The tumour growing in the front of the schoolteacher’s brain was the size of an egg. It was the likely source of his recent headaches, balance problems, and difficulties writing and drawing. But these symptoms paled in comparison to the personality change that the tumour apparently brought about. Several months earlier, the man had been arrested after making sexual advances towards his prepubescent stepdaughter; he had also amassed a trove of pornography, including indecent images of children.

He knew his urges were unacceptable, yet claimed that his ‘pleasure principle’ overrode his restraint. He also insisted that this interest in children – and his compulsion to act upon his sexual urges – was new. It was certainly plausible, his doctors concluded. The tumour was growing in the right lobe of his orbitofrontal cortex, which is a brain area linked to social behaviour, judgment and impulse control. Once the tumour was removed, his deviant urges apparently disappeared, and his drawing, writing and balance improved. He successfully completed a Sexaholics Anonymous programme, and was allowed home. But the following year, he began secretly collecting pornography again, and a brain scan showed the tumour was regrowing. Once more, he underwent surgery to have it removed.

We often assume that paedophiles or people who commit other atrocious acts are nothing like us; they were either born bad or became that way because of maltreatment during their own childhood. Increasingly though, brain injury – caused by a blow to the head, a stroke, or a tumour pressing on neighbouring brain tissue – is being recognised as another factor that can predispose to or trigger criminal behaviour. Sometimes these injuries bring about personality changes so obvious that they raise immediate alarm bells, but more often the personality change is subtler, and the brain injury goes undetected.

It’s not only serious crimes like paedophilia or murder that are being linked to brain injury: a recent study of 613 men who were screened upon admission to Leeds Prison revealed that 47 per cent of them had experienced at least one traumatic brain injury – a serious blow to the head where they’d either lost consciousness or felt very dazed or confused – with most of them being injured before committing their first offence.

Not only could the diagnosis of such brain damage result in more effective rehabilitation programmes that reduce reoffending, but by studying the affected brain networks scientists are gaining new insights into the nature of criminality itself.

Damaged brain

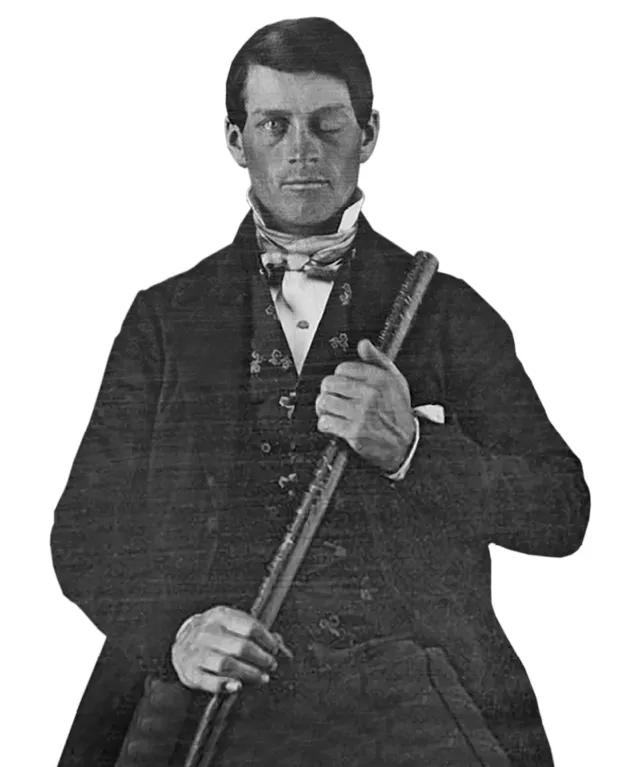

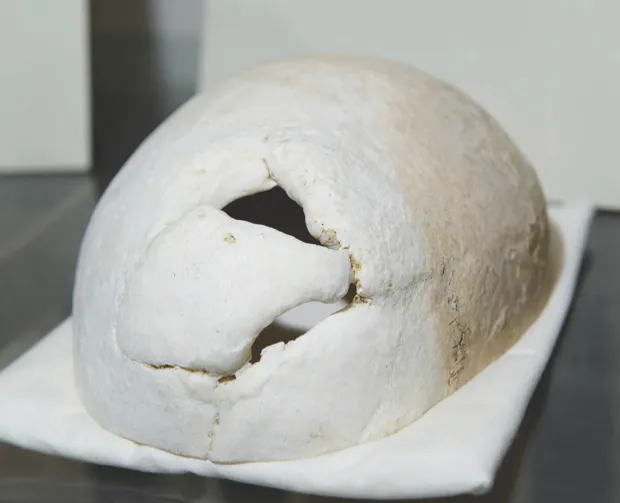

The idea that brain damage could trigger personality change has a long history. One of the first documented cases was that of Phineas Gage, a 25-year-old American railway construction worker who, in 1848, survived an accident which saw an iron rod driven through his left cheek and out of the top of his head, destroying much of his brain’s left frontal lobe.

“Gage purportedly changed from being a relatively nice chap to somebody with more antisocial personality traits,” says Dr Michael Craig, a consultant psychiatrist and reader in forensics and neurodevelopmental sciences at King’s College London. He became stubborn, foul-mouthed, and quick-tempered; friends said they no longer recognised him as Gage. “From that came the general idea that there are regions of the brain that, if affected by an injury, surgery or a tumour, can actually change someone’s personality,” Craig adds.

Since then, scientists have discovered much more about how the brain works and the relative role of its constituent parts. For instance, the frontal lobes – which include the orbitofrontal cortex, where the schoolteacher’s tumour was growing – sit just beneath the forehead and are thought to be where many higher functions such as planning, problem solving and decision-making take place. These regions also regulate impulses and social behaviour.

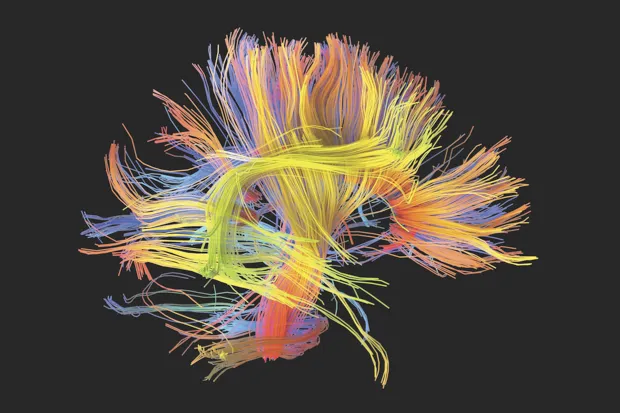

Craig and his colleagues have also studied the brains of people with seemingly more innate antisocial personality traits, such as psychopathy. They recently discovered abnormalities in the uncinate fasciculus – the ‘wires’ connecting the frontal lobe to the emotion-regulating amygdala – in psychopaths convicted of violent crimes including rape and murder, compared to non-psychopaths. “We found that it was bumpier or less well-formed than it was in people who didn’t have psychopathy,” Craig says. The worse their antisocial behaviour, the greater the abnormality seemed to be.

Other researchers have reconstructed the injuries sustained by Gage using modern imaging and computer software, discovering that he too must have sustained damage to the uncinate fasciculus, as well as to the prefrontal lobes. The uncinate fasciculus is composed of white matter, which coordinates the flow of information between different brain regions. Some of Craig’s colleagues have also identified abnormalities in the grey matter of psychopaths’ brains, which is involved in the processing of information. “There is a developing idea that it is not so much one region or another [that governs antisocial behaviour], but networks of regions that are important,” Craig explains. In the case of the uncinate fasciculus, it forms part of the limbic system – a network of different brain regions involved in our emotional and behavioural responses to the world around us.

If it’s damage to entire brain networks rather than specific regions that matters, this could help explain a puzzling finding: “As a neurologist, one of our dirty little secrets is that often the location of brain damage doesn’t link up with where we think the symptoms are coming from,” says Dr Michael Fox, an associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School in Boston, US. Take Broca’s aphasia, a condition in which people struggle to speak fluently, often as the result of a stroke. It is assumed to result from damage to Broca’s area, a region in the brain’s left anterior frontal lobe, involved in language processing. Yet when you scan the brains of people with Broca’s aphasia, the damage is often elsewhere. Importantly, these various brain lesions all connect to the left anterior frontal lobe.

Mapping the mind

In recent years, Fox has linked many such medical symptoms to different brain networks, using a map of the human brain’s connections called the Human Connectome. More recently, he and his colleagues turned their attention to criminal behaviour. The team searched the medical literature for case reports of patients who had been normal, law-abiding citizens until experiencing a brain injury, such as a stroke, brain bleed or tumour, which apparently prompted them to start committing crimes. They identified 17 case reports where the brain images were good enough that they could be mapped onto the Human Connectome. Although the damage affected different brain regions in the various individuals, their lesions all mapped onto a common network: one which becomes active when healthy people make moral decisions, such as whether it’s okay to steal a loaf of bread if your family is starving.

Although the schoolteacher’s case wasn’t included in their analysis, Fox says he is aware of it: “His lesion location showed exactly the same connectivity profile as all of the other lesions that were included in our network,” he says. So too, did the injuries sustained by Gage. But Fox cautions that many more patients need to be examined before they can be sure of the existence of a brain network that can be reliably associated with criminal behaviour. However, if their finding holds true, it could have profound social and legal implications. Already, there have been a handful of British court cases in which a defendant’s brain injury or medical condition has been used as a mitigating factor when determining their sentence or their entitlement to compensation. A reliable test would make such decisions easier. “In theory, you could take our network and say ‘does the lesion fall within this network or does it not,’ and if it doesn’t, it would certainly decrease the chances that that lesion was contributing to the criminal behaviour,” says Fox.

Around the world, courts are now turning to neuroscientific evidence as growing numbers of defendants’ claim that a brain injury or disorder was the underlying reason for their criminal behaviour. However, it doesn’t always work in their favour: in a US case, a man called Richard Hodges arrived at court to plead guilty to burglary and cocaine possession, but appeared lost, confused, and asked irrelevant questions. This prompted the judge to order a brain scan and neuropsychiatric assessment. The conclusion: Hodges was faking it.

Prisons and prisoners

Yet research like Fox’s could prompt questions about how to handle criminals with more subtle abnormalities in their brain networks – perhaps arising during development, or as a result of childhood neglect. “Do we treat them as criminals who need to be locked up and isolated from society, or do we treat them as patients in need of treatment to improve their symptoms?” asks Fox.

For now, that question remains a largely theoretical one: there isn’t yet an effective treatment for adult psychopathy, for instance. But as we learn more about the changes underpinning antisocial behaviour, the chances of us finding one grow stronger. Similar questions often cross Dr Ivan Pitman’s mind. As a clinical psychologist who has spent his career working with offenders – some of them detained in Ashworth Hospital in Merseyside – his research suggests that undiagnosed brain injury may be a contributing factor in more criminal cases than is widely recognised. It may also be impeding rehabilitation efforts.

Ashworth houses some of the UK’s most violent prisoners; men whose criminality is judged to stem from mental illness – a chemical imbalance in the brain, which could potentially be corrected with drugs. Pitman wonders if in some cases, it might arise from a physical brain injury, which is less reversible. “Once brain tissue is dead, it’s dead. The brain copes by finding new pathways for signals to go around, but it is never as effective as it was before,” he says.

Listen to the Science Focus Podcast:

He and his colleagues began reassessing some of Ashworth’s most difficult inmates using a combination of cognitive tests and brain scans: this revealed that many of them had previously undiagnosed injuries to their brains. This doesn’t necessarily excuse their bad behaviour; after all, there are plenty of people with brain injuries who don’t commit crimes. “Brain injury does not inject criminality or antisocial behaviour, but what it can do is remove some of the inhibitors,” explains Pitman.

Even so, viewing an inmate’s behaviour through the lens of brain injury can be helpful. “It means that we can start to look at things much more functionally: not that this person is bad, or is trying to upset or annoy you, but actually, perhaps this person doesn’t quite understand what is expected of them, and doesn’t quite understand the things that you understand,” says Pitman.

It also has implications for their treatment. People with brain injuries can often come across as quite normal during conversation, but they may struggle to fully comprehend what people are saying to them. They may also find it difficult to multitask, set goals or make decisions – a phenomenon called the frontal-lobe paradox.

When someone who hasn’t committed a crime sustains a brain injury, they will be assessed by a team of psychologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists to identify such deficits and develop strategies to help them function in everyday life. Such assessments aren’t usually done when someone is sent to a secure hospital or prison, but their treatment and rehabilitation often hinges on psychological interventions – such as relaxation techniques and talking therapies – which require engagement if they’re to be effective. “We have to acknowledge that this way of treating them may not work very well because they’re not able to learn and respond in the way that healthy people are,” says Pitman. “Our job is to identify the obstacles they face and find ways of overcoming them.”

Pitman’s current focus is on the general prison population. As his study of inmates at Leeds Prison revealed, up to half of prisoners may have experienced a brain injury in their past. And although many of these injuries are mild, an estimated 15 per cent are moderate or severe, which means those affected may be struggling with everyday tasks.

Brain injuries can’t be fixed, but given the right environment, people can learn to work around them to some degree. As Pitman says, “By failing these people, there’s a risk of further victims being created.”

This is an extract from issue 331 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard