Back in 2010, we took a look into our crystal ball at what life would be like in the distant future, in the year 2020. The time has come to dig up this time capsule and see how well we did.

We asked science writer Luis Villazon to map out the average day of someone living in the year 2020. Here's what he came up with.

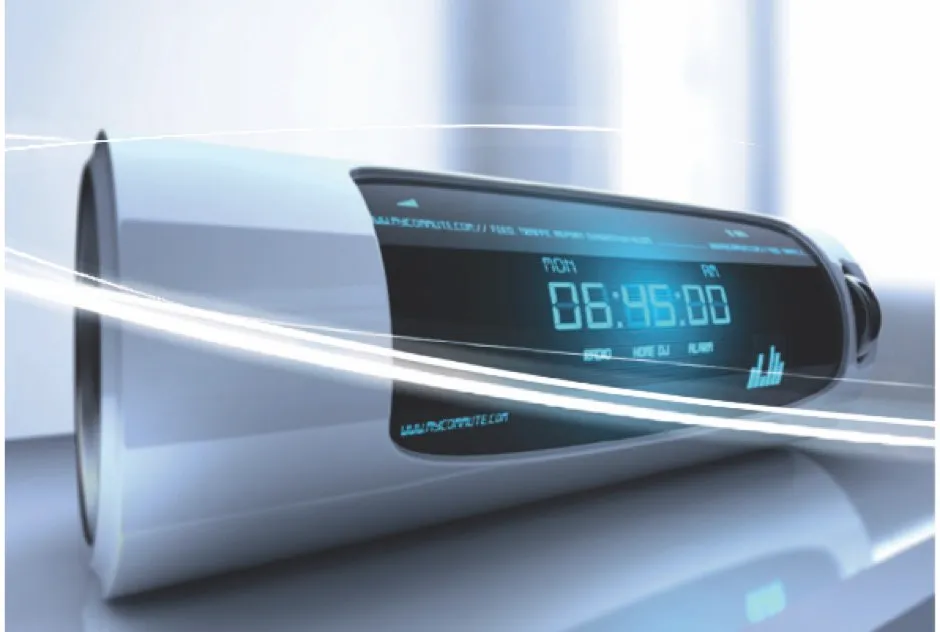

06:45

The alarm clock goes off. It’s notionally set for 07:00, but the clock’s connected to the internet and has woken you 15 minutes earlier than usual because the traffic reports from www.mycommute.com are predicting longer delays today due to a tube strike.

The internet radio station streams music from a standardised station playlist, but the HomeDJ service means that the news, traffic and weather are local, and are customised for the level of detail you want using the preferences that you set on their website. The info is dropped seamlessly into the programme between songs.

When you leave the house, you can carry on listening through the internet radio in the car. GPS data automatically selects the most relevant traffic news stream for you and updates your sat-nav.

The future of radio

Internet radio is becoming increasingly important, offering the ability to customise what you listen to. The trend towards radio over internet has already started – US market research company Edison Research says that, between 2007 and 2008, the number of people listening to radio over the net increased from 12 to 20 per cent.

Services like Last.fm give an insight into internet radio’s potential. It offers personalised ‘radio stations’ – uninterrupted streams of music based on your taste.

It's not just at home we’ll be listening to internet radio. At the 2009 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, German audio manufacturer Blaupunkt and audio streaming company miRoamer showed off the first internet car radio.

07:15

For breakfast, you leave the bespoke smoothie maker in the cupboard. Using inkjet technology to add a customised mix of micronutrients to your drink was the diet fad of 2017, but the company went spectacularly bust after a few high-profile vitamin A poisoning cases and you can’t buy the cartridges any more.

Instead it’s just toast, plus an apple that’s been stored in a FrootStore bag. This is a plastic bag you can buy from a supermarket that’s impregnated with a compound that inhibits ethylene – the naturally produced gas compound that encourages fruit to ripen.

The FrootStore holds everything from your apples to avocados in their pre-ripe condition until the time you want to eat them. When you do, you take them out of the preserving FrootStore bag and place them in a FrootRipe bag, which emits ethylene for a few hours.

Home-ripened fruit is a bit cheaper to buy because it reduces wastage at the supermarket, and it means every apple is in perfect condition when you sink your teeth into it.

The apple core and the coffee grounds all go in the back door composter. By opting for a two-thirds size wheelie bin, you have saved 20 per cent on your council tax bill, but there’s no room for anything even remotely biodegradable in there.

The future of food

Food storage could change radically over coming years. There’s already been a change within the large-scale food storage industry. Historically, temperature has been used to keep food fresh and stop it ripening too early. Now science is taking over.

Fruit are encouraged to ripen by ethylene, but a compound called 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) has been shown to stop fruit from responding to ethylene – delaying the ripening process. So apples and pears are now stored in a 1-MCP-rich environment.

And it’s perfectly feasible for this technology to be downscaled so it can be used in the home. “You would just buy a roll of bags impregnated with something like 1-MCP that would cause the fruit to be long lasting,” says Greg Tucker, professor of plant biochemistry at the University of Nottingham. “Then you could put it in a ripening bag containing ethylene.

07:50

Your journey to work is still by car – the public transport infrastructure hasn’t improved much in the last 10 years. It’s now almost impossible to buy a new car that isn’t at least a hybrid, uses regenerative braking (which charges a battery as you brake) and smart idling (which cuts the engine if you stop for more than a few seconds).

Service stations now have fast-charge points at some locations where you can leave your car recharging while you have a coffee. That said, most cars on the road still run on petrol or diesel only – simply because there are still a lot of old cars. Rumour has it that petrol could soon break the £1.50 per litre barrier.

The future of driving

The hybrid car revolution started with the Toyota Prius in 1997. And all the signs are that this revolution, which has been slow to gain momentum so far, will gather pace. Exactly how much pace is a subject of debate, though.

Mark Z Jacobson, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University, thinks there will be a rapid change, “I believe that within five years a majority of new cars will be pure electric or plug-in hybrid.” Other estimates are a little more conservative. A report published in 2009 by market research company RNCOS says 35 per cent of new cars made in 2025 will be electric – 25 per cent being hybrids and the rest purely electric.

One of the main practical problems with current electric cars is the time it takes to recharge them. But research is already taking place that could slash charging times. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s elEVen project, for instance, which started last year, has a target of less than 11 minutes for a recharge.

As for petrol and diesel prices, it seems that the only way is up. A 2008 report by financial services firm Goldman Sachs says oil prices could reach $200 a barrel in the next 10 years, which translates to £1.46 a litre for petrol at the pump – a 35 per cent increase on today’s prices.

Our love of cars isn’t likely to end soon. A 2008 RAC report states there is now nearly one car in the UK for everyone with a driving licence, and predicts that the number of cars will grow by 30 per cent by 2020.

09:00

Fewer people spend all their working day in an office now. Lots of companies that outsourced their call centres overseas have brought them back to the UK as distributed Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) systems. Here, calls are routed to individual operators spread around the country, via internet data lines. This allows more of us to work from home, with flexible working hours and correspondingly lower pay.

Large companies do still keep conference rooms for board meetings and client presentations, but the days of the private office for middle and upper management are largely over. Those of us who don’t work from home, hot desk.

You’ve driven into town today for a meeting with your project team at a coffee shop. This one is popular with the corporate world because of its clever use of acoustic materials that make the music loud in the public areas but much quieter in the discrete booths around the sides. This makes it easier to talk in the booths, and hard to eavesdrop on confidential discussions from the rest of the shop.

The future of work

We’ve already started migrating out of the office and into the study at home. According to figures from the Office for National Statistics, 3.1 million people in the UK worked mainly from home in 2005 – up from 2.3 million in 1997.

And business use of VoIP is growing too – according to technology research company Ovum, 20 per cent of companies in the UK have already adopted it. With VoIP your phone calls are carried out over internet connections rather than the telephone networks – and it’s typically far cheaper.

The café could become an increasingly important part of our working lives. “Coffee houses already provide a workplace environment, but they don’t provide privacy,” says BT futurologist Lesley Gavin. “At the moment you can do it with high-backed chairs, but by 2020 you might have a noise-cancellation type environment over one area of the coffee space.”

15:00

You spend the afternoon trying to get hold of a copy of a controversial biography of the Chinese premier. Hard copies of the book are banned outright in China and the electronic version you downloaded to your e-book reader is refusing to play; it just displays a ‘Content is blocked in this locale’ error.

The web filter in the coffee shop’s Wi-Fi connection is even blocking internet forums that are discussing this latest example of net censorship. Eventually you manage to send a carefully worded email that makes it past the filters to a colleague in Finland who sends you a link to a file-sharing site that might work – once you get home, at least.

The future of the internet

China’s record on net censorship is well known. As its economy grows in prominence, this censorship is likely to become more pervasive, and the form of censorship used is likely to evolve. “The biggest changes in net filtering will be at the application level,” says Jonathan Zittrain, professor of law at Harvard Law School and a co-founder of its Berkman Centre for Internet and Society.

“A regulator might ask that a particular document be removed from a Kindle or other e-book reader – which is a new category for filtering, since e-book readers and other internet-aware specialised devices are still so new.”

17:00

On the way home you stop at a chemist’s shop to pick up a FluCheck. This looks like a home pregnancy tester, but instead of urinating on the stick, you use it to swab the inside of your nose. The one-use device then detects the presence of antigens on the surface of the flu virus particles.

It takes 20 minutes for the lab-on-a-chip to generate a result, so if you swab yourself on the way out of the shop, you’ll have an answer by the time you get home. FluCheck costs £9.99, which is pretty cheap to discover whether you have actual flu or just man-flu.

But if you buy one every time you feel run down, it soon adds up – and that’s without considering the one-use tests for prostate cancer, hepatitis, TB and diabetes. The ‘worried well’ are big business these days.

The future of health

Super-fast diagnoses for a variety of conditions are almost here. Currently, diagnosing something like swine flu requires a sample to be sent off to a lab, with the results taking hours or even days. ‘Lab on a chip’ technology, where tests are carried out on a mini lab the size of a computer chip, is a thriving area of medical research, promising portable testing devices.

Ostendum, for instance, a spin-off company of the University of Twente in the Netherlands, has developed several prototype health detectors, and expects to have one on sale by the end of this year. It can detect viruses and bacteria from saliva or any other body fluid.

18:30

All the checkouts at your local supermarket are self-service, apart from a single ‘assisted checkout’, intended for customers with disabilities and staffed on demand. There are still several chains that offer staffed checkouts, and claiming to hate the automated desks is now as British as complaining about the weather.

But no-one complains about the prices. Most food manufacturers now label their products with food miles and some have gone a step further with a ‘carbon foodprint’ – the total carbon emitted during the production process, not just transportation.

The future of shopping

2009 marked a watershed in the British supermarket industry with the opening of the first completely self-service store – the Tesco Express in Northampton. Industry analysts expect self-service to grow in prominence. Consultancy Retail Banking Research predicts that even by 2011, there will be 15,000 self-service checkouts across the UK compared to the current 7000.

18:45

Dinner is Bosnian meatballs with ‘Kljukuša’ (a sort of baked hash brown) because Jamie Oliver – now in his mid-40s – is touring Central Europe for his latest video podcast series. Several broadcasters now transmit programmes simultaneously through the aerial and over the internet. Commercial TV revenues continue to slide – fewer people are prepared to sit through live adverts now.

The future of TV

On-demand TV over the internet is the broadcasting revolution of the moment. The number of videos watched online in the UK increased by 47 per cent between April 2008 and April 2009, according to figures from internet research company comScore.

And the line between the internet and your telly is already blurring. Samsung has signed a deal to provide bits of the web to its internet-connected TVs. So in a few years, watching something from the net will be even simpler – fuelling the explosion in internet video. No more sitting at a desk to watch YouTube.

19:30

While you eat dinner, you check your LifeSaver account. This contains all the audio and video you uploaded at a few points during the day, recorded by a tiny camera built into your glasses. LifeSaver picks out the most significant moments and sends out a video stream to everyone who has signed up to receive them.

Sir Stephen Fry MBE has three hours of LifeSaver video for today but you don’t have time to watch all of it tonight. You’ll catch the weekly summary on the Celebrity LifePeeks website. But there’s time to catch up on today’s news headlines on your e-reader.

The future of memories

The first step towards ‘LifeSaver’ is having a means to record your day. “The camera could be in a badge or your glasses,” says BT futurologist Lesley Gavin, “with the data collected on the device or networked.”

Even by 2020, mobile network technology is still unlikely to be sufficiently advanced to allow networking like this. Instead, the data would be recorded on the device for you to upload periodically. “It’s not going to be 80 per cent of us doing this by 2020, it will be the early adopters,” says Gavin.

Next it’s a question of editing your most significant moments during the day, so they can be fed out as video posts. “If you have software that can spot someone smiling at you, for instance, it could suggest that clip as it’s likely to be something that’s significant,” says Gavin.

“Or it could spot something that’s fast moving or something that you stare at for a long time. The rudiments of this are here today, it has just not been put together into a product.”

23:00

Your iPillow triggers as you get into bed with the next chapter in your current audiobook, played through flat speakers embedded in it. The pillow automatically adjusts the volume based on your activity and posture, and switches to gentle music for a while when it senses you are nearly asleep.

23:30

Through the night, while you’re asleep and electricity demand is low, wind and wave power continue to supply electricity to the grid. Some of this is used to pump water back up into the storage reservoirs in the recently completed hydroelectric power stations in Scotland’s Great Glen.

Tomorrow morning, this water will flow back downhill and feed electricity into the National Grid when everyone switches on their kettles and toasters. These hydroelectric plants are the first pumped storage schemes built since the 1970s.

Combined with the photovoltaic cells that you put on the roof three years ago, more than 15 per cent of your total electricity now comes from green sources. The smart meter allows you to keep track of your electricity consumption. Long showers and keeping the telly on standby are things of the past.

The future of energy

A government white paper in 2009 announced proposals to invest £120m in offshore wind technology in the next few years, and for every home to have a smart meter by 2020.

It also looks like pumped storage hydroelectric could make something of a comeback. Energy firm Scottish & Southern Energy has announced proposals for two projects in Scotland’s Great Glen. It’s envisaged both schemes would produce 1000GWh of electricity a year to meet peak demand.

- This article was first published in the January 2010 issue of BBC Science Focus Magazine