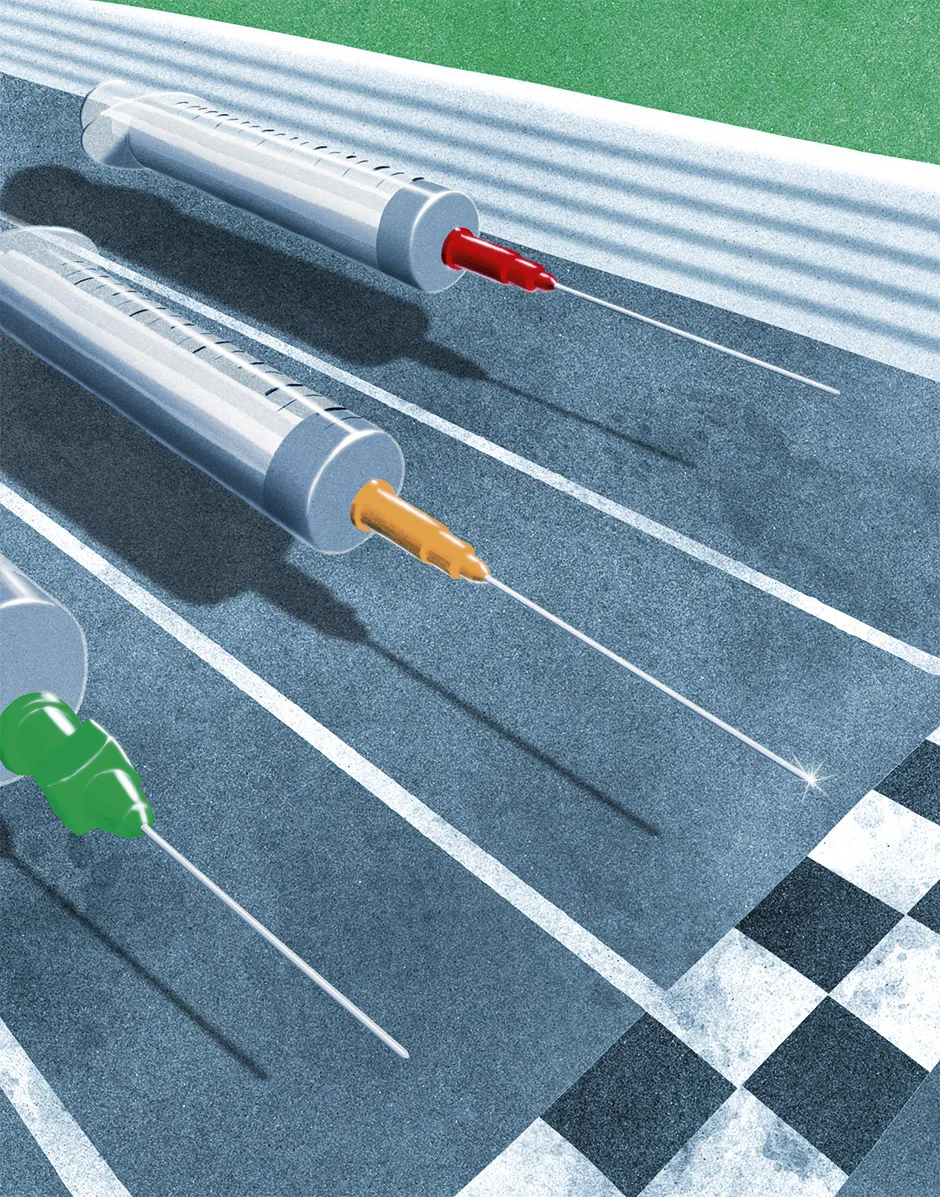

Just as 2020 was the year of COVID, I expect 2021 to be the year of the COVID vaccine, as the race to develop a vaccine has been truly extraordinary.

In March 2020, I was lucky enough to be making a Horizon programme all about COVID-19 when I managed to get an interview with Prof Robin Shattock, who heads the Department of Infectious Disease at Imperial College. When we spoke, he and his team were well underway developing their own novel coronavirus vaccine.

Shattock, unlike many other experts I spoke to at the time, was optimistic that a vaccine could be developed, tested and produced in quantity by the end of 2020.

More traditional vaccines involve growing whole viruses, and you make your vaccine from killed or weakened versions of them. But Shattock’s vaccine is based on mRNA, the molecule that your cells use to create specific proteins. This is the same approach used by the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

The new vaccines are based on injecting mRNA that specifically produces the coronavirus’s ‘spikes’, not the whole virus. The idea is that these spikes will provoke an immune response, in the same way the real virus would, but without the resultant infection.

Unlike the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the Imperial one is self-amplifying, meaning that it should go on provoking an immune response for longer. It also means we should need far less for a single dose and it could, potentially, be much less expensive.

As Shattock said at the time, although he was concerned about potential side effects, he expected them to be less of a problem with this approach than with a standard vaccine. “Remember, we’re not growing whole viruses and we’re not using cells or animal material,” he told me. “The vaccine is an extremely pure product. That’s one of reasons we think the risk of side effects is very low.”

Read more from Michael Mosley:

- Dr Michael Mosley on how to manage seasonal affective disorder

- Dr Michael Mosley on how to get even more from your daily walks

Another concern some people have is that this novel coronavirus could mutate, like the flu and HIV, making the vaccine useless. Having worked for years on HIV vaccines, Shattock is well aware of the challenges. But, unlike AIDS, the virus that causes COVID-19 isn’t mutating fast.

“There is never any guarantee that things will work, but we know that as a target this is much easier than some of the vaccines we’ve been trying to make because it’s a relatively stable target to go after,” he told me. “So we think there’s a very high scientific probability that a vaccine will work and go on working.”

He seems to have been right, on all counts, and though the Imperial vaccine has yet to complete full clinical trials, I expect that, like other COVID vaccines, it’ll be available in 2021. By then we should have a range of vaccines to choose from and a brand new approach to vaccination, based on mRNA technology, which will transform this branch of medicine.

- This article first appeared inissue 358ofBBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here