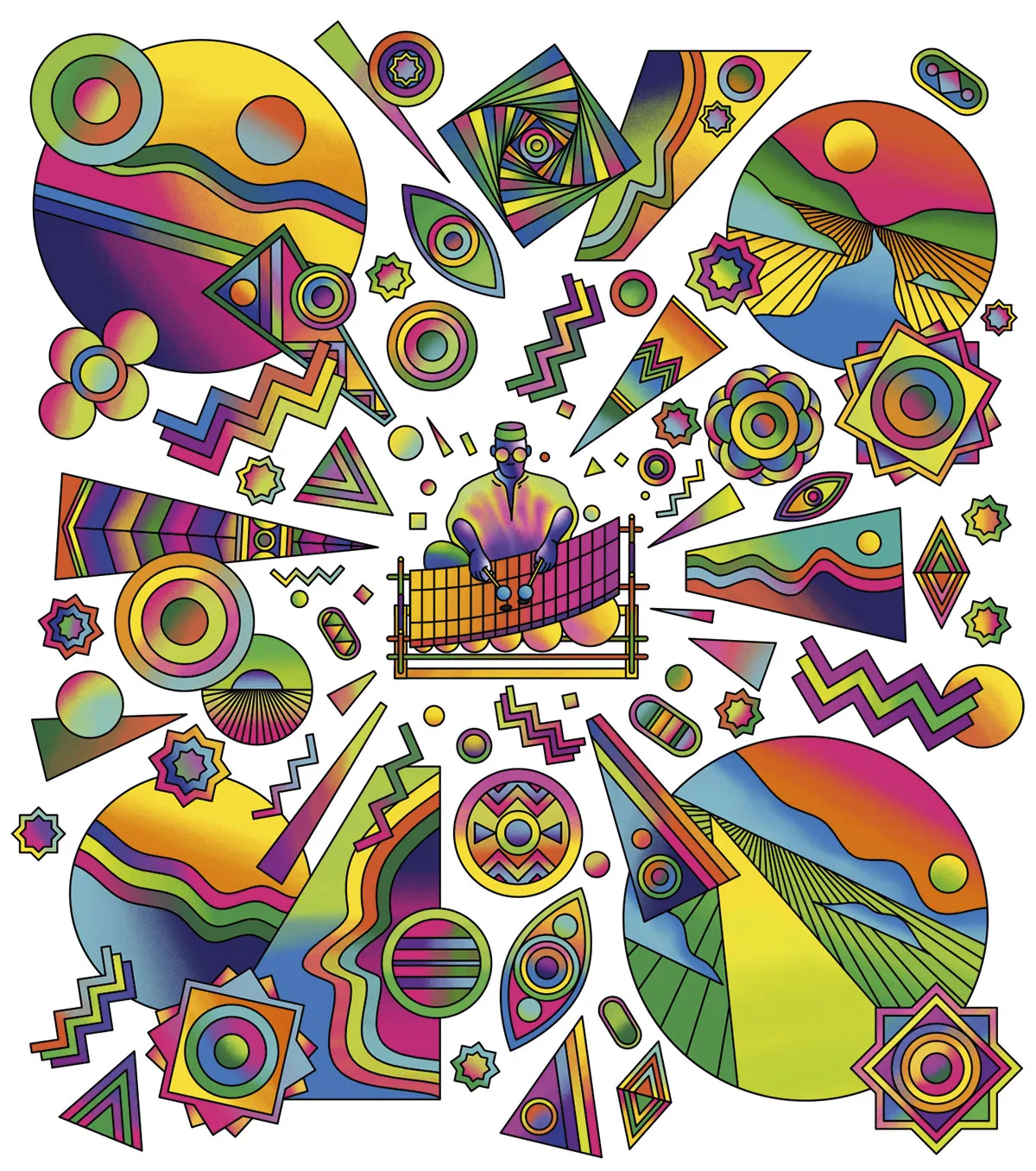

Once a year in a small village deep in the mountains of Mali, members of the Mande community gather around the world’s oldest balafon to hear the folk stories of their traditions. The sacred instrument, known as the Sosso Bala, is made of wood and looks like a xylophone. It transmits traditions from the 13th Century that keep this distributed community tethered together through space and time.

The man playing and singing is a direct descendant of the original storyteller and king. He holds all the knowledge of their world and its history: a one-stop shop for everything to do with the Mande people.

Most of us don’t have a musical instrument that ties us together, but we will have someone in our lives who’s the keeper of the knowledge. Often it’s a matriarch – a grandmother, a mother, a great aunt – who, out of interest or a sense of responsibility, keeps all our stories ready to tell upon request.

The stuff in their heads is amazing. Who did what to whom and when, possibly the reasons why, where and certainly how. This is translated from gossip to noble truths, and turns into fables that have cautionary outcomes and actionable points. The ones that are more generic are unfortunately known as ‘old wives’ tales’, a turn of phrase that diminishes their value as good advice throughout the ages.

The stories can be useful for dealing with all sorts of queries: how do I get rid of that stuff between my toes? How do you treat morning sickness? (Often followed by: what’s the best way to get a baby to sleep?) Sometimes they answer bigger questions: where do I come from? What’s my moral compass? The stories provide an answer, but the questions don’t often have a single answer to them. It’s just useful to speak with someone who knows how things are done.

Recently, we discovered that this very human trait isn’t limited to humans. Marine biologists, animal behaviourists and other researchers have documented cultural knowledge in other species; whale pods returning to parts of the sea that they’d abandoned a generation before; monkeys that communicate hunting skills to their offspring. Folk knowledge is not only culture, it’s also survival. This is why we do it.

Mostly we do it in small units. Families sharing around a dinner table, or around a balafon. Recently, folk knowledge has expanded to global networks interconnected by electronic wires. Look at any forum, particularly parenting forums, and you’ll see folk knowledge at work and at play. It’s exploded as we’re trained to look for information online, rather than from within.

In this global folk wisdom experiment, what seems to have happened is that our questions can be more easily answered with misinformation. There are, after all, as many big questions seeking wisdom as small ones seeking solutions.

We don’t gather once a year to reality check our folk stories. The Mande do, and their folk traditions, bounded by their culture and their practices, are realigned around a musical instrument. The internet has no reality except its own and, left unchecked, its wisdom has no rhythm. It’s just chaos.

- This article first appeared inissue 369ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here

Read more from Aleks Krotoski: