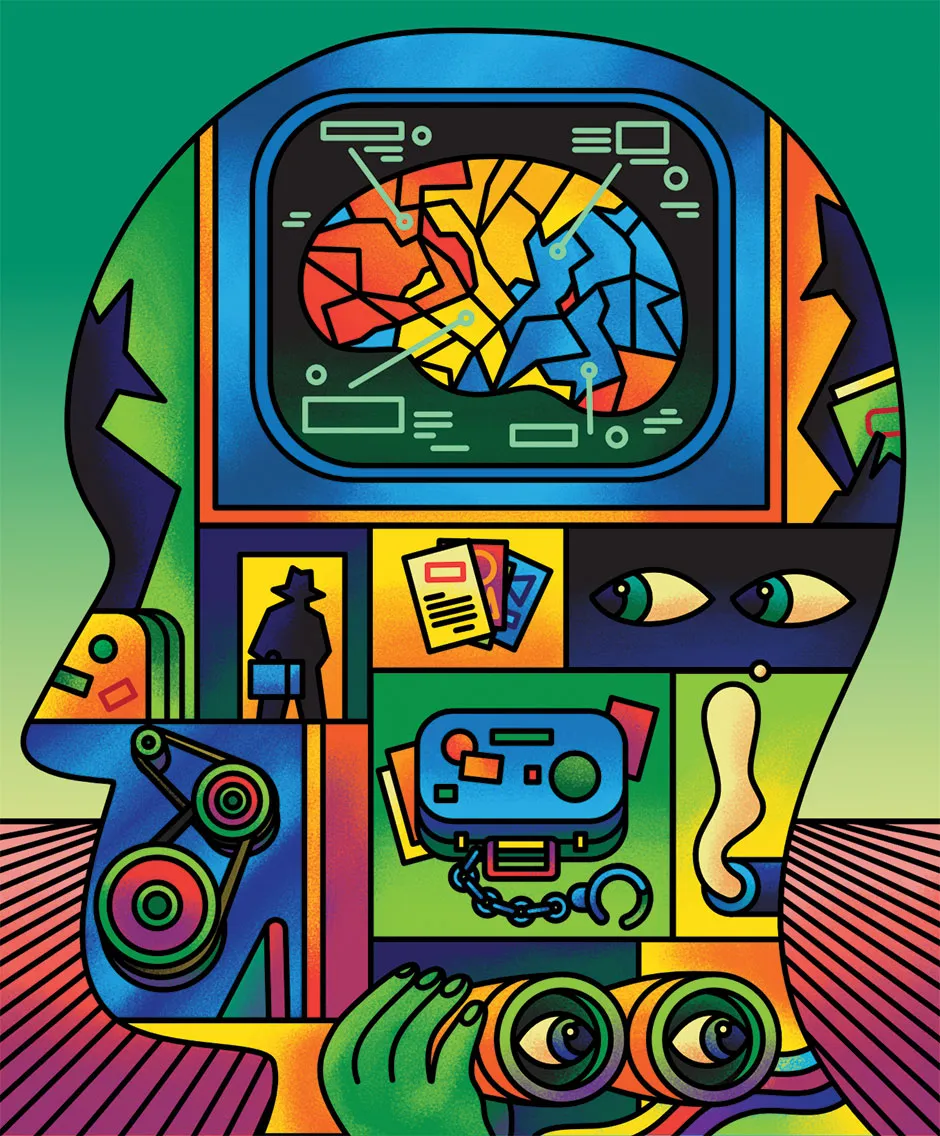

The human brain loves patterns. It’s built to make one and one equal two, and to see inappropriate things in Rorschach tests.

Psychologically speaking, we lean on patterns as a way to make light work of a world of random stimulation. So when things don’t add up, we feel uncertain. Our response is to look for anything to avoid the dissonance of not knowing where we stand.

Welcome to our COVID-19 world. We don’t know what’s going on right now. Nobody does. There are a lot of incredibly smart people doing some hardcore detective work to get to the bottom of this pandemic, but in the meantime, the rest of us are on the receiving end of conflicting messages from all sides.

Read more about psychology:

When it comes to the kind of uncertainty we are trying to comprehend right now, there is literally a war going on inside our heads. In one corner is the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that’s rationally gaming out the possible outcomes.

In the other corner is our amygdala – the bit that controls fight or flight – and it is sprinting towards anything that feels right, and away from anything that feels threatening. It’s looking for simple solutions. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what we should be avoiding.

Dr Charles Morgan is a professor of national security at the University of New Haven, Connecticut. He has been studying extreme uncertainty for more than four decades, working with active duty special forces soldiers who spend a lot of time in what everyday people would categorise as ‘extreme stress’.

Charles – or Andy as he’s known to anyone except his mum – is an affable chap with an interest in what makes our brain chemistry tick.

According to a 2013 paper from Andy and his colleagues at Yale, the US Navy and the University of California, we’re more likely to believe (and in the age of social media: rapidly spread) things that are untrue.

What’s happening, he thinks, is that exposure to high states of anxiety and stress make it easier to create a false memory. Our critical thinking drops out. We become dominated by the primitive amygdala, which bypasses misinformation past our prefrontal cortex and fills in whatever gap doesn’t make sense in our internal story.

Read more from Aleks Krotoski:

- Hitting the wall: Can you change your mindset to endure lockdown more successfully?

- A learning curve: despite school closures, our children will be OK

- Corrupted Blood: what the virus that took down World of Warcraft can tell us about coronavirus

Think about it: if you are looking for a pattern, a conspiracy theory is like a box of free sweeties. Our brains would prefer to think some evil person out there is doing all this, because it means that someone is actually in charge. And that makes us feel better. Because stuff isn’t random any more. And now we know who to blame.

How do we tame the amygdala? We invoke the adult part of our brains to tame the impulsive child. And to do that, we need to create routine. We administer self-care.

We start on the path that leads us to understand that the control we think we have over our world is a facade. This pandemic is an opportunity to reassess where we stand.