Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, US

Yellowstone’s Grand Prismatic Spring is the largest hot spring in the US, and it boasts a veritable rainbow of colours. Hot water bubbles up through a crack in the Earth’s crust, supplying the spring.

Very little can survive in the centre of the spring, where temperatures can reach nearly 90°C, so the water here is a pure blue. But away from the centre, colourful, heat-loving bacteria begin to thrive, and the spring’s concentric rings of temperature create different niches.

The colours come from the photosynthetic pigments, such as chlorophyll and carotenoids, that the bacteria use to manufacture energy from sunlight.

Carotenoid-rich Synechococcus bacteria are responsible for the innermost yellow ring, while slightly further from the centre, Synechococcus rubs shoulders with other carotenoid-containing bacteria, giving more of a tangerine colour. Closer to land, where the bacteria are more diverse still, the cocktail of pigments creates a rusty Martian hue.

Zhangye National Geopark, China

These impressive formations are sometimes called the ‘Rainbow Mountains’. When the strata (bands of sediment) were formed, around 100 million years ago, they were laid down horizontally, like the layers of a cake.

The colours came as iron-rich minerals permeated the sediments and interacted with the water and oxygen there. Iron reacting with oxygen forms iron oxides, which can be bright red, green or grey, depending on the amount of oxygen present. This, in turn, would have been influenced by the climate.

“Red layers probably reflect a drier, more desert-like environment when the rocks were being formed, whilst paler layers suggest wetter conditions,” says geologist Prof Jan Zalasiewicz at the University of Leicester.

As the sediments were buried and slowly turned into rock, groundwater may have added a further imprint of chemistry and colour. The layers acquired their characteristic tilt when colliding tectonic plates crumpled and forced the rocks upwards.

See more fantastic nature photos:

- 14 stunning photos of birds making incredible journeys across the Earth

- 19 beautiful pictures from the Nature TTL Photographer of the Year 2020 competition

- 36 amazing photos from the Underwater Photographer of the Year 2020 competition

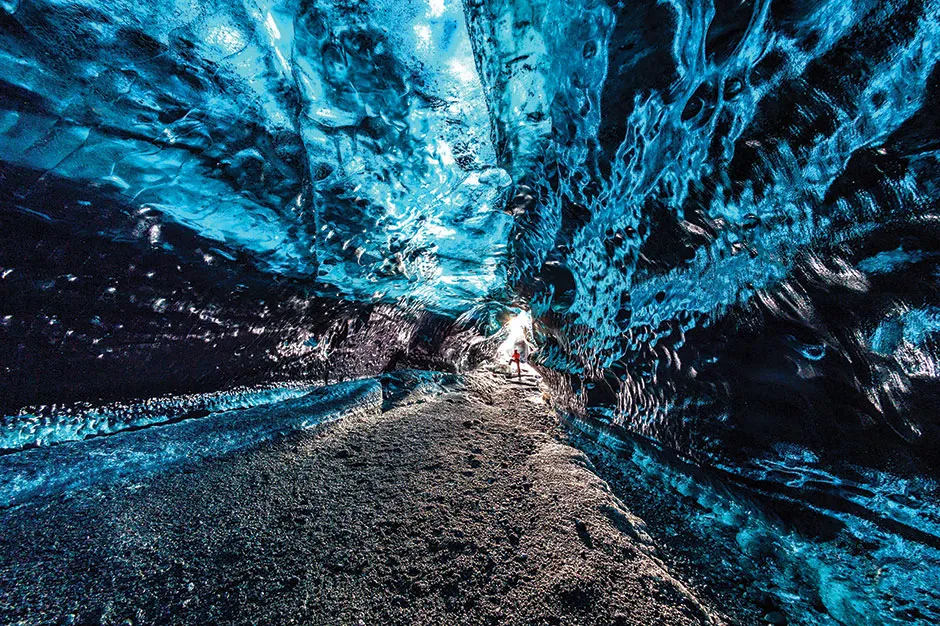

Vatnajökull ice caves, Iceland

Stepping into the Vatnajökull ice caves is like setting foot in another world. Enormous passages carved into the heart of Iceland’s largest glacier cast a starry blue light so surreal it wouldn’t look out of place in a van Gogh painting.

The caves are formed because of the seasonal freeze/melt cycles. In spring and summer, meltwater floods down into the glacier, creating a network of underground rivers that erode the ice. In winter, when the floods dry up and the rivers recede, the caves become exposed.

The walls of the caves are made of ice that is thousands of years old. Compressed by the weight of the glacier, the ice is dense and lacking in air bubbles.

This results in big ice crystals, which absorb the longer wavelengths of visible light – red, orange, yellow and green. The remaining light that we see is composed of shorter wavelengths of blue and violet, giving the ice caves their characteristic sapphire-coloured hue.

Okayama Prefecture, Japan

Their lives may be brief, but they are dazzling. Although adult fireflies live for just a few short weeks, they light up the undergrowth with their bioluminescent backsides.

In Japan, the show begins around early June, as the insects emerge from their pupae and start looking for love. They attract mates by emitting carefully choreographed bursts of light from specialised organs in their abdomen.

Many species have their own unique flash pattern, which helps them to identify members of their own kind, and studies have shown that females often prefer males who flash more frequently and intensely.

Don’t, however, be fooled by their name. ‘Fire-like’ they may be, but ‘fly’ they are not. Fireflies are actually beetles belonging to the Lampyridae insect family.

Caño Cristales, Colombia

The Caño Cristales river tumbles through the mountainous Serranía de la Macarena National Park in Colombia. In June, when the rains come and the river level rises, the clear waters become awash with colour, thanks to an endemic herb called Rhyncholacis clavigera.

Clinging to the bedrock, the aquatic plant bursts into life and causes the river to turn scarlet. “Its colour is quite unique amongst the world’s freshwater aquatic plants,” says biologist Dr Carlos Lasso from Colombia’s Humboldt Institute.

“Rhyncholacis clavigera helps to structure the aquatic ecosystem by providing food and habitat for native species,” he says. “Many species of invertebrates and fish depend on it, and mammals, such as the tapir, feed on it too.”

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California, US

Every couple of years, when the conditions are just right, the Californian desert puts on a wildflower display so spectacular that it leaves many onlookers speechless.

“Most people are shocked because they’re not expecting to see such beauty in such an arid landscape,” says botanist Prof Mark Chase from Kew Royal Botanic Gardens.

The environment is harsh, so most of the time, many wildflowers such as these pink desert sand-verbenas and yellow California evening primroses sit it out underground as seeds. Then, if there’s a good amount of rain in the winter months, they explode into life the following spring, flowering, producing seeds and dying within a few short weeks.

“Competition to attract pollinators is intense, so the plants have evolved to produce a lot of nectar and also to be very colourful and showy,” says Chase.

See more amazing photos:

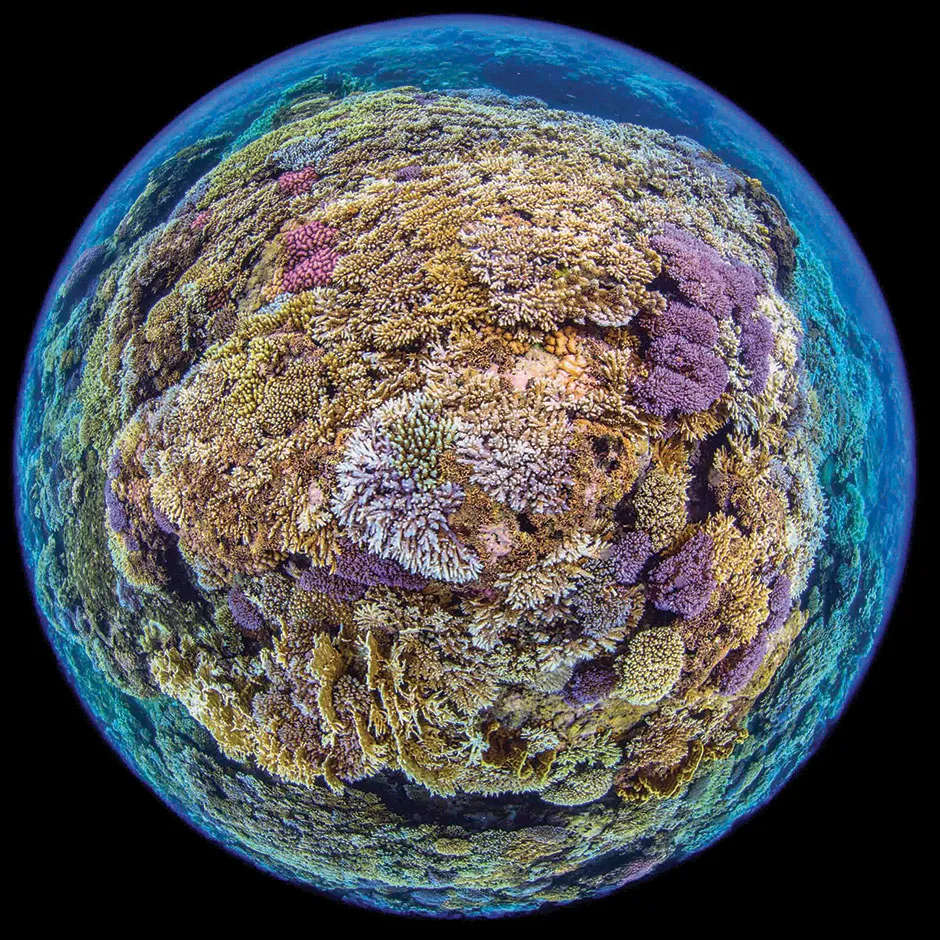

Palau & Guam, western Pacific Ocean

Corals come in many vibrant shades. Some, like these soft-bodied corals in Palau (first image), come in Barbie pinks and neon oranges, while others, like these hard-bodied corals in Guam (second image), display a more muted range of tones.

Soft-bodied corals produce bright pigments which help provide protection from the Sun by reflecting sunlight. Hard-bodied corals, which are the ones that build reefs, owe most of their colour to the symbiotic algae living inside their cells. The algae provide the corals with nutrients and sunscreen, and the corals provide the algae with a safe place to live.

The hard-bodied corals in this photo are healthy. But when water temperatures increase, the algae can be ejected, making the coral look white, or ‘bleached’. Sometimes, however, ghostly hints of colour remain, says coral expert Dr Jamie Craggs at London’s Horniman Museum. “That’s the coral’s natural pigment.”

- This article first appeared inissue 350ofBBC Science Focus