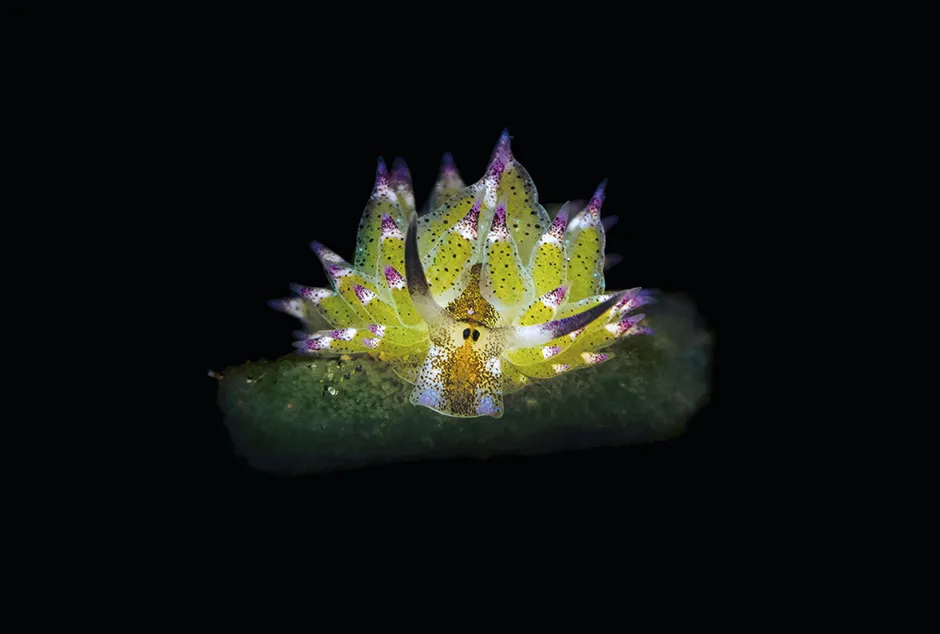

Leaf sheep sea slug (Costasiella kuroshimae)

It looks like a tiny, cartoon sheep, but this is in fact one of more than 4,700 known species of sea slug that creep and occasionally swim through the ocean. Known as the leaf sheep (Costasiella kuroshimae), this sea slug lives around coral reefs, where it grazes on clumps of algae.

The green colouration comes directly from its food – a leaf sheep retains the algae’s chloroplasts (tiny cellular structures that harness the Sun’s energy to make sugars), and incorporates them into its skin, where they continue to photosynthesise. This trick of stealing chloroplasts, called ‘kleptoplasty’, stops the leaf sheep from starving when there’s no food around. It’s one of a range of weird and unique survival techniques that sea slugs have evolved.

The term ‘sea slug’ is applied to an assorted and flamboyant bunch of molluscs, all close relatives of snails that evolved a shell-free adult life. They are found almost anywhere in the sea, from rock pools to the deep sea, in tropical and temperate waters, and even in the Arctic and Antarctica.

Leaf gilled sea slug (Cyerce nigricans)

Sea slugs come in an amazing variety of colours and shapes. “The geometric beauty of them is startling,” says Heather Buttivant, author of Rock Pool: Extraordinary Encounters Between The Tides, and an expert in finding sea slugs around the British coast.

Many, including this tropical sea slug (Cyerce nigricans), are covered in projections called ‘cerata’. When this species gets disturbed, perhaps by a hungry fish or crab, it jettisons some of its cerata, like a lizard dropping its tail, to distract the intruder, while it makes its escape.

Sea slugs follow chemical trails to find food and mates, ‘tasting’ the water with a pair of organs called ‘rhinophores’ that are located on their head. In this species, the rhinophores are forked like a snake’s tongue, to help detect the direction a smell is coming from.

Banana sea slug (Notodoris minor)

With no external shells to hide inside, sea slugs have evolved various ways to avoid getting eaten. The banana sea slug (Notodoris minor) is a coral reef-dweller, and its gaudy colour is camouflage: when crawling across a yellow sea sponge – its preferred food – it becomes hard to spot.

On the other hand, the eye-catching patterns of many sea slugs warn predators to leave them alone because their bodies are filled with noxious chemicals. Some sea slugs produce toxins themselves; others obtain them from their food.

The banana sea slug belongs to a group of sea slugs, the dorids, which have a smooth outer layer and feathery gills sticking up from their backs. A second group, the aeolids, are slim and covered in finger-like cerata that act as gills. Dorids and aeolids are known as nudibranchs, meaning ‘naked gill’.

Lined Nembrotha (Nembrotha lineolata)

Sea slugs are what’s known as ‘simultaneous hermaphrodites’. Each individual has female and male sex organs, but they can’t mate with themselves and have to swap sperm with another slug. The sea slug penis, shown in this close-up of a pair of mating sea slugs (Nembrotha lineolata), is located on the right side of the head, a hangover from the asymmetrical, twisted bodies of the coiling snails they evolved from.

Sea slug copulation can take anything from a few seconds to 10 minutes. Some species mate repeatedly using disposable penises: the first time a pair mates, each slug detaches its penis and within 24 hours grows a new one, subsequently mating a second time. Scientists think the first penis acts as a syringe, removing any sperm left by competitors that the slug previously mated with. A backup penis is coiled up inside both sea slugs, ready to be deployed.

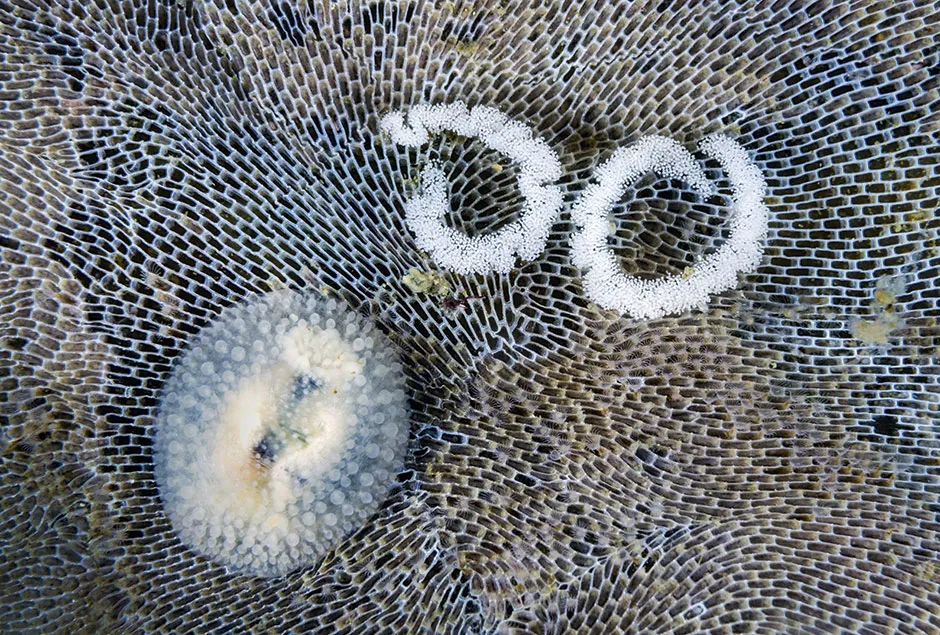

Risbecia tryoni and Knoutsodonta jannae

After they’ve mated, sea slugs lay eggs. Some species lay a few at a time, while others lay thousands or millions, often in spiralling ribbons, like Risbecia tryoni (above), or sometimes in separate clutches, as Knoutsodonta jannae has done here (below).

For sea slug spotters, the eggs can be the best way to find tiny and otherwise inconspicuous species. “They lay coils of spawn that are several times their own body size,” says Buttivant.

The eggs can take a few days or weeks to hatch, either as mini sea slugs or more often as swimming larvae, called ‘veligers’, which have a tiny coiling shell. The veligers swim around until eventually, often triggered by chemicals wafting from their preferred food such as sponges, the larvae will abandon their shells, settle onto the seabed and transform into adult sea slugs.

Flabellina nobilis

This sea slug (Flabellina nobilis) from the North Atlantic is feeding on the stinging tentacle of a flower-like hydroid (a relative of corals and jellyfish) without getting stung.

Its mouth, throat and stomach are lined with the tough material chitin, and it also produces slime which stops the stinging cells from firing. The sea slug keeps the hydroid’s unfired stings, which are like minute poison-tipped harpoons, and pushes them into sacs in its skin to use in its own defence against predators.

“Sea slugs look so delicate,” says Buttivant, “but they actually have all sorts of defences.” One species of sea slug that lives on British coasts will squirt sulphuric acid from its skin when attacked.

Lion’s mane nudibranch (Melibe leonine)

The lion’s mane nudibranch (Melibe leonine), is a sea slug like no other. Living in the kelp forests off the Pacific coast of North America, it has a spectacular, tentacle-fringed hood. To hunt, it grasps kelp fronds and sweeps its hood from side to side.

When a tiny, planktonic animal swims past and touches the tentacles, the hood quickly closes and traps the prey. Lion’s mane nudibranchs have a sweet smell, like watermelons, which deters predators and attracts mates.

Another species of plankton-eating sea slug (not shown) uses hydroids to help it hunt. It scoffs the hydroid, along with the plankton that the hydroid has just eaten – essentially getting two meals for the price of one.