In 1998 Stephen Hawking took me on as his PhD student “to work on a quantum theory of the Big Bang”. What started out as a doctoral project evolved over some 20 years into an intense collaboration that ended only with his passing five years ago on March 14, 2018.

The enigma at the centre of our research throughout this period was how the Big Bang could have created conditions so perfectly hospitable to life. What are we to make of this mysterious appearance of intent?

Such questions take physics far out of its comfort zone. Yet this was exactly where Hawking liked to venture. After all, the prospect – or hope – of being able to crack the riddle of cosmic design drove much of his work.

Our shared scientific quest meant that inevitably we grew close. Being around him, one could not fail to be influenced by his determination and by his epistemic optimism that we could tackle these mystifying cosmic questions.

He made us feel as if we were writing our own creation story, which, in a sense, we did.

The idea that time had a beginning in a Big Bang was championed in the early 1930s by the Belgian priest-astronomer Georges Lemaître. Albert Einstein famously rejected it, because it reminded him of Christian dogma. But eventually Hawking and Roger Penrose proved Lemaître right.

Ever since, the origin of time has been the cornerstone, but also the Achilles’ heel of Big Bang cosmology. For how exactly could time pop into existence?

Hawking’s final theory of the Big Bang provides a bold and surprising answer. It envisages the Universe as a holographic projection.

In a familiar hologram, a third dimension of space emerges from the lines and scribbles on a screen. In the cosmos-as-hologram idea, which has become the talk of the town among theoretical physicists, it is the dimension of time that can be holographically encoded.

Read more:

- Where did the Big Bang take place?

- If energy can't be created, where did it come from in the first place?

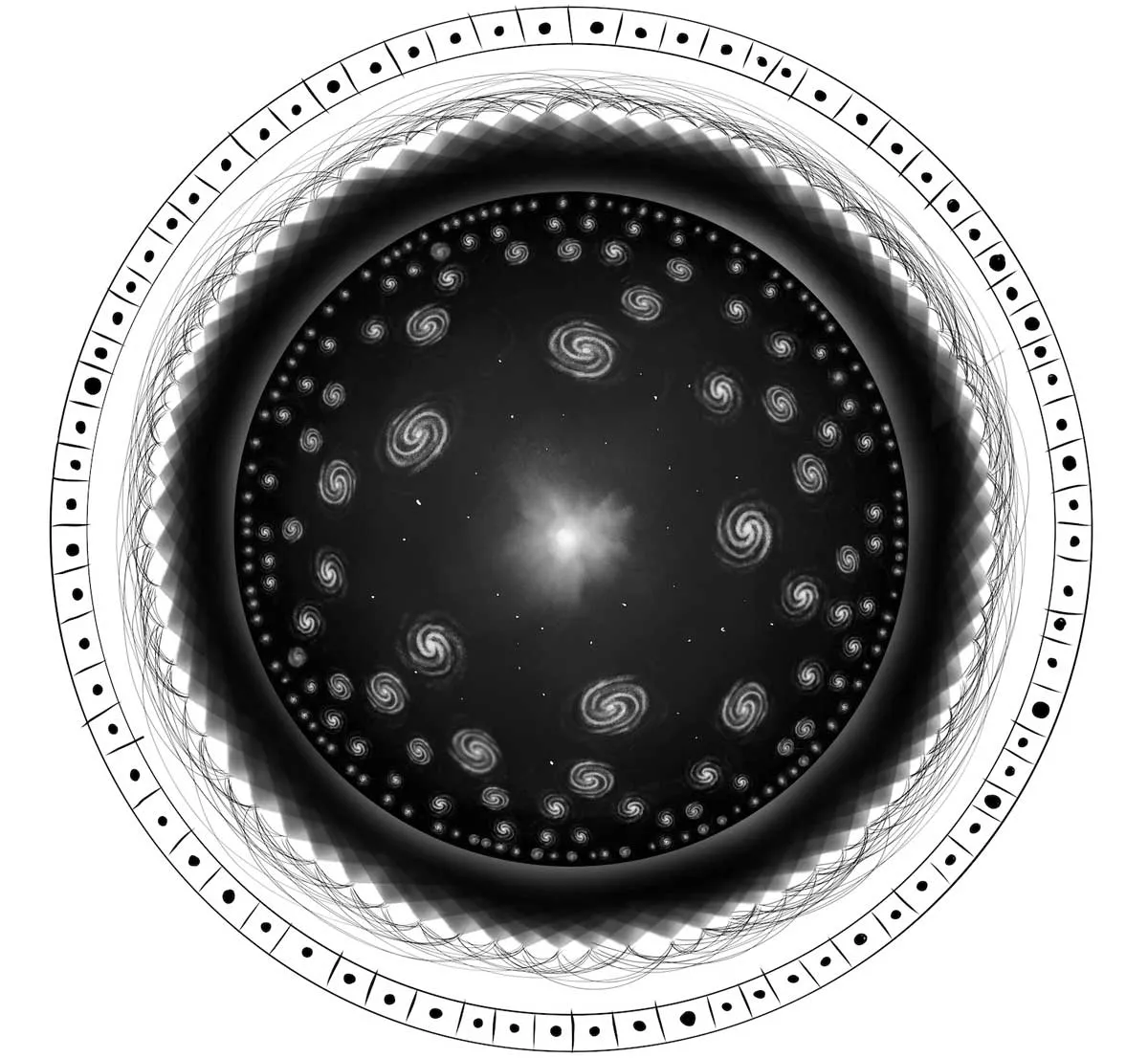

Stephen liked to visualise this idea in a disk-like image of the kind shown above. The outer circle depicts a timeless hologram consisting of countless entangled qubits.

The disk shows the evolution of an expanding Universe that projects down from this. The origin of the Universe lies at the centre of the disk and it expands outward in the radial direction.

It is as if there is a code operating on the entangled qubits that brings about the Universe and this is what we perceive as the flow of time.

Crucially, by taking a fuzzier view of the hologram, one ventures farther back in time, toward the interior of the disk. It is like zooming out. Eventually, however, one runs out of bits. This is the origin of time, according to our theory.

There can be nothing before the Big Bang, because the past that holographically emerges doesn’t extend further back.

These insights yield a new twist on the riddle of cosmic design. The early Hawking sought to describe the origin of the Universe as a quantum creation event.

In those days, Stephen strove to give a fundamentally causal explanation of the origin of the Universe: why, not how. But the discovery of holography advances a radically different view of cosmogenesis.

It says that physics itself fades away when we journey back into the Big Bang. The Big Bang emerges from holography not so much as the beginning of time but more as the beginning of laws.

What is left, then, of the age-old question of the ultimate cause of the Big Bang? It would seem to evaporate, the late Hawking held. Not the laws as such but their capacity to change and transmute has the final word.

Dr Thomas Hertog is a Belgian cosmologist at KU Leuven University and author of On The Origin Of Time: Stephen Hawking's Final Theory, is published 4 April 2023 (£20, Penguin). It is available for pre-order at Penguin and Amazon UK

Read more: