Mental health conditions are not only common, they’re increasing, with one report estimating that 1 in 6 children had a probable mental health condition in 2021.

The NHS spends £15.5 billion every year on treatment and still thousands of people who could benefit from help are unable to access it. But what if there was a way to detect people who were at risk of developing a mental health condition, and intervene, before they even began experiencing symptoms?

That’s exactly what a new paper, published in the journal NeuroImage, claims to have done.

The researchers used a database of brain scans of teenagers from the Sunshine Coast, on the eastern edge of Australia. The first scans were taken when the teenagers were 12 and taken again every four months for the next five years.

The researchers were able to use the scans to predict which participants would go on to score highly in a survey about ‘mental distress’, which measured anxiety and depression symptoms.

This is particularly important because 50 per cent of mental health conditions start before the age of 14, and 75 per cent by the age of 25. And intervening early can often be the difference between someone having a single episode or living with a life-long condition.

“I think the brain is one of the most complex things on Earth and there are a lot of things we still don’t know about it,” Associate Professor Zach Shan, head of Neuroimaging Platform at the University of the Sunshine Coast’s Thompson Institute, and lead author in this new study, told me.

“More and more people believe mental health problems originate during adolescence, so our team wanted to see if we could use brain imaging to monitor or pin down when it starts.”

The teenage brain vs the adult brain

Our brains go through huge changes throughout childhood and adolescence.

First, billions of new connections are made between neurons as we take in information and our amazing, flexible brains change based on our experiences.

Then, the most used pathways begin to strengthen and a process known as pruning trims away unnecessary connections. This helps us become experts at the things we do a lot, while also making it harder (though not impossible) for our brains to change.

At the same time, the myelin, or white matter, that wraps around our neurons, protecting them and making them more efficient, grows rapidly.

This process happens at different rates in different brain areas.

Our visual system finishes pruning and reaches its full, adult-level maturity, by age 11. But other areas take much longer and the last to finish developing is the pre-frontal cortex, behind the forehead, which isn’t fully mature until our mid-twenties.

In adults, the pre-frontal cortex helps regulate our emotions, by keeping our reactive limbic system (the emotional part of the brain) in check. It allows us to control our temper and ignore that little voice that tells us everyone is staring at us.

In teenagers, the limbic system is fully developed and reacting to the environment around them, but without the control of the calm, rational pre-frontal cortex.

This might be one reason teenagers are so susceptible to mental health conditions, particularly depression and anxiety.

In fact, researchers have found that teenagers whose myelin grows more slowly in the pre-frontal cortex are more likely to struggle with their mental health.

Of course, there are also lots of other factors going on during our teenage years that might contribute to this risk profile.

“We have a lot of societal and environmental influences that play a role. You have to become more independent, find a job, get along with your peers and your family isn’t making all the decisions for you any more,” says Tobias Hauser, Professor of Computational Psychiatry at the University of Tubingen and University College London.

“And then also there’s puberty, which is a huge change in your body, and has a big impact on your brain and mental health as well.”

Your 'brain fingerprint' can identify you

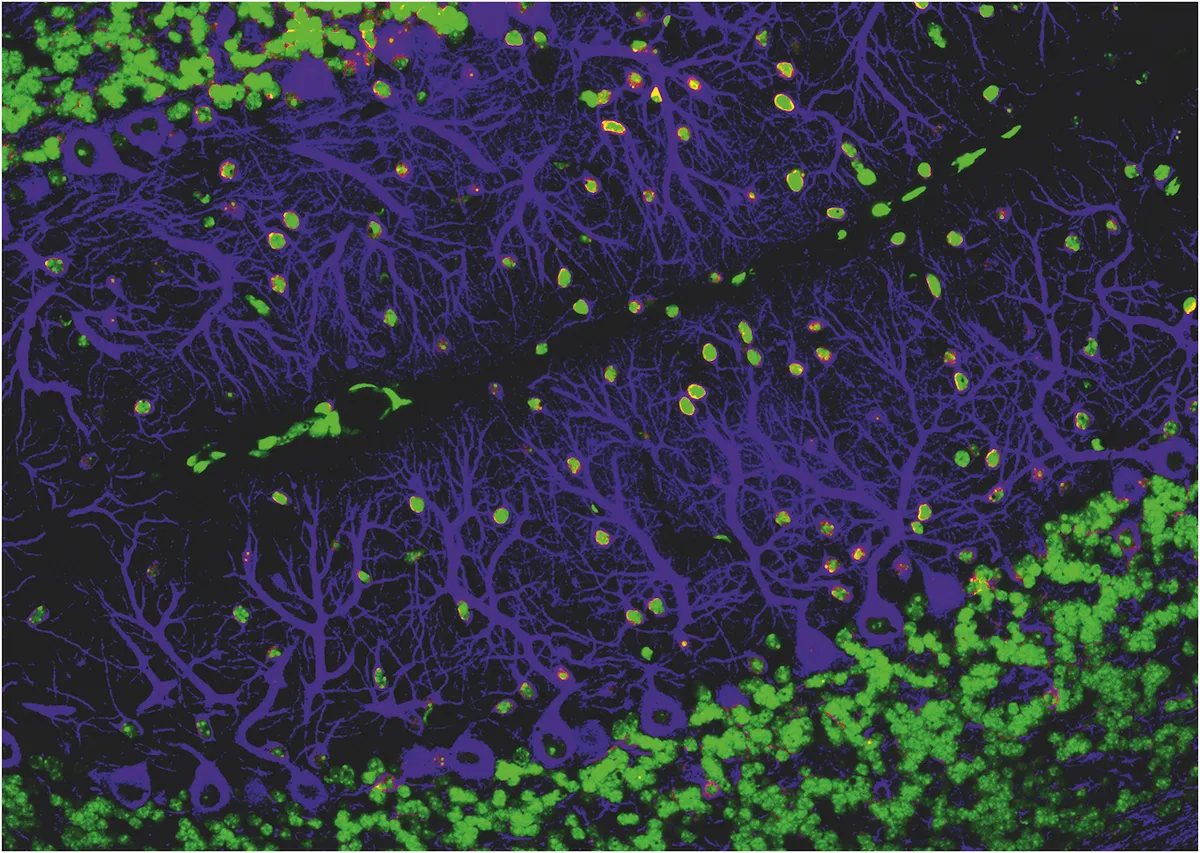

Back on the Sunshine Coast, the researchers decided to look at the ‘functional connectome’ of the adolescents in the database.

This is a measure of how different brain regions work together, in this case while people are resting. Previous research found that adults have unique functional connectomes – each of our brains is wired slightly differently and you can use this ‘brain fingerprint’ to identify people from their brain scans.

This study found that even at 12 years old, participants’ whole-brain connectomes were already unique, and the idiosyncrasies increased with age. The authors believe that this process, of our brains becoming more individual, is a vital sign of maturity.

As well as looking at the brain as a whole, the researchers also investigated networks within the brain.

They found that some of these, including one known as the cingulo-opercular network (CON), were less consistently distinct and, vitally, that teens with low levels of CON uniqueness at one point were more likely to score highly on the measure of mental distress the next time they had data collected.

Read more:

- Rise of the therapy chatbots: Should you trust an AI with your mental health?

- Can smartphone apps improve our mental health?

Cognitive flexibility and the link with mental health

The CON is a group of areas reaching from the frontal lobes to deep within the centre of the brain. Its function is still not fully understood but it seems to have a role in processing information, helping us focus and directing actions to help us achieve our goals.

Shan thinks that the fact that it’s less well developed than other networks during our teens might explain some common teenage behaviours. “If their CON uniqueness is not yet developed, teens can’t concentrate and focus for long periods.”

This network is also linked to cognitive flexibility – the ability to change our behaviour and thinking. And this might explain why it has consistently been implicated in variety of mental health conditions, from depression and anxiety to obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) – all conditions that contain an element of rigid or stuck thinking.

People who are anxious, for example, worry excessively; people with depression may ruminate, thinking negative thoughts about their lives; and those with OCD have intrusive thoughts and compulsions to perform repetitive actions. A problem with cognitive flexibility could underpin each of these issues.

So if CON uniqueness is a sign of healthy brain development during the teenage years, and problems with this network can lead to lower cognitive flexibility and higher risk of mental health conditions, it isn’t surprising that individuals whose CON is slower to develop are at higher risk of mental ill health down the line.

The researchers argue that we could use this fact to screen people and detect those at risk before their symptoms manifest. Then, just maybe, we could prevent them becoming unwell in the first place.

What are the practicalities involved?

Preventing, rather than treating, mental illnesses could save a lot of people a lot of suffering.

But it does require upfront costs, particularly if we’re talking about expensive fMRI scans, which could make it a hard sell to governments.

Luckily, there’s emerging evidence that early detection of mental health conditions could save money in the long run.

The £15.5 billion spent annually on treatment pales into insignificance compared to the amount mental illness costs the economy in other ways, for example, people being too unwell to work or needing time off to care for sick family members.

A report published in 2022 found that mental health problems cost the UK economy at least £117.9 billion every year.

A full analysis would need to be done to see whether this particular intervention would reduce the burden of mental ill health enough to provide a financial benefit, but it’s clear that, generally speaking, prevention is not only better but also cheaper than cure.

For example, a review paper found that for every £1 invested in mental health interventions in the workplace, companies saved £5 in costs further down the line.

Hence the researchers behind the brain fingerprint study think it’s an idea worth pursuing. “You can think of it like breast cancer screening,” says Shan. “We should be thinking about monitoring brain development in adolescents if we want to prevent mental health problems.”

There is, however, a significant hurdle in the way: brain scanning isn’t the most accessible way for us to do this, which Prof Daniel Hermens, one of Shan’s colleagues acknowledges: “As there have been no major advances in the prediction of mental illnesses, a reliable and objective way to do this would be of great benefit to society."

“While many hospitals (and other facilities) have fMRI brain scanners, the cost remains high, hence government subsidies are required.

"Linking brain fingerprinting techniques to other technologies, such as electroencephalograms (EEGs), will help address access and affordability, as well as allow the application of ‘wearables’ that people could use to track changes in their brain patterns that correspond with changes in mental health and wellbeing."

Gaming for mental health

One group working on an alternative is the Developmental Computational Psychiatry Lab, led by Prof Tobias Hauser.

The group’s app, Brain Explorer, collects data as people all over the world play games that test their cognitive abilities. The group found that these give similar results to tests administered in the lab, while allowing them access to a much larger and more diverse population.

As well as the games, the app asks questions about players’ mental health and the scientists behind it are starting to unpick links between game performance and mental illness.

This would be a hugely exciting development, as asking people to play a game is much easier (and cheaper) than getting a brain scan.

Smartphone apps could be used to monitor and identify people at risk

“I don’t see a future where we put every adolescent into a brain scanner. Financially and logistically, that would be a huge endeavour,” says Hauser.

“So I think the way to go is to have indices, or markers, which are easier to apply. And a smartphone app would be such a way. You could do it in schools and we can use the results to identify people more at risk.”

Instead, Hauser sees brain scans as a second-line test, to be used in tandem with other factors, like the patient’s history and symptoms. These can be used together to refine doctors' understanding of that individual and predict their outcomes.

He likens this to blood pressure testing. “Your GP measures your blood pressure. They aren’t making a diagnosis from this, but if you have high blood pressure you go for more detailed testing… Only then, using these more refined assessments, might you end up getting a diagnosis,” he says.

Whichever way we go about it, it’s clear that preventing mental health issues before they set in could be a game-changer. And with our current mental health crisis among young people, we need something to change.

I’m hopeful for a future where a better understanding of the factors that lead to mental illness, both brain-based and environmental, will give more options and more ways of providing support to those who need it most.

About our experts

Dr Tobias Hauser is a professor of Computational Psychiatry at the University of Tubingen and University College London. His research has been published in journals including Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, the European Journal Of Neuroscience and the Journal Of Experimental Psychology.

Dr Zach Shan is head of Neuroimaging Platform at the University of the Sunshine Coast’s Thompson Institute. He is a biomedical engineer specialising in brain imaging and analysis of brain imaging data.

Prof Daniel Hermens is Deputy Director at the University of the Sunshine Coast’s Thompson Institute. Leading the Youth Mental Health and Neurobiology program, his research tracks brain development throughout its most dynamic phase of adolescence.

Read more: