The idea that new, large animal species might be hiding in the world’s wilder places has always been one of the most romantic and appealing of scientific concepts. Even today, it remains possible that a few big mammals, fish or reptiles await discovery in the forests of New Guinea or Southeast Asia, or in certain deep-sea basins. But can we take seriously the possibility, endorsed by a handful of die-hards and believers, that Loch Ness, Scotland’s largest and most famous lake, is home to a new species of gigantic, dragon-like animal more than 10 metres long?

In May 2018, geneticist Prof Neil Gemmell of the University of Otago, New Zealand, embarked on a project to collect and test genetic traces of animals from the loch, and hoped to resolve the enigma of Loch Ness once and for all. He and his team were set to use a technique not previously used on the loch’s water. They were going to hunt for environmental DNA, or eDNA (see below).

Read more about ancient beasts:

- 10 greatest ever beasts

- 17 of the weirdest dinosaurs to walk the planet

- What killed the Ice Age giants?

Are you there, Nessie?

Most scientists do not think there is a monster in the lake. This bold proclamation isn’t due to arrogant elitism or an inability or unwillingness to examine the data that exists, but to the fact that the evidence put forward to support Nessie’s reality has failed to be persuasive.

The photos and films are fakes, hoaxes, or misinterpretations of known objects. Biological evidence that might support the creature’s existence – bones, carcasses, feeding signs or droppings – is non-existent. And the large number of eyewitness anecdotes provides nothing robust or consistent.

Rather than monsters, there are instead assorted references to all kinds of things seen on the loch, like swimming deer, birds, seals, waves and wakes. Few of these things are familiar to the average loch-side visitor.

A psychological phenomenon known as ‘expectant attention’ is also important in influencing people’s experiences at Loch Ness. It explains how people’s observations fit an existing expectation, in this case, that they will see a large, water-dwelling monster.

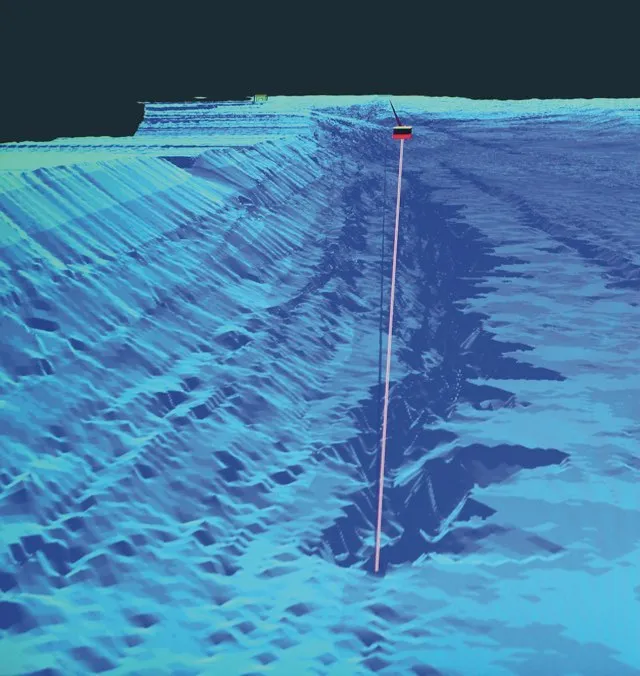

Still, the idea of something mysterious in the lake has nonetheless captured the attention of scientists. Therefore, the water has been swept by vessels emitting sonar, and its depths have been explored by divers, submersibles and motion-detecting cameras.

At least a few authors and scientists have gone on record to state their confident belief in the monster’s existence, the data that convinced them later proving inadequate or erroneous. In other words: science has searched for Nessie, and the results have come back negative.

Listen to our interview with Professor Neil Gemmell in the Science Focus Podcast

In the 2016 book Hunting Monsters, I noted that the ability of scientists to search for and analyse the genetic material that living things leave in their environment – so-called environmental DNA, or eDNA – might provide the ultimate arbiter of the presence or absence of a mystery creature in the loch.

Gemmell was inspired. “I was thinking how we might use eDNA to search for and identify creatures that live in areas hard to investigate using traditional approaches, such as deep oceans and subterranean water systems. Loch Ness seemed a perfect fit for that sort of project,” he says. “I’m not a Nessie believer, but I’m open to the idea that I might be wrong.

This project is about understanding the biodiversity of Loch Ness, with the added bonus being that we might find evidence of something new that may explain the monster legend.” According to Gemmell, the study could also have benefits for our understanding of the health of Loch Ness and its future management.

Species search

The study of eDNA has proved an invaluable tool to biologists ever since it was devised in the 1990s. It has been used to examine the distribution of species no longer present in an area, but whose genetic traces are still preserved in sediment.

It has also proved crucial in tracking the spread of invasive species. Asian grass carp in the North American Great Lakes and the New Zealand mud snail in the western USA, to use just two examples, have both had their progress monitored via eDNA.

eDNA studies have also been used in the search for species that are rarely seen by people and, in some cases, not seen at all. A 2012 study of seawater from the Baltic confirmed the presence of long-finned pilot whales in the area, a species not seen by people during the period covered by the study and generally thought to be an extremely rare visitor there.

More remarkable is a 2018 study concerning eDNA collected from the marine waters of the New Caledonian archipelago in the southwest Pacific. This revealed the presence of six shark species that were not picked up at all via more conventional sampling techniques, like long-term observation and the use of baited locations set with automatic cameras.

It’s doubtful that any of the scientists involved in these various eDNA projects ever considered how applicable this work might be to the search for lake monsters, but it’s with this record of eDNA-based successes in mind that Gemmell announced his plans to collect and analyse eDNA from Loch Ness.

Hot on Nessie's h-eels

So what did prof Gemmell and his team discover when they searched beneath Scotland’s most famous loch? Unfortunatley for Nessie-hunters and conspiracy theorists, the eDNA census of the loch did not reveal the presence of a large animal matching the ‘monster’.

“We can't find any evidence of a creature that's remotely related to [a Jurassic-age reptile] in our environmental-DNA sequence data,” Gemmell said to the media in today. “So, sorry, I don’t think the plesiosaur idea holds up based on the data that we have obtained.”

However, the study did discover many additional species living there, including the possibility of one aquatic giant.

“There is a very significant amount of eel DNA. Eels are very plentiful in Loch Ness, with eel DNA found at pretty much every location sampled – there are a lot of them. So - are they giant eels? Well, our data doesn’t reveal their size, but the sheer quantity of the material says that we can't discount the possibility that there may be giant eels in Loch Ness.

“Therefore we can’t discount the possibility that what people see and believe is the Loch Ness Monster might be a giant eel.”

Nobody really expected to discover evidence for a creature that might be regarded as similar to the ‘Loch Ness Monster’ of popular lore. But the study will help us to understand the biology and ecology of Loch Ness and its surrounding lochs and lakes.

“We came here to study environmental DNA, and our analysis has captured everything we thought is in the loch. We now have an excellent database which if compared to any future testing could enable us to identify trends and changes in the Loch environment. That is essentially the benefit of eDNA – it is an extremely powerful and robust tool to document the living things (both large and microscopic) present in a given place. It’s going to be extremely useful in the future as the technology becomes quicker and more accessible, more data is created.”

If eDNA and questions about a monster can help us to investigate this subject and learn more about the natural world and how it functions, then this study has already proved a most worthwhile endeavour.

This feature is adapted from an article previously published in the December 2018 issue of BBC Science Focus - subscribe here.

What is eDNA?

DNA extracted from an organism can reveal a great deal about its relatedness to other living things, both in the small-scale sense of how it compares with other populations within its species, and in the broader sense of where it fits within the tree of life.

But if it only takes a tiny sample of organic tissue – a single skin or gut cell, for example – for DNA to be extracted, then could DNA-retrieval techniques be sophisticated enough for us to collect DNA that living things leave in their environments, via their shed cells, urine and faeces?

The answer is yes. In a series of studies that first appeared in print during the 1990s, ecologists and geneticists worldwide have shown how the presence and identity of organisms in an area can be extracted from soil, groundwater, ice, freshwater and seawater via so-called environmental DNA or eDNA.

By collecting water from Loch Ness, scientist Prof Neil Gemmell and his team hope that they have obtained eDNA from the loch environment. They have also taken samples from nearby lochs to analyse their eDNA too.

Back in the laboratory, the samples will be analysed, and any eDNA will be identified and extracted. The samples are then profiled and compared to those already in genetic databanks. Many species already known to be present in the loch will be identified in this way. The hope is that species new to the area, and perhaps even new to science, will be discovered as well.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard