You’re facing a big decision – whether that’s to go into a business partnership with a friend, say, or put money into a promising new idea.

It’s a tough call, as there are very few hard facts to go on. So it’s time to use your second brain. Don’t worry, you’ve probably used your second brain countless times before; it’s just that when you did, you probably referred to it as ‘gut instinct’. New research is showing that this age-old phrase is surprisingly accurate.

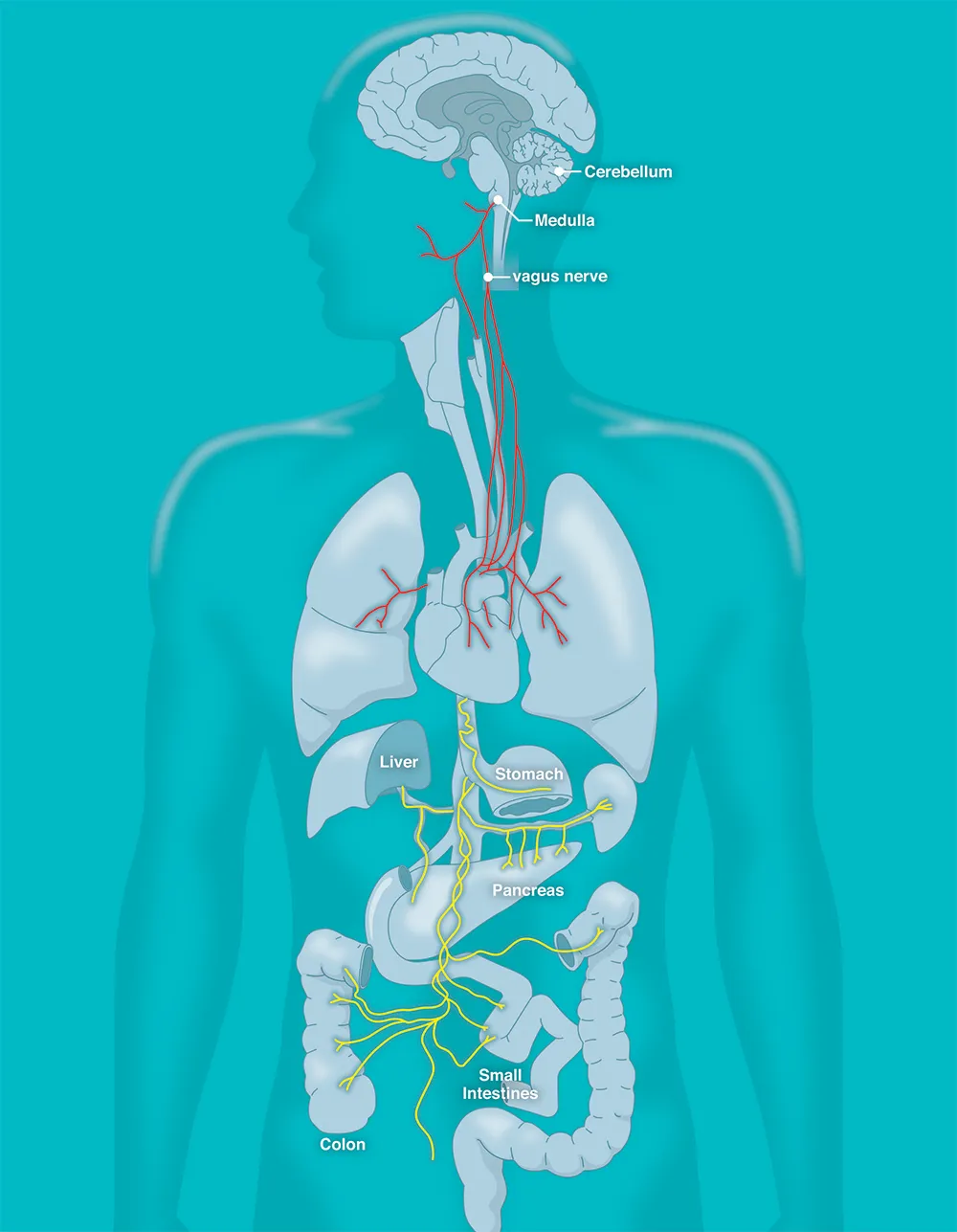

We really do have a second brain that influences our judgment, and much else besides. Known as the Enteric Nervous System (ENS) – enteric meaning ‘to do with intestines’ – it’s an extensive network of brain-like neurons and neurotransmitters wrapped in and around our gut.

Most of the time, we’re unaware of its existence, as its prime function is what one would expect: managing digestion. Yet the presence of all that brain-like complexity is no coincidence.

The ENS is in constant communication with the brain in our skull via the body’s own information superhighway – the vagus nerve. And it’s now becoming clear that all those signals flowing back and forth can influence our decisions, mood and general well-being.

“Your gut has capabilities that surpass all your other organs, and even rival your brain,” says ENS specialist Dr Emeran Mayer of the University of California, Los Angeles, who is author of The Mind-Gut Connection, an account of the science of the ENS. “This second brain is made up of 50-100 million nerve cells, as many as are contained in your spinal cord.”

Researchers worldwide are now racing to explore the implications. The results are revealing the key role of the ENS in everyday health – and also what happens when it malfunctions. Links are emerging between the ENS and a host of disorders ranging from obesity and clinical depression to rheumatoid arthritis and even Parkinson’s disease.

That, in turn, is opening up new approaches to treating these conditions, with some quite promising results already appearing.

ENS and the microbiome

The ENS and the brain-gut connection look set to become a major focus for 21st-Century medicine. Yet the first hints of its importance actually emerged over a century ago, when researchers began making some strange discoveries about our digestive system.

Experiments by British doctors on animal organs revealed that the stomach and intestines have the bizarre ability to work autonomously, processing food even after they’ve been removed from the rest of the body. The ENS, it seemed, was clearly far more sophisticated than just a bag of nerves surrounding various organs, though the reason for its complexity was far from clear.

Then in the 1980s, researchers made another startling discovery: the ENS is awash with neurotransmitters, the biochemicals that are vital to brain activity. By the late 1990s, researchers began talking of the ENS as the body’s second brain.

That led to some misconceptions, says Mayer: “There was a lot of hype around the idea that the ENS may be the seat of our unconscious mind.”

The reality is more nuanced and involves another of the key targets of current medical research: the microbiome. This vast array of bacteria, viruses and other organisms is found throughout the body, but the biggest and most diverse collection is in the gut.

Like the ENS, these microbes are principally focused on the complex business of dealing with digestion. But their behaviour in the gut is constantly monitored by the ENS, and the information is relayed via the vagus nerve straight to the brain.

Read more about your microbiome:

- 15 tips to boost your gut microbiome

- The British microbiome

- Psychobiotics: Your microbiome has the potential to improve your mental health

A clue to the key role the state of our gut plays in our well-being comes from the fact that around 80 per cent of the vagus nerve is dedicated to reporting information to the brain. Suddenly, the idea of having a ‘gut instinct’ no longer seems so ridiculous.

We’ve all experienced sensations like queasiness and butterflies when faced with challenges, or felt ‘sick to the stomach’ when things don’t go well. According to Mayer, the brain labels memories of such situations with the effect they had on our gut.

The result is a rapid-access library that helps assess new challenges based – literally – on gut feeling rather than conscious, rational thought.

That’s not to say you should always go with your gut. “The quality, accuracy and underlying biases of this gut-brain dialogue vary between different individuals,” says Mayer.

While fast, its response can also be warped by other life events or even what you ate. And sometimes it’s just plain wrong. Faced with a huge financial decision, cool-headed analysis is a better bet than a snap gut decision.

ENS and mental health

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the ENS influences our brain at deeper, more subtle levels as well. Evidence is emerging that the ENS influences our mood, and even plays a role in depression.

Exactly how it does this is still unclear, but researchers are currently focusing their efforts on one of the many neurotransmitters that are found in the ENS: serotonin.

Imbalances in serotonin have been implicated in depression for a long time, which is why it is the target of many drugs that have been developed to treat the condition, such as Prozac.

Yet around 95 per cent of the body’s serotonin is produced not by the brain, but by the ENS, and is affected by what we eat, the state of our microbiome and the signals sent along the vagus nerve to the brain.

This mind-brain connection is now leading to new approaches to treating depression. Studies have found that sending electrical pulses along the vagus nerve can influence the brain’s use of serotonin, helping to alleviate severe depression.

Until recently, fitting patients with the necessary pulse-generating implant required invasive surgery.

But researchers at Harvard University and the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences have now developed a device that stimulates the vagus nerve externally, at the point where it’s most easily accessible: the ear.

Tests of the clip-on device with 34 patients with clinical depression has already produced promising results, says research team member Dr Peijing Rong: “This non-invasive, safe and low-cost method of treatment can significantly reduce the severity of depression in patients.”

Recognition of the key role of the vagus nerve in gut-brain communication is leading to other conditions being treated in similar ways – including obesity.

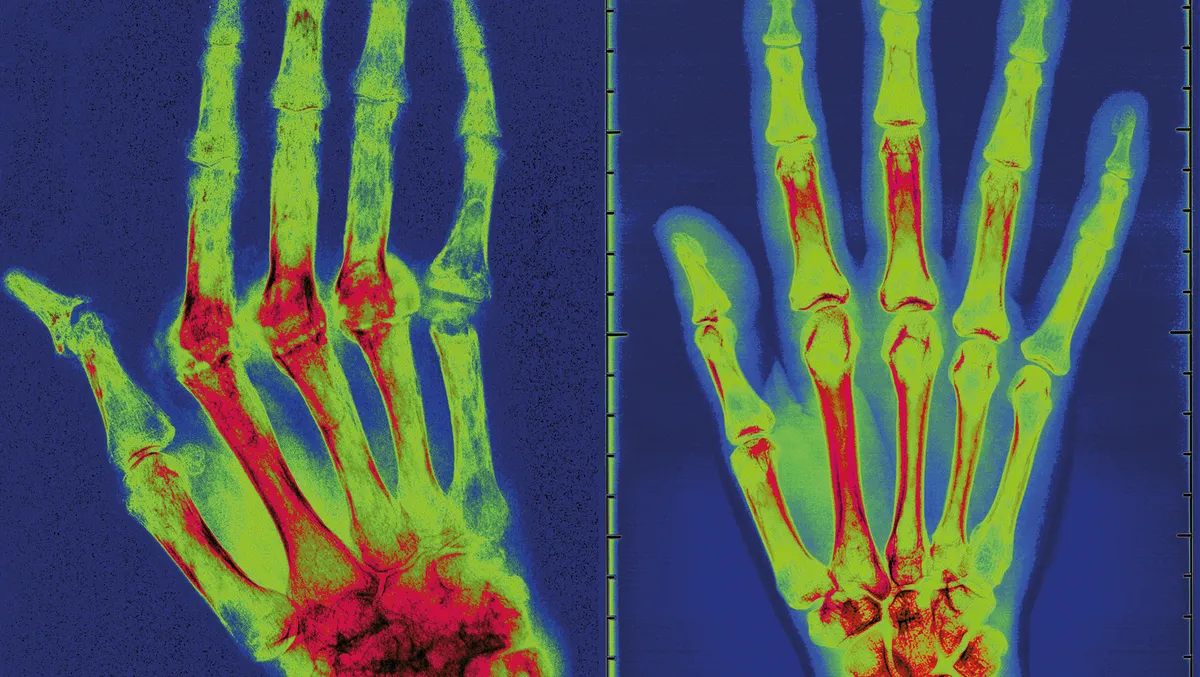

In 2016, the journal Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences published the results of an international study of vagus nerve stimulation among patients with the crippling disease rheumatoid arthritis, which affects half a million people in the UK alone.

The technique, which currently requires an implant, appeared to benefit some patients by reducing inflammation in the body, a phenomenon also linked to many other conditions including ulcerative colitis and cancer.

Meanwhile, evidence is emerging for surprising links between the gut and other disorders usually thought to start elsewhere, such as Parkinson’s disease.

Read more about mental health:

- Magic mushrooms and mental health: could psychedelic drugs treat depression?

- Hallucinations: the many ways we experience things that are not there

A team led by Dr Elisabeth Svensson at Aarhus University, Denmark, recently reported that patients whose vagus nerves had been severed to treat other medical conditions benefited from a substantially reduced risk of developing Parkinson’s.

Work is now underway to understand this link, and use it to treat or even prevent the degenerative nerve disease. “To be able to do this will naturally be a major breakthrough,” says Svensson.

Complex connections

The explosion of research interest in the ENS is impressive, but it’s still early days in the quest to understand precisely how it works. Most of the trials of vagus nerve stimulation are pilot studies whose positive results may fade in bigger trials.

The sheer complexity of the gut-brain connection is daunting, says Dr Xiling Shen of Duke University: “Disorders like irritable bowel syndrome are only diagnosed by symptoms, but their causes and mechanisms are completely unknown.”

Together with colleagues at universities across the US, Shen is working on a key tool for unlocking the mysteries of the body’s second brain: a device capable of monitoring the action of the ENS in real time.

The prototype, which is currently being used in animal studies, features an electronic implant that can show how the ENS responds to different neurotransmitters, drugs and diseases.

This is already casting new light on how the second brain interacts with the one in our skull. According to Shen, by stimulating the gut to produce serotonin, it’s possible to affect eating behaviour, alleviate and even enhance brain functioning.

And this is just the start, explains Shen: “We are currently developing non-invasive ENS recording technology that will allow personalised and precision treatments.”

At this rate of progress, we may all have to prepare ourselves for the day when our family doctor clips a device on our ear with the words: “I just want to check on the state of your second brain.”

- This article first appeared in issue 302 of BBC Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here