There are myriad stories. People who were laughing an hour before they took their lives. People who were simply “not quite themselves”. People who had struggled with long-term depression. People who had a history of suicide in the family. Successful people who seemed to have everything to live for.

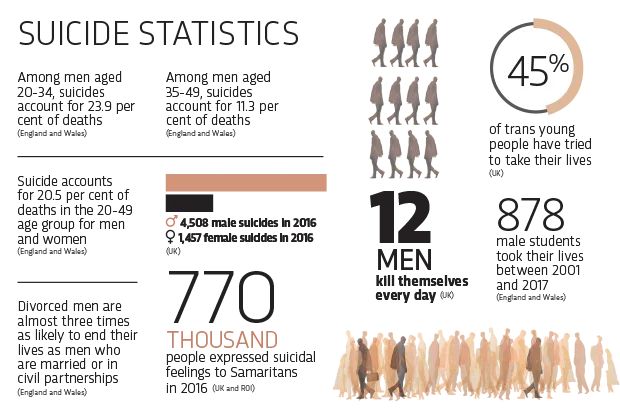

They all decided to kill themselves. Official records say that in the UK in 2016, 4,508 men and 1,457 women died as a result of suicide, but some experts believe the true numbers may be as high as double that. Men appear particularly vulnerable: in fact, suicide is the leading cause of death in men under 50 in the UK, claiming more lives than car accidents, heart disease or cancer. If it were a new disease, suicide would surely prompt a national emergency.

The reasons so many men take their lives are mysterious and infinitely diverse – a complex web of social, psychological, biological and cultural pressures. But new scientific approaches are presenting unexpected avenues for disentangling the threads. Virtual reality experiments and artificial intelligence are revealing those most at risk and could even predict who is most likely to try and take their life. Meanwhile, theories of male ‘social perfectionism’ are throwing light on why men feel they have failed. Together, they offer the prospect of better prevention.

It’s a myth, says men’s suicide charity CALM, that men don’t want to talk about their feelings

According to Prof Rory O’Connor, who runs the Suicidal Behaviour Research Lab at the University of Glasgow, changes in society are making men especially prone to the feelings of entrapment that seem to be a key driver to suicide as a means of escape. His lab works with suicide survivors in hospitals and other settings, and conducts studies in the lab to find links between suicide and psychological and social characteristics.

Some recent work, for example, has examined pain sensitivity. There is already some evidence that one of the reasons more men kill themselves than women is simply that they carry it through more effectively, using more lethal means. Working with men and women who had attempted suicide in a hospital setting, O’Connor’s research supports this view. He found that men were less fearful about dying than women, and that men have greater ability to withstand the physical pain required to carry out more lethal methods of suicide.

“There are many things in the mix,” says O’Connor. He points out that whereas in the 1990s men in their 20s were the highest suicide risk group, they have carried their vulnerability with them as they got older, so now it’s men aged 40-50 who are highest risk. There’s evidence that this is linked with recent changes to male identity in society. “Traditionally the male was the breadwinner, provided for the family, and was defined by this ‘job for life’ idea. This has changed markedly in recent decades, and men are still struggling with that,” he says.

In particular, men may be struggling with something that O’Connor describes as “socially prescribed perfectionism”. O’Connor’s theory is that some men – the social perfectionists – are acutely aware of what they think other people expect of them, whether that be in work, family or other responsibilities. Men’s social perfectionism can be judged using questionnaires asking how far they agree with statements such as “Success means that I must work even harder to please others” and “People expect nothing less than perfection from me.” O’Connor has found a relationship between social perfectionism and suicidality in a wide variety of populations, from the disadvantaged to the affluent.

“According to my model, those who are highly aware of people’s social expectations are much more sensitive to signals of defeat in the world around them,” he says. “When things go wrong in their lives – for example, if they lose a job, a relationship breaks up or they become ill – they are much more affected by that.”

Proving such links is not easy. As O’Connor says, although devastating, suicide is statistically-speaking a rare event – so capturing what leads to it through conventional research requires many thousands of people. But US psychologist Dr Joe Franklin, who heads the Technology and Psychopathology Lab at Florida State University, believes he may have found an answer to this problem. He is rejecting conventional scientific research techniques, and instead probing the causes of suicide using virtual reality and a form of artificial intelligence called machine learning.

How technology can help

“In experiments, you can’t – for example – socially reject people to see whether that makes them more likely to kill themselves,” says Franklin. “But now we can give [subjects] the opportunity to engage in virtual suicidal behaviours, using virtual reality, and study this in the lab.”

For example, Franklin’s team is interested in testing a proposed link between social isolation and suicide which has until now been unproved. First, they exposed their test subjects to standard psychological scenarios designed to make them feel mildly socially rejected. Then they put them into virtual reality helmets, placing them in a scenario where they were standing on top of a high building.

“We said to them: ‘Okay, in order to finish the task, you can either step off the side of the building, or you can press the elevator button and ride down to the ground floor. Your choice,’” he says. Sure enough, some of those who had been socially rejected chose to jump.

Franklin says there’s now good evidence that this kind of experiment provides a good ‘proxy’ for real suicide attempts, so it has genuine value in studying many contributing causes of suicide. There are potentially thousands of factors that might contribute at least a bit – and each could be important, because Franklin’s team has concluded there are no ‘big’ factors can accurately predict risk. However, the human brain is incapable of finding patterns in such complexity of causes, believes Franklin. The only way of getting to the root of suicide causes is by using machine learning.

“You give the machine every bit of information you have,” he explains. “You say: we have these 500 people who died of suicide, and these 500 who didn’t. Here’s 2,000 bits of information about them all. Now you sort out the best algorithm for pulling those groups apart.” This system could be potentially plugged into national electronic health records, both to find patterns of contributors to suicide and to identify individuals’ suicide risk.

Amid the complexity, the data from virtual reality experiments and machine learning is likely to reveal psychological ‘choke points’, says Franklin, where preventative action may work on many fronts. One possible choke point his lab is currently testing is the idea of psychologically tricking people into believing they are not suicidal.

“Our data so far indicates that how you conceptualise yourself is important: if you believe you are suicidal, you are more likely to engage in suicidal behaviours. So say I gave you a pill that was actually a sugar pill, but I told you one of its side effects was that it made people less likely to engage in suicidal behaviours,” he says. “Then I tell you that’s particularly true for people whose pain sensitivity goes down after taking it. Then I trick you into thinking that your pain sensitivity has gone down. What would very likely happen is that you would stop believing that suicide was an option for you. We know the placebo effect is pretty incredible, and if we could just flip that conceptual switch, maybe you’d get a quick and powerful intervention.”

There’s already evidence about the effectiveness of some public health choke point initiatives, effectively making suicide more difficult to perform. Firearm suicide rates in Australia fell by 57 per cent in the seven years after a gun ban in 1997, and the number of paracetamol overdoses in the UK dropped significantly when a limit was placed on the number of tablets each customer was permitted to buy (anecdotally, the extra effort required to remove a large number of tablets from the now-compulsory blister packs may also have been a factor).

In Detroit, USA, the Henry Ford Health System has reduced suicide rates by 80 per cent among service users diagnosed with depression, achieving its aim of zero suicides in 2009. Its model involves improving access to care, restricting access to lethal means of suicide such as guns, and holding staff accountable for learning and improving after each suicide. Health systems around the world are now using the Henry Ford approach as a model to reduce suicides among mental health patients.

Reaching out

O’Connor believes such large-scale public health approaches are important, but says if the male suicide problem is to be properly tackled, there need to be gender-specific initiatives. “We need to speak to men and genuinely understand what they need. That involves getting beyond referring men to clinical services, but going to where men are – sports clubs, for example – and promoting connection, wellbeing and stress management there, though not framed as ‘suicide prevention’.”

It’s a myth, says men’s suicide charity CALM, that men don’t want to talk about their feelings – they often simply don’t want to share their problems with family, friends and colleagues. That’s where confidential and anonymous helplines such as Samaritans and CALM have a vital role to play.

Clinical psychologist Martin Seager, formerly a consultant for Samaritans, agrees it’s important to target services specifically to men, and advocates men-only discussion groups across the country. “In single-sex groups men can be very bloke-y one minute, then talk about something incredibly painful the next. If men are alone in a room they are tremendously good at supporting each other.”

Another way of helping men explore their feelings without involving those close to them is via technology. Franklin’s team has developed an experimental mobile app that increases aversion to suicide and promotes feelings of self-worth via a simple association game available on iOS called Tec-Tec. Early trials are encouraging. Another American psychologist, Robert Morris, is trialling a website which provides peer support for people with depression and helps users reassess negative thoughts using cognitive behavioural therapy.

O’Connor is working with researchers at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam on a smartphone app that will help high-risk men monitor feelings of entrapment and suicidality. He believes that technology undoubtedly has a role to play. “But we need to get evidence first,” he says. “If we can demonstrate that an approach is effective in a clinical trial, then you can use an app-based approach to broaden its reach to everyone.”

- This article was first published in the September 2018 issue of BBC Focus Magazine - subscribe here

Where to find help

If you are concerned about someone, talk to them and gently ask them if they’re feeling suicidal. “It sounds scary, but there’s no evidence that asking about suicide plants the idea in someone’s head,” says psychologist Rory O’Connor. “Indeed, there’s some evidence that it protects people. Often the person who’s suicidal feels relieved that someone has actually asked them the question.”

Talk to someone

Samaritans is a safe place for anyone to talk about difficult feelings, 24 hours a day. Phone free (UK/ROI) on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org

The CALM helpline is for men in the UK who need to talk or find information and support. Open 5pm-midnight. Phone free on 0800 58 58 58

What psychology can tell us about suicide

Psychologist and science writer Jesse Bering on the factors that lead someone to take their own life, and how we might be able to help those who are at risk.

Suicide’s complex web

A background of stressful life events may predispose people to suicidal thoughts. Some other factors that may contribute to people becoming suicidal are:

1

Physical health problems

Nearly all physical health problems are associated with increased suicide risk. Suicide is twice as prevalent among those who have cancer as those in the general population, and men with cancers that affect the genito-urinary system, such as prostate cancer, may be five times more likely to take their own lives.

2

Unhappy relationships

Research shows a link between relationship breakdown and suicide risk. According to Samaritans, divorce is more likely to lead men, rather than women, to suicide. But research at the Medical University of Vienna suggests those in unhappy relationships may be at even greater risk.

3

Austerity

Evidence of the link between financial worries and suicide has been strengthened by new research indicating that suicides in young men rise notably in countries suffering from economic crisis where job losses are high. One study found that every 1 per cent fall in GDP growth sees a 0.9 per cent rise in suicide rates.

4

Screen time

The more time teenagers spend on smartphones and other electronic screens, the more likely they are to feel depressed and think about suicide, according to a new study from the University of Florida. People under 25 who are victims of cyberbullying have been reported to be twice as likely to self-harm and have suicidal behaviours.

5

Availability of lethal means

Availability of guns is particularly important in determining male rates of suicide in the United States: a new study shows that gun ownership explains 71 per cent of the variations in male suicide rates from state to state.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard