Remove humans from the driving equation and cars will be safer. That’s the thinking behind the push for autonomous vehicles – and the reason why, like it or not, they’re coming to our roads.

“Autonomous vehicles reduce the risk of collisions, and that’s recognised by insurers,” says Ian Crowder from the Automobile Association (AA). “If the technology proves to be much more reliable than humans, who can be subject to tiredness, stress or distraction… there’s every possibility that situations that would typically lead to collisions will be removed.”

Safer cars and safer roads are attractive prospects, in both human and financial terms. According to the Department of Transport and the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, the intelligent mobility market is estimated to be worth £900bn annually globally by 2025. This is why car manufacturers are pushing to develop the vehicles, and why the UK government is investing heavily to help them. In 2016, £39m of a £100m fund was awarded to projects working on enhanced communication systems between vehicles and roadside infrastructure, and trials ofautonomous vehiclesin Greenwich, Bristol and Milton Keynes.

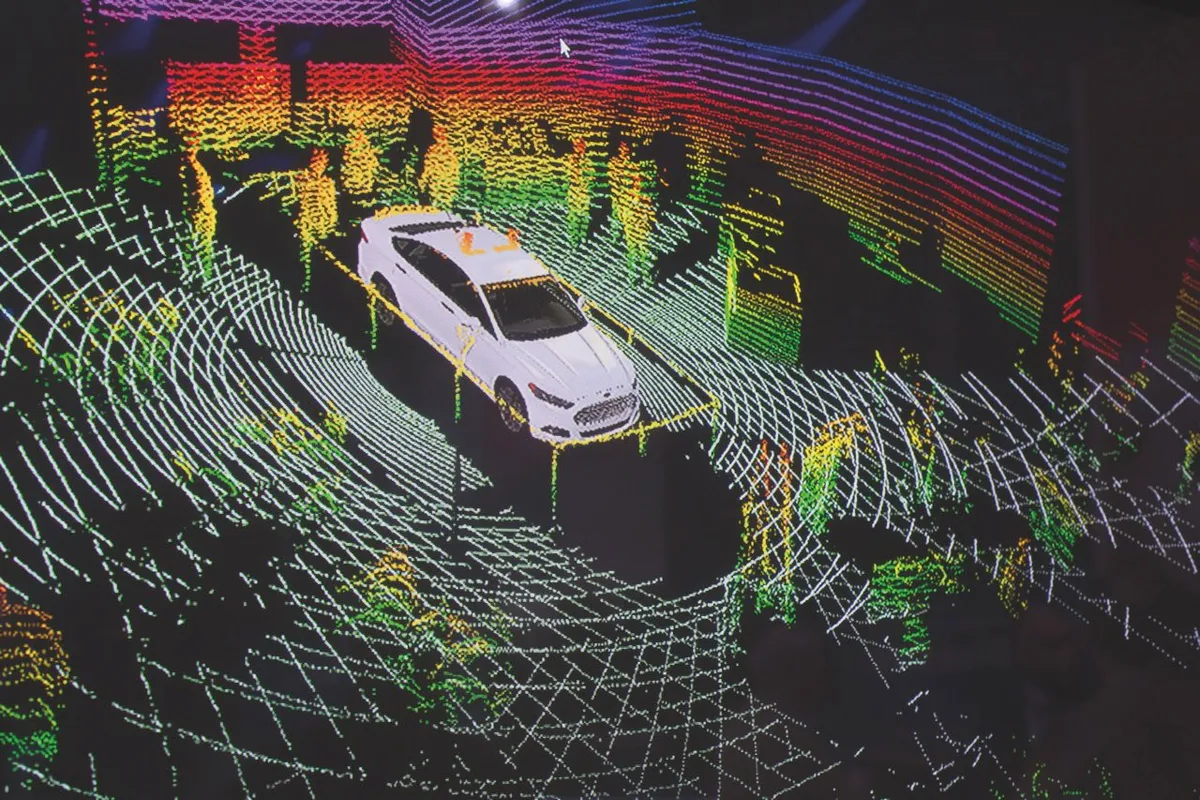

But what’s controlling these cars if there’s nobody at the wheel? The short answer is a lot of extremely sophisticated technology. Audi, the first manufacturer to receive permits to test autonomous vehicles on public roads (in Nevada in 2013 and Florida in 2014), uses differential GPS (said to be accurate to within a few centimetres), 12 radar sensors (to scan the road in front of the car), four video cameras (to spot road markings, pedestrians, objects and other vehicles), a laser scanner (that emits nearly 100,000 infrared light pulses per second, covering a zone of 145° on four levels around the car to profile its surroundings) and a powerful computer to process everything the sensors detect. And all of those systems need to work together so that the car always knows where it is, where it’s going and what’s around it.

Are self driving cars dangerous?

Some of these systems have been shown to work, and have found their way into cars with adaptive cruise control or parking assist. But relying on them to safely conduct a journey on open roads alone is a big step. Still, it’s a step that many companies including Tesla, Google, Fiat Chrysler, Renault-Nissan and Uber (with the help ofVolvo) are in the process of taking. Although their efforts have, on the whole, been safer than normal cars (in terms of the number of accidents per miles driven), they have encountered problems. For example, in 2016 Renault-Nissan’s then-CEO Carlos Ghosn admitted to CNBC that the system in its vehicles is confused by cyclists “because sometimes they behave like pedestrians, and sometimes they behave like cars”.

Meanwhile, the cameras on Tesla’s vehicles have been said to struggle with the glare from sunshine, particularly at dawn or dusk. And sunlight’s not the only natural phenomenon that can throw a spanner into the works: rain interferes with what a driverless car ‘sees’ through its cameras, and reduces the effectiveness of any laser scanners, as the drops can bend and reflect the light pulses.

Problems like these have led to some high-profile incidents. In December 2016, Uber had to withdraw the 16 test vehicles it was trialling in San Francisco after California’s Department of Motor Vehicles revoked the cars’ licences. The local authority said that the ride-hailing company didn’t have a permit to operate autonomous vehicles on the city’s roads, but its decision came after footage emerged of the vehiclesrunning red lightsand veering into cycle lanes. Then in March 2017, Uber temporarilysuspended its self-driving programmeafter one of its cars flipped onto its side in a crash in Tempe, Arizona.

Perhaps the most notable failure happened in May 2016, when a Tesla Model S running in Autopilotcrashed into a truckin Florida, killing driver Joshua Brown. Tesla told investigators that the Autopilot was not at fault, but there had been a “technical failure” of the automatic braking system.

Autonomous cars on test

Failures are to be expected during the testing and developmental phases. “It’s only through using the technology and trying it in real life that it’s going to be improved, because even the best developers are not going to recognise every possible scenario that an autonomous vehicle might encounter,” Crowder points out. But given that people’s lives are at stake if an autonomous vehicle fails, perhaps the roads aren’t the best place to test the technology until we can be sure it’s more reliable. Especially when we could put autonomous vehicles through their paces in another way: motor racing.

“In many ways we’re ahead of the industry,” says Justin Cooke, the chief marketing officer of Roborace, the championship for autonomous electric vehicles that’s expected to start in the next few years.

Roborace Highlights | History made on the streets of Paris (YouTube/Roborace)

“Roborace was developed to evolve technology that will be used on the road, and accelerate the speed at which both electric and autonomous technology is being tested for road cars.”

But despite the speed and competition, racing is arguably a less extreme test environment as there are no pedestrians, roadworks, junctions and crossings to worry about, and all of the traffic’s moving in the same direction – albeit very fast. Hence, unlike the autonomous vehicles being trialled on the road, the Roborace cars won’t have someone onboard to take control if something goes wrong. So what happens if a car goes awry during the course of a race?

“All the cars will be equipped with a ‘safe stop’ that the engineers control back in the pit,” explains Cooke. “If the car goes off course for any reason, it can be brought to an immediate stop using this button. In fact, it’s even safer than a human-driven race car, as the robocar can literally stop instantly, because there’s no delay from a human reacting to a problem and then performing an emergency stop.”

The cars’ first competitive public outing in February brought mixed results. Two driverless cars took to the city-centre circuit ahead of the Formula E race in Buenos Aires but only one finished. The other overshot a bend and crashed into the barriers – although, encouragingly, the car that completed the race not only achieved a top speed of 186km/h (116mph) but also successfully avoided a dog that strayed on to the track. Another demo race is scheduled for the cars on 1 April.

When driverless cars go wrong

Roadgoing autonomous vehicles don’t have the luxury of a pit crew, however. Which is why the vehicles being tested on our roads need to have a qualified driver in the driver’s seat ready to take control in case of emergency. It’s a policy that’s likely to be retained if – or more probably when – autonomous vehicles are given the go-ahead, meaning you won’t be able to stumble out of a pub drunk and expect your car to drive you home.

But this approach creates more conundrums: if the ‘driver’ isn’t actually driving, doesn’t that make them a passenger? And if the driver fails to react correctly and has an accident, is it their fault or the car’s? The more cynically minded might see this as a ‘get out of jail free’ card for manufacturers of autonomous vehicles. Uber blamed the instances of its cars running red lights in San Francisco on human error, and there are reports that Joshua Brown was watching a film when hisTeslacrashed.

“It does raise issues for insurers, because you have the transfer of liability if there’s a collision involving a driverless vehicle,” says Crowder. “It’s something that the insurance industry certainly needs to think about, and indeed is thinking about. If it’s a software failure that leads to a collision, there need to be fairly robust procedures in place to ensure that such a claim can be met promptly, and that there are the processes in place to do that.”

The Association of British Insurers is pushing car manufacturers to ensure that autonomous vehicles can collect core data in the event of an accident, and that the information is made available to prevent drivers being unfairly blamed. The data would cover a period from 30 seconds before to 15 seconds after an incident, and provide a GPS record of the time and location of the incident; confirmation of whether the vehicle was in autonomous or manual mode; if, while in autonomous mode, the vehicle was parking or driving; when the vehicle went into autonomous mode, and when the driver last interacted with the system.

Car hacking

But what if someone is controlling the vehicle who isn’t the driver? In other words, what if an autonomous vehicle is hacked? This has already been proven possible with conventional vehicles: cyber security experts Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek have managed to take over various vehicles’ electronic control units remotely.Hackingis therefore an enormous concern for everybody, not just in terms of losing control of the vehicle but also regarding what that vehicle could then be used for, as Crowder points out.

“[Hacking] is a concern and it’s something that’s often raised… it could open the way towards terrorism or other criminal activity. But that’s a risk that’s already there – with cars that have keyless technology, for example. Certainly, the manufacturers will need to be on top of the technology to make it hack-proof, but everybody knows that car thieves are often one step ahead,” he says.

Being “one step ahead” means that the people who abuse the technology – the thieves and hackers – are often the ones who can design the best security systems. Uber certainly thinks so: the company hired Miller and Valasek shortly after they demonstrated what they could do to a car being driven miles away, using only a laptop.

Although autonomous vehicles have the potential to make our roads safer, there are still a lot of bugs to work out with the technology, and questions to answer regarding its use. The only thing we can say with any certainty is that it’s going to be a long time before the human element is completely taken out of the driving equation.

This is an extract from issue 307 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

[This article was first published in July 2017]

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard