claims. But over the past ten years, herbal medicine has become big business. The practice has gone from the preserve of highly trained healers in far-flung villages to the most nakedly commercial part of the country’s healthcare industry. There are plantations and factories pumping out remedies for everything from mild exhaustion to full-blown diabetes. Herbal clinics – some of them government-backed – are popping up all over the country, and there are dozens of herbal drug stores in every major city.

Despite this, nobody – not the manufacturers, not the WHO, not the Ghana Federation, not Ghana’s Ministry of Health – knows how much this industry is actually worth. What they do know is that more and more people are using herbal medicines, and these remedies are finding their way across borders, to other countries in West Africa and to consumers in Europe and the US. This growing popularity has finally forced regulators to take a closer look at the industry, setting up a long-delayed confrontation between tradition, commercialism and science.

The heart of Ghana’s herbal boom is Drug Lane, an aptly named tangle of licensed chemical sellers, herbal drug shops and pharmacies in Accra’s teeming market district. One of the dozens of tightly packed stores is Peptee Enterprises. There’s a glass counter full of expensive aphrodisiacs about a foot from the entrance, clearly signalling the priorities of Ghanaian consumers. The shelves behind are crammed with hundreds of commercially produced herbal remedies. There are bottles of Adom Koo Mixture, extra strong, for piles and waist pain, which cost 4 cedi, and blue boxes of Medi-Moses Prostacure tea, a “natural food supplement to improve urine flow” in older men, yours for a hefty 50 cedi. There is also the highly popular Rooter Mixture, for malaria, typhoid and jaundice, which costs 6 cedi. In comparison, the WHO-recommended treatments for malaria will set you back between 12 and 30 cedi, which is a massive difference in a country where the poorest residents live on around 5 cedi a day.

On a hectic afternoon in March, the queue in front of the counter spills out into the lane. Market women in aprons pop in from their stalls outside. Men in crisp, white shirts come from across town. One customer spends 100 cedi on a prescription from the herbal medicine clinic at Police Hospital; the next guy spends just 1 cedi. A fashionably dressed young woman asks quietly for Tinatett Venecare (8 cedi). A large man conducting an obviously fake phone call asks: “My friend wants to know: which aphrodisiac works quickest?”

Manager Ebenezer Tomoah, or one of the three other people behind the counter, plucks the bottles and boxes off the shelves. One patron leans over the counter and whispers something to Tomoah, who disappears into an upstairs stockroom. He comes back down discreetly clutching a handful of glass vials containing an amber liquid, which he deposits in the man’s hands.

One woman comes in to hand Tomoah a photocopy of a letter from the Ghanaian Food and Drugs Authority (FDA) announcing the registration of “Pranko Herbal Mixture”. Tomoah says manufacturers do this all the time. Two different regulators – the FDA and the Pharmacy Council – inspect the stores on Drug Lane, he says, but the inspectors do not always know which herbal medicines are licensed for sale and which have been smuggled over the border or illegally imported from China, so Tomoah says he keeps the letters on file as proof. (The Pharmacy Council, which regulates chemists and drug stores, says it only inspects herbal medicine shops when there have been reports that they are illegally selling orthodox drugs.)

Tomoah writes the sales down in a dog-eared ledger; he is too lazy to set up a computer, he says. The store had originally started out selling toiletries in 2008, but business was slow. The owners wanted to turn it into a pharmacy, but the licence cost too much. So in 2014, they switched to the product line that’s taken over Drug Lane: herbal medicines. Business picked up quickly.

In 2015, there were almost 600 herbal medicines registered for sale in Ghana, but regulators believe there are many more available: “The system is not foolproof, it’s not like orthodox medicine where we have almost absolute control,” says Yaw Kwarteng, head of the Department for Herbal Medicine at the FDA. Still, they’re making progress, he says. “Twelve years ago there was no regulation at all.”

The FDA took over regulation of food, cosmetics, chemicals, medical devices and medicines in 1997. But this was years after the first entrepreneurs started producing herbal drugs in industrial quantities. It took the best part of a decade to convince those manufacturers that they needed regulation and safety measures such as instructions and dosage cups. It was particularly difficult to convince them that they should not be dispensing by the gallon.

Regulation has not slowed the industry down. Last year, manufacturers were pushing more herbal drugs than ever before. “We see outrageous combinations,” says Kwarteng. “If there’s money to be made, they’ll make all sorts of claims.”

The registration process for herbal medicines is designed to weed out those claims. It was influenced by places with thriving traditional medicine industries. In India, traditional approaches to medicine are part of the national healthcare system; and in China, herbal medicine is a big industry, and 95 per cent of hospitals have traditional medicine units.

In Ghana, the first hurdle for manufacturers is proving their concoction will not kill people. The medicines go to an FDA-approved lab where they are tested for stability, toxicity and contamination. Most fail that last test, Kwarteng says. The FDA visits factories to point out where the contamination is happening, which is often everywhere: these are usually pretty basic production lines with people doing everything by hand.

Then the FDA does another set of tests, to catch out manufacturers who submit fake samples or switch ingredients. “A product came for re-registration, and the initial registration went well, it was purely herb,” Kwarteng says. “Subsequent [samples] we got were laced with a Viagra-type chemical.” Some cases are even more dangerous. One product, said to boost patients’ immunity, was actually just used motor oil.

If there’s money to be made, they’ll make all sorts of claims.

But do manufacturers have to prove that these medicines work? Until 2011, as long as the concoction showed signs of working in a lab, a manufacturer could claim that it treated pretty much anything, within reason. If it was meant to treat malaria, all it had to do was successfully kill malaria parasites in a test-tube.

Then reports started coming in from big hospitals around the country. Patients were using herbal medicines to treat diabetes, cancer and even HIV. Their conditions were getting worse. There were reports of kidney and liver failure. So in 2012, the government put new, more stringent regulations in place. It would only register remedies for what were described as common ailments: upset stomachs, headaches, haemorrhoids and, curiously, malaria. That year, the number of approved herbal remedies fell from 520 to just 158. “[Manufacturers] are not able to easily register products for, say, typhoid, gonorrhoea, hypertension, diabetes,” says Kwarteng. Now, to register remedies for chronic diseases or any other conditions considered serious by the Ministry of Health, you need to perform clinical trials. There hasn’t been a single one yet.

Theodore Tetteh grew up poor. He slept on a veranda while he was at high school, he says proudly. He put himself through university in part by selling little sandwich bags of herbal remedies. They were made by a locally renowned herbalist, Gottlieb Noamesi, whom Tetteh met at a church convention. Tetteh’s own grandfather had been a practising herbalist, back in their tiny home village in Ghana’s eastern Volta Region.

After Tetteh graduated with a degree in marketing in the early 1990s, he got the kind of rocket-you-into-the-middle-class job that people in Ghana dream about. He started as a salesman for Nestlé, selling Ideal tinned milk and Milo chocolate drink to wholesalers. But Tetteh always knew he wanted to be an entrepreneur.

He didn’t know what he was going to sell, so he saved every penny he could in anticipation. “I’m very thrifty, I don’t spend money,” he says. After two years, he had enough money to buy an Opel Kadett van. He promptly quit his stable job to work for himself: buying from the wholesalers he had done business with at Nestlé, and selling to the convenience stores and petrol stations popping up all over Accra. Trying to figure out how to make his fortune, he kept going over what he had learned about why consumers buy products. “I realised that herbal medicines have been there centuries,” he says. “So why is it that my people still look down upon the product?” He concludes it is probably something to do with the spiritualism and the animal sacrifices associated with traditional medicine. Even now, foreigners will occasionally ask him if there are human body parts in his remedies.

Tinatett began as a side project in 1996. But back then there were few mass-produced herbal medicines being sold in Accra, largely because there was almost no demand for them. There was no demand for herbal products, and pharmacists did not want to stock random concoctions they knew nothing about. “When I started it was at a crawling pace, it was very, very disappointing,” Tetteh recalls.

No matter how potent your drug is, if you don’t continue advertising, the moment you stop, you see your demand coming down.

After dozens of pharmacies refused to sell his products, Tetteh started advertising, producing a series of energetic radio commercials that promised quick relief from the rigours of life in Ghana. Tetteh still writes advertising copy himself. Do you spend hours behind a computer or driving articulator trucks? Tinatett Hayan Herbal Capsules will “reduce pressure in your eyes”. Do you feel dizzy and tired after spending hours working in the hot sun carrying heavy loads? Tinatett Appitcare will “boost your energy level”. Tinatett Venecare will leave you feeling “like a virgin”.

Advertising today makes up 65 per cent of Tinatett’s operating costs. “Our type of market, the environment is such that what they hear is what they accept,” says Tetteh. “No matter how potent your drug is, if you don’t continue advertising, the moment you stop, you see your demand coming down.”

As he expanded, Tetteh went looking for new remedies. “We have these traditional practitioners in the villages across the country, who are noted for curing certain conditions,” he says. People travel from all over Ghana to see them. Tetteh visits the traditional healers bearing a bottle of schnapps (as is the custom) and a pitch. When he’s done, the healer names his price. “They’ll say, bring me a fowl, in addition to maybe some cloth, in addition to an agreed amount,” he says. “You can pay as much as 10,000 [cedi].”

Tetteh comes back to Accra, makes a test batch of the remedy and sends it to an FDA-approved laboratory. “Then, pronto, I’ve got a product.”

Sales started picking up in 2008. “It caught on well with the uneducated, because they identify with it, because most of them are from the villages, and that was what they lived on. But the educated, it took them a very long time,” Tetteh says. The company grew and started exporting to West Africa and to West African expats in the UK, the Netherlands and the US. Tetteh got an MBA, hired staff and kept expanding. He bought a dozen acres of land out in the country – enough for a completely automated factory – and a plantation of medicinal herbs. Then he came up against the new rules.

Tinatett Venecare had been approved by the FDA in 2002. In 2012, Tetteh was setting up a $275,000 deal to start exporting it, wholesale, to Nigeria. It would make him enough money to build a new, completely automated factory. He just needed a Certificate of Free Sale to get the shipment to Nigeria. So Tetteh went to the FDA. To his surprise, he says, the regulator told him that he could no longer claim Venecare was a treatment for gonorrhoea and candidiasis without performing clinical trials. “Can you just imagine?” he says. “As if it was a joke, they denied me.”

Clinical trials are expensive. Most of Tinatett’s revenue gets ploughed right back into running the company and paying the salaries of its 45 employees, Tetteh says. Besides, nobody – not the FDA, not the manufacturers, not the research institutes – actually knows how much several rounds of trials will cost. They just know they are prohibitively expensive (the Ghana Federation of Traditional Medicine Practitioners’ Associations says it has been told that trials for a single product would cost at least 50,000 cedi). All the clinical trials performed in Ghana so far have been for foreign pharmaceutical firms. The herbal drug industry is just not that advanced yet, Tetteh says: “It’s like you are taking a child who’s learning to walk – all of a sudden, you say he should run.”

Hoping to rescue his Nigerian deal, Tetteh sent the FDA a set of laboratory results from the University of Ghana’s Medical School. They had tested Venecare on bacterial isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoea (which causes gonorrhoea) and Candida albicans (which causes candidiasis), taken from patients at Accra’s Korle-Bu Hospital. The results showed that Venecare had a “significant” inhibitory effect against these isolates. He also got letters from doctors at two healthcare facilities, who swore by the stuff.

The FDA was unmoved. The most Tetteh could claim was that Venecare worked for “painful menstruation” and “proper maintenance of women”. He had to change his marketing to keep the product on the shelves. “Right now it’s causing problems on the market for me,” he says. People keep calling to ask why the labels have changed. “So I’m back to square one.”

The Medi-Moses Prostate Centre looms over one of Accra’s northern suburbs. You can see the huge red sign from the highway. Out in front there is a box truck emblazoned with an advert for Prostacure tea, the centre’s best seller. It is the only one of the 37 herbal products Medi-Moses manufactures that is sold outside its clinics.

In 2011, Ghanaian FDA inspectors found the clinic dispensing a dozen unregistered herbal medicines, including concoctions that were being sold as treatments for HIV/AIDS and prostate cancer. In an interview, the owner of the centre, De-Gaulle Moses Dogbatsey, repeatedly states that Prostacure tea is not being sold as a cancer treatment. Instead, he says, it is an old family remedy. Two cups of the stuff a day can supposedly shrink an enlarged prostate back to normal size, sometimes in just a couple of months.

Dogbatsey claims that the centre did a study of 7,000 patients – all men between the ages of 40 and 70 – over the course of two years, and the tea worked for every last one. When I ask where it was published, he points me to his website, where there is a short summary of these claims but no sign of the actual study. Despite that, this particular line of marketing has worked so well that Dogbatsey has imitators – there’s anti-counterfeiting technology on his packets of tea.

Dogbatsey attributes the product’s popularity to the traditional approach. “The world now wants to go green, everyone wants to go natural,” he says. “The solution we have provided is what the world is looking for.” He is reluctant to spell out what exactly is in that solution, noting that even Coca-Cola does not give its recipe away. “It’s a combination of selected herbs blended together to produce a tea,” is all he will say.

Packets of Prostacure tea list just one ingredient: Croton membranaceus, a shrub that is only found near a few rivers in West Africa. Its roots have been used by traditional healers for generations, to treat the symptoms of what we now call benign prostatic hyperplasia. C. membranaceus has some scientific credibility, too: the clinic at Ghana’s government-funded Centre for Plant Medicine Research has been prescribing it to patients and studying its effects for over 30 years. It is the subject of several studies about prostate health that have actually been published in peer-reviewed journals.

In rural Ghana, the country’s 40,000 traditional healers are often the only healthcare workers for miles. Far from the reach of the FDA’s inspectors, many of them, like Dogbatsey, make their own medicine. So far, no one’s figured out how to monitor or regulate them, but because they underpin communities and provide jobs, and some are famous and influential, outlawing what they do is not an option.

To protect the tradition, legislators have left a big loophole: inside the walls of herbal clinics, you can make and dispense remedies for pretty much any condition without the regulations that govern the herbal medicines sold on Drug Lane. “If they are preparing on the premises at the clinic – extemporaneously – and using it, the law allows that,” says Yaw Kwarteng. The loophole has had unintended commercial consequences. The number of herbal clinics in cities – including 18 backed by the government – has exploded.

Dogbatsey will not reveal his centre’s revenue, but business is booming. Consider this, he says: he opened his first clinic in a single-storey bungalow in 2008. They did ultrasound scans in the dining room, and the laboratory was in the kitchen. Now there are four branches of Medi-Moses, and Dogbatsey is currently building his biggest facility yet: a new herbal hospital in a gated community in Accra. “Patients will get the kind of quality treatment they can get anywhere in the world,” he says. “The machines – the gadgets – will be top-quality, state-of-the-art, then we are going to take the top-notch professionals to handle patients,” he added, vaguely.

Inside Dogbatsey’s top-floor office, a massive flat-screen television displays the feeds from 16 security cameras: the packed waiting room, a laboratory, the dispensary. Camera 10 is trained on a consulting room. Inside, an older man is pulling up his trousers.

Wendy Adu-Gyamfi is a pharmacist who hates pills. She can’t even hold them up to her mouth without getting grossed out. “Personally, when I get malaria, I prefer herbal,” she says. Many of the herbal remedies are liquids that you take like cough medicine, which she finds much easier to stomach.

Adu-Gyamfi owns Wencol Chemists. It is an oasis from the dust and fumes of the street outside, always bright, clinical and air-conditioned (thanks to a huge generator parked out in front). She says that as soon as customers start trooping in to her pharmacy, one after the other, asking for the same herbal medicine, you know the company is advertising on the radio. “This area in particular, they buy because of advertisements,” says Adu-Gyamfi. “The illiteracy rate in this country is very high, so people are just moved by recommendations and the crowd.”

Personally, when I get malaria, I prefer herbal,

Wencol Chemists stocks imported pharmaceuticals, locally made generics and a small selection of herbal drugs from manufacturers Adu-Gyamfi would use herself, such as an Indian company called Himalaya, and the Centre for Plant Medicine Research, which makes the herbal malaria drug she takes. The remedy, called Nibima, was formulated based on a growing body of evidence that an extract from the dried roots of Cryptolepis sanguinolenta plants is effective against malaria parasites.

Even so, the last time Adu-Gyamfi got malaria, the herbal drug didn’t work as well as usual. “I’ve realised that it’s not able to clear all the parasites,” she says. She gave up and took an injection of an orthodox drug. Most of her customers do the same, switching back and forth depending on the severity of the condition, and how well the treatment seems to be working.

Adu-Gyamfi probably picked up her preference for herbal medicines when she was studying to be a pharmacist at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. She studied plant medicine, and she did a project about allergic reactions to herbal remedies. “There’s a lot of research into plant medicine, but in Ghana, research work does not go far,” she says. “The industries we have now, it’s all about survival. They produce what they can market.”

Other industries have similarly been accused of making exaggerated health claims as a way to stand out. Alcohol, for instance, is a crowded marketplace in Ghana. When a local liquor company wanted to launch a new drink, it went to scientists at the Centre for Plant Medicine Research and asked them to formulate a recipe to make people both hungry and horny. The scientists obliged. The drink’s bottles also claim that it contains plant extracts that cleanse the bowels, relieve body pain, ease menstrual cramps and combat malaria. The drink became a surprise hit all over West Africa.

The Centre for Plant Medicine Research is in a town called Mampong, about an hour’s drive out of Accra. It was founded in 1975 by a doctor who wanted to combine his British medical training with the knowledge of traditional healers, to bolster tradition with science. Its herbal clinic collects clinical data from tens of thousands of patients. Yet after 40 years, the bestselling product of all that traditional knowledge and scientific research is liquor that makes you hungry and horny.

The problem is, there is very limited funding for research in Ghana. “Our research is mainly towards product development,” says the centre’s executive director, Augustine Ocloo. Ocloo moved back to Ghana after a PhD in biochemistry at the University of Cambridge. When he returned, he had to shift his own research from mitochondrial function to plant medicine. Ghanaian labs tend to be short of resources, and everything has to be imported. So, he says, “We do what we can within our limits.” Simple research into plant medicine is relatively cheap. And while the resources, many of them plants unique to West Africa, are getting less easy to obtain, there’s commercial demand for the work. While most of the centre’s funding comes from the government, it also depends on revenue from companies who pay up to 8,000 cedi for the tests required by the FDA, and from its own herbal medicine factory.

Most of the research Ocloo oversees is about safety (establishing safe doses for the active compounds in herbal medicines) and identifying commonly used herbal remedies and finding out what is behind their perceived effects. “Some of them have worked, but most often, we don’t know why they have worked,” he says. “The herbal industry is populated by people with very little science background.” Nevertheless, Ocloo does not believe that full-scale clinical trials are always necessary. “The stringent setup that you have for orthodox drugs shouldn’t apply to herbal medications that have worked over a period… It’s not like orthodox medicine where people are synthesising compounds and then coming to see whether they’ve worked.”

Besides, Ocloo says, the regulator’s push for clinical trials is largely for commercial reasons. “It’s aimed at giving our products international recognition so we can easily get into international markets.” It could mean much-needed jobs and export revenue.

“We think that it’s time to do something with our herbal medicines and see whether we can get some economic benefit from it,” says Edith Annan, the country adviser for medicines at the WHO’s Accra office. “If you want to get economic benefit, you have to do all those clinical trials.”

Annan fears the loss of traditional knowledge of plants and herbs that could be harnessed, and regrets the missed opportunities for investigation and commercialisation of such medical leads in the past. Artemisinin – a leading treatment for malaria identified from centuries-old recipes from traditional Chinese medicine – is based on an old herbal remedy. “Someone worked on it, and it became the saviour of Plasmodium-resistant malaria,” says Annan. Why isn’t that happening in Ghana?

Up a flight of stairs, past a stack of unused labels for Theodore Tetteh’s abortive Nigerian deal, is a cramped, sunlit lab with white walls and cabinets. Tetteh has bought 60,000 cedi of equipment and hired a technician to monitor every batch of medicine produced at his factory, on the orders of the FDA.

The factory is absolutely crammed with inventory: boxes waiting for labels, labels waiting for bottles, and empty bottles waiting for medicine. This March afternoon, Tetteh is getting the factory ready to make the next batch of Venecare. In one room, employees are cleaning the two 1,000-litre stainless steel tanks used to make the decoction of ingredients. In the next room, the cooling tank and a tank for adding preservatives sit idle. Opposite those is an empty space: one machine is out for servicing. A contraption that screws caps onto bottles gathers dust.

Tetteh has no plans to stop production while he figures out how to salvage his best-selling product. He is not sure Venecare sales would ever recover if he pulled it from the shelves; he has seen a lot of herbal medicine companies flame out and disappear pretty quickly. Instead, he is trying to patch together a solution. Tetteh lectures at a business school called the University of Professional Studies. According to the clinic there, students keep coming in with sexually transmitted diseases and candidiasis, so Tetteh is trying to convince them to run clinical trials. He is hoping the FDA will accept it: “I think they need to understand that this is also a business,” he says. “Nobody is interested in deceiving the public, nobody is interested in killing the people who are the mainstay of the industry.”

On a door, someone has stuck a poster that reads: “The herbal industry is changing, and so are we.”

Disclaimer: Mosaic does not endorse any of the products mentioned in this article.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard