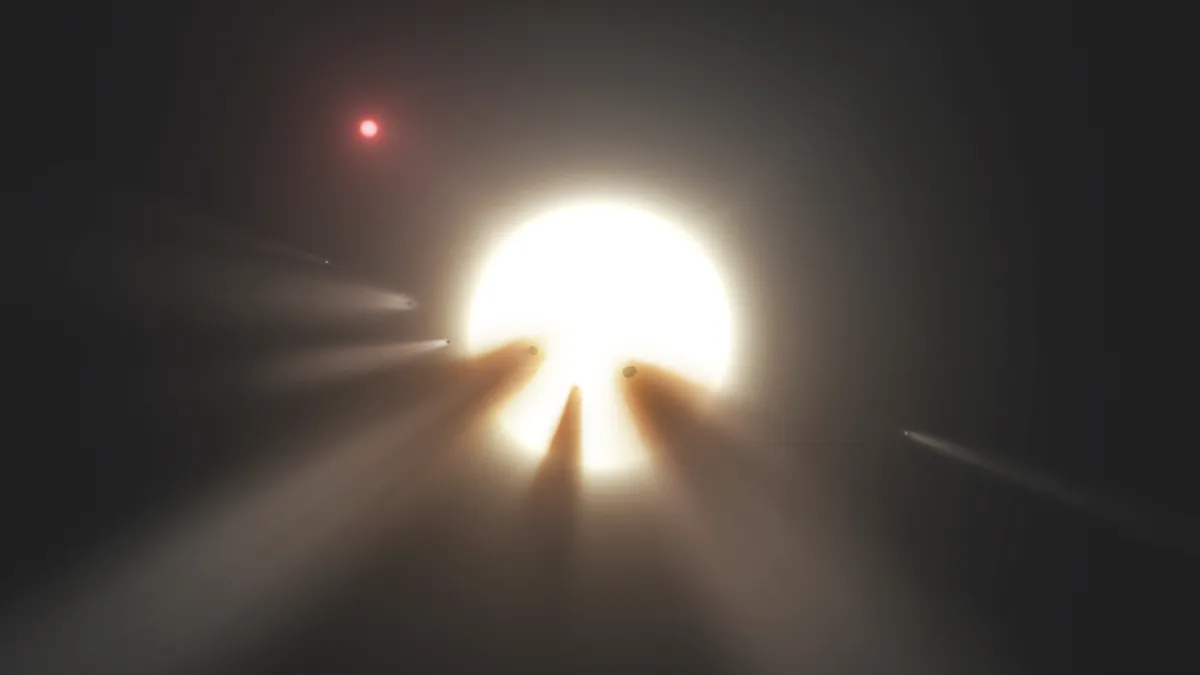

Over two decades ago, the first alien planet was detected orbiting another sun. We’ve since spotted more exoplanets, but no discovery has caused a stir quite like the star KIC 8462852 (also known as Tabby’s Star). The odd nature of this alien solar system came to light in September 2015 when astronomers were using Kepler to look for dips in the star’s brightness caused by any orbiting planets passing across its face.

Given that stars are enormous, and planets much smaller by comparison, these fluctuations are usually tiny. Even a Jupiter-sized planet passing in front of a star like the Sun only results in a 1 per cent change. And yet astronomers saw KIC 8462852’s brightness plummeting by up to 22 per cent. Nothing like it had ever been seen before.

Read more about the hunt for extraterrestrial life:

- Could ’Oumuamua really be an alien probe?

- How synthetic atmospheres could help us hunt for alien life

What rocketed the find into the news was the fact that some commentators suggested aliens might be responsible for the drop. Since it was too big to be caused by a single planet, some theorised huge megastructures created by an intelligent civilisation might be blotting out the star’s light. They imagined the dimming could be caused by vast banks of solar panels orbiting the star.

Of course there were other, far less fantastic explanations – some said it was likely that a huge swathe of comets was collectively blocking our view. Louisana State University’s Bradley Schaefer disagrees.

After poring over data, he found that the dimming has been going on for more than a century. His calculations show that nearly 650,000 giant comets would have had to pass by the planet during this time to create the recorded patterns, something he’s dubbed “completely implausible”.

The astronomers behind the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) project pointed the radio dishes of the Allen Telescope Array at the star, just in case they could hear something. “We found no indication of an extraterrestrial civilisation at the other end of the telescope,” says SETI’s Douglas Vakoch.

If KIC 8462852 turns out to be a dead end, it’ll be the latest in a line of blanks. Ever since astronomer Frank Drake undertook the first SETI experiment in 1960, we’ve detected no signals that we can definitively say are alien in origin. But that may be about to change.

A bigger, better search for alien life

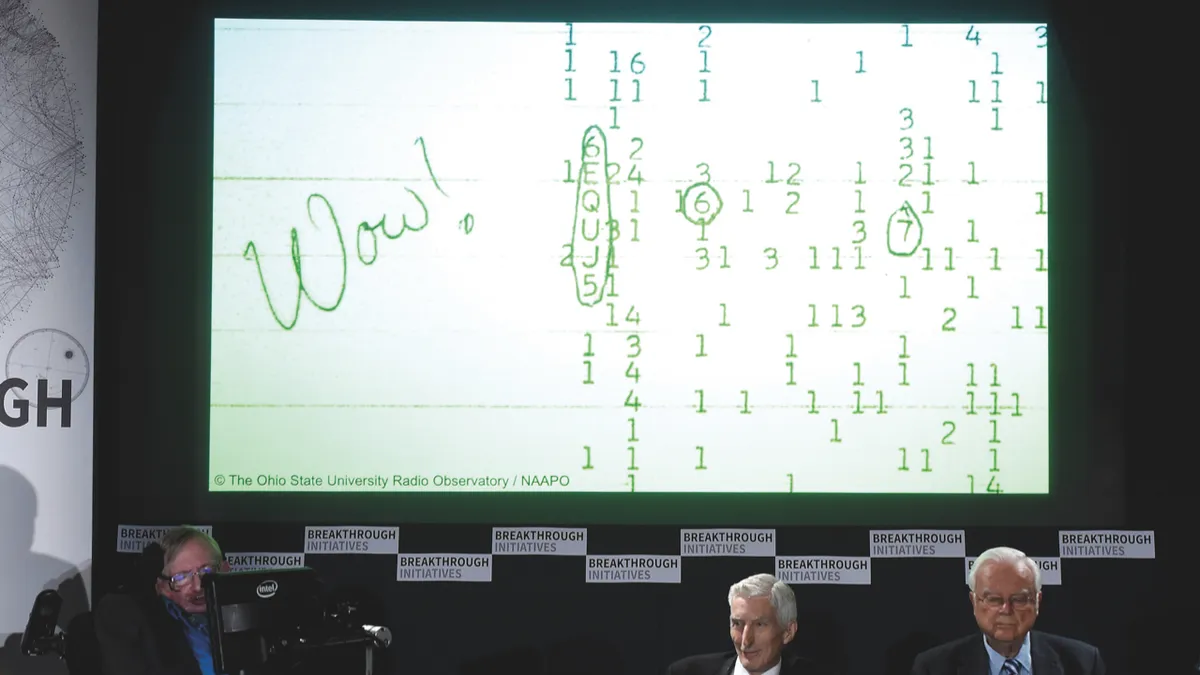

In summer 2015, the late Stephen Hawking and Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner launched Breakthrough Listen, a 10-year, $100m (£66.5m) project billed as the biggest scientific search ever undertaken for signs of intelligent life, which kicked off in February 2016.

Utilising two of the biggest radio telescopes on the planet – the 100m Green Bank Telescope in the US and the 64m Parkes Telescope in Australia – it’ll be more than 50 times as sensitive as previous searches and will cover 10 times more of the sky. It will also listen over a frequency range five times greater than before and will scan through them 100 times as fast. It will eavesdrop on the million closest stars and 100 nearest galaxies for any sniff of civilisation. The search will be sensitive enough to pick up the equivalent of aircraft radar on any of the 1,000 closest stars to Earth.

Listen to episodes of the Science Focus Podcast about communicating with aliens:

Along with Facebook’s Mark Zuckerburg, the pair also announced Project Starshot, which will send tiny rockets to search for habitable planets in Alpha Centauri, our nearest solar system.

The fact that Milner is prepared to spend such a vast sum on hunting for aliens shows just how far we’ve come. We now live in the era of exoplanet astronomy, with more than 4,000 confirmed alien worlds beyond the Galaxy. From what we’ve found so far, astronomers estimate there could be 60 billion potentially habitable planets in our Milky Way.

A famous equation formulated by Frank Drake – the Drake Equation – suggests some of them may host to intelligent life. That’s a rich seam to mine. “The search doesn’t appear as futile as in the past,” says the University of Portsmouth’s Bob Nichol, a member of the UK SETI Research Network.

As well as searching for radio signals, they will also look out for laser transmissions. But with all this excitement about detecting future alien signals, what will we do if we find something?

Confirming first contact

Should we pick up an alien signal, the first hurdle to leap is being able to show definitively that it doesn’t come from anything else.

“To start with, you’d have to put a low probability on it being alien,” says the University of St Andrews’ Duncan Forgan. Once other possibilities have been ruled out, he believes there are important checks that must be carried out. “The first is whether it’s reproducible,” he says.

If a signal is just a one-off then it’s hard to tell anything about it. This is well illustrated by the Wow! signal heard in August 1977. The intense burst of radio waves lasted for 72 seconds and was very close to the frequency that SETI researchers believe an alien civilisation might choose to communicate at. When astronomer Jerry Ehman first saw the signal on a printout from the Big Ear radio telescope in Ohio, he wrote ‘Wow!’ next to it in red ink.

But despite various efforts since, no repeat signal has ever been heard coming from that part of the sky. If a repeat is found, you can confirm it is coming from another planet by the way that planet’s motion affects the signal. “There should be a measurable shift in its spectrum due to the velocity of the planet around the star compared to us,” says Forgan.

If the discoverer(s) of the signal cannot find anything to rule out aliens, they’ll then throw it open to others teams of astronomers who will do their best to prove it isn’t from ET. “Any suspected signal would become the subject of extreme scrutiny,” says Forgan.

If extraterrestrial technology remains the most plausible explanation then, according to the official ETI Signal Detection protocol, that information should be passed to the UN Secretary General as well as a host of other international organisations. The frequency at which the signal was heard will be protected to keep that channel free from any other radio clutter, and no reply is to be sent until an international consensus on the matter has been reached.

Details of the discovery will be spread rapidly to the general population through the usual media channels, and the person or persons who discovered the signal will tell the world themselves.

It is all well and good confirming an artificial signal from an alien race elsewhere in the cosmos, but if it is a deliberate message rather some eavesdropped technological hum, how will we know what it says? After all, they are unlikely to be fluent in any Earth language. But civilisations within a few tens of light-years of Earth would have received a few decades’ worth of radio signals from Earth, so perhaps they could package up their message in a way they know we’d understand.

Alternatively, it’s been suggested that mathematics might be the language of choice for interstellar chit-chat. Initial contact could be made by beaming out a radio message encoding the list of prime numbers or the Fibonacci sequence. Once both sides know they both speak the same language – maths – you could use binary numbers to send more detailed messages such as pictures. So we’d search any potential message for mathematical structure.

Should we call back?

If we do find alien life and start up a conversation, what impact would that have on the wider population? One insight comes from a 1999 survey by The Roper Organization on behalf of the National Institute for Discovery Science (NIDS). When asked how they would cope psychologically with confirmed news of an advanced extraterrestrial civilisation, 32 per cent of respondents said they were “fully prepared to handle it” and 17 per cent said they would “rethink their place in the Universe”.

However, when asked how they thought others would respond, 25 per cent said “most people would totally freak out and panic” and 10 per cent said most others would “act irrationally and become dangerous to others”.

“Much would depend on the contents of the message,” says Forgan. Clearly, detecting the existence of advanced alien technology on a far distant planet is different from an aggressive message threatening imminent invasion. A 1997 survey found that 84 per cent of respondents believed aliens would turn out to be friendly rather than hostile.

Perhaps we can learn something about our reaction to extraterrestrial aggression from Orson Welles’ famous War Of The Worlds broadcast in 1938. The radio version of the HG Wells story was said to be so realistic that many people mistook it as factual and believed aliens were really invading. While reports of mass hysteria were overblown, the same cannot be said when a Spanish version was broadcast in Ecuador in 1949. Crazed crowds took to the streets and at least six people ended up dead.

Should the message not threaten imminent invasion, the thorniest question we’d have to confront is whether or not to send a return message. It’s a topic that currently divides astronomers.

“I was recently at a meeting of UK SETI scientists and there was a quick straw poll. The room was split exactly in half,” says Forgan. He doesn’t believe we should be sending out any kind of deliberate message into space. “I don’t think it’s a good idea to speak to someone when you have no idea who they are,” he says. “I’m not convinced we should be advertising the human race at this point in our existence.”

This is a particular issue if we’ve just eavesdropped on another civilisation without them explicitly sending us a message. They might have no idea of our existence. This hasn’t stopped astronomers before, however. The Arecibo message, for example, was beamed towards the star cluster M13 in 1974. It contained fairly intimate details of who we are and where we can be found.

Now that our search for extraterrestrial intelligence is about to move up a level thanks to Breakthrough Listen, these are questions we are going to have to grapple with properly. There may be rules for how scientists should deal with any suspected signal; what the rest of us should do and how we’re going to feel if that day ever comes is anyone’s guess. But it’s certainly an exciting time to be a citizen of the cosmos.

This extract came from issue 291 of BBC Focus magazine - for complete features subscribe here.

- This article was first published in July 2017 and has been updated for accuracy.