If you were asked to think of the ideal site for launching rockets into space, chances are your first thought would be of Cape Canaveral in Florida, where NASA’s famous moonshots began their epic journeys. Or possibly the similarly historic Russian site in Baikonur, Kazakhstan, where the launch of the world’s first artificial satellite Sputnik 1 kick-started the space race and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin blasted off to become the first human being in space. But chances are that Sutherland, a remote, rural county on the coast of northern Scotland, would be pretty far from your mind. But that is exactly the spot that the UK Space Agency (UKSA) has chosen to build the UK’s first vertical-launch spaceport.

Look beyond first impressions, however, and it turns out Northern Scotland is actually a near-perfect location to build a spaceport. And being in the north it is ideally placed for launching satellites into polar orbit – an increasingly popular practice as this allows satellites to synchronise their orbits with the Sun so that the amount of shadows in any images they take are significantly reduced. Also, the Sutherland site has the added benefit that any rockets launched there would be able to fly straight over the sea rather than over populated areas where they may potentially cause problems.

The idea of placing a spaceport in Scotland dates back at least 15 years when it was suggested that the decommissioned Dounreay nuclear power plant in neighbouring Caithness would make the ideal location for a rocket launch pad. Plans for a Scottish spaceport were revived again in 2014 when the UKSA suggested the slightly altered location of the A’Mhoine peninsula, in Sutherland. But it wasn’t until July this year that Business Secretary Greg Clark, announced that the government was stumping up £2.5 million to make the plans a reality.

If all goes to plan, Roy Kirk from Highlands and Islands Enterprise, who is leading the project, says the first launch from British soil will take place sometime in 2021. Early estimates suggest that the site will initially see somewhere between five to 10 launches a year but after that, it’s anyone’s guess. The UKSA has big plans for the site and hopes to secure a large chunk of the global space market by targeting an emerging technology: small satellites.

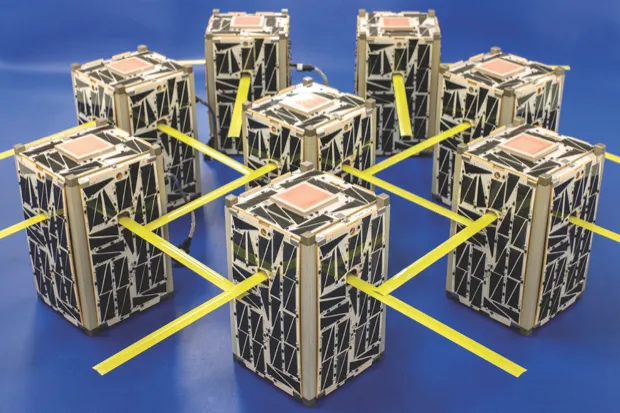

Small satellites, big plans

“We have an ambitious target,” says Claire Barcham, Commercial Space Director at the UKSA, “We want to capture 10 per cent of the global space economy by 2030. To do that the UK must become a thriving market for anyone who wants to launch a small satellite. Small satellites are transforming the economics around satellite services. They can do a lot more with a lot less.”

In certain circumstances small satellites are now capable of replacing large ones. Perhaps the key area where we will notice the small satellite revolution is in telecommunications. Traditionally communications satellites sit in a very high orbit – typically at 36,000km (22,300 miles) in a geostationary orbit – where they take 24 hours to complete a full rotation of the Earth and so appear to hover over the same spot. But, the distance for radio signals to travel up and down is large and creates a delay of about a quarter of a second that is noticeable and irritating. Small satellite constellations operating in low Earth orbit at around 500km (300 miles) in altitude will virtually eliminate this latency, improving long-distance communication for all of us.

And things are already happening. A company called OneWeb plans to use 900 small satellites to provide broadband access to remote locations. Another company, called Planet – which launched its first satellite in 2013 – intends to use a similar constellation of small satellites to provide highly accurate global imaging services. But these schemes aren’t without their obstacles. As satellites get smaller, they have ironically become more difficult to launch because the existing rockets championed by NASA, Russia and ESA are designed to hoist large satellites into orbit.

“It’s the difference between a bus and a taxi,” says Barcham. A large rocket is rather like a bus, you have to wait for it to come along and then you crowd in with everyone else. A smaller rocket is like a taxi: a bespoke, individualised trip whenever you want it.

There are a number of small launchers now being developed by companies around the world that the UK Space Agency would like to attract to Sutherland. “They have the ability to transform how technology gets into space,” says Barcham. “We’d like to make sure that the UK is in the forefront.”

Of course, the satellites are only half of the picture. We will also need a means of getting them into space. This is where UK-based private launch specialist Orbex comes in. With £30 million already secured in public and private investment, the company is well on its way to developing a rocket that’s perfect for launching small satellites.

“The company started as what the British would call a wheeze,” says Orbex CEO Chris Larmour. “Some friends and I were chatting over a beer one night and wondering how hard it was to build a Moon rocket in this day and age. We got to the point where it stopped being a wheeze and we realised it’s potentially quite doable for a small company,” he says.

The rocket the Orbex team is developing stands around 17m tall, weighs in at 15 tonnes when fully fuelled and will be capable of delivering a payload of around 200kg into low Earth orbit, and placing it in position with an accuracy of 15m. It is also remarkably eco-friendly.

“A key driver for us is being a good tenant on the site,” says Larmour. To that end, his company has gone against convention and chosen to use propane as their rocket fuel. This is exactly the same fuel that the farmers and other inhabitants use in that area to run their homes. And the fuel tank of the Orbex rocket is roughly the size of a household tank that people have in their gardens. “We are no more destructive than one farm in that area,” says Larmour.

It is not just the launches, but the buildings and roads that will be needed, and the increase in visitors and staff that the spaceport will generate that needs to be considered. Kirk and colleagues are currently engaged in an exhaustive round of public consultations with the inhabitants of the area to find the best solutions.

To space, via Scotland, America and New Zealand

As well as the start-up company Orbex, the Scottish government organisation Highlands and Islands Enterprise has also approached aerospace heavyweights Lockheed Martin only to find the American company was already thinking along similar lines. It had been investigating the possibilities of small satellite launches from the UK since the initial announcement in 2014 and had already identified a potential rocket, dubbed the Electron, being developed in New Zealand by a company called Rocket Labs.

“We are a strategic investor in Rocket Labs,” says Patrick Wood, Head of UK Space for Lockheed Martin. “The Electron launch vehicle is an incredibly good, modular design.” Electron is similar in size and capability to the Orbex launch vehicle, and has been launched twice already, performing flawlessly each time, with a further two launches scheduled before the end of the year. Once the rocket is ready for commercial use, Wood imagines starting launches at a rate of every month or two.

“We would aim to do 6-10 launches a year from Scotland. Those launches may have anything from one to six satellites on them,” says Wood. “Our goal would be to grow that number over time. This is about growing an industry and stimulating growth. We want to increase the number of apprentices and graduates who come into this industry.”

There is no doubt that satellites and their uses are changing rapidly, and that that change will bring with it the need to access space more frequently and easily. With this in mind, the UKSA is preparing to play the long game. Plans are already underway for potential other launch sites in Cornwall, Glasgow and North Wales, though these would be horizontal launch sites rather than vertical one planned for Sutherland. Vertical launch sites are traditional launch pads where the rockets travel directly up in a straight line. Horizontal launch pads are essentially beefed-up airport runways.

A launch from a horizontal pad relies on a rocket being strapped onto the fuselage or wings of a conventional aeroplane. The plane lifts off and then the rocket it’s carrying detaches, ignites and completes its flight to orbit once the plane has reached a certain altitude. In the future, it’s also possible that actual spaceplanes that are capable of ‘flying’ into orbit themselves could use these runways. One thing is certain, whether vertical or horizontal launches take precedent, the government is determined to make the UK a major player in space access.

“Our vision is to encourage companies to use the UK for launch. It will place us at the cutting edge of the space sector,” says Barcham.

T minus three years and counting…

Once the public consultations are finished, Kirk envisages lodging a planning application before the end of 2019 and then starting to build in 2020.

“We are doing lots of preparatory work. Then we will move quickly once all the consents are in place, and the community is behind it,” says Kirk. “We want to make sure the area gets the maximum benefit out of hosting the site.”

With the maiden launch from Sutherland potentially less than three years away, the countdown to the great British blast off has begun.

This is an extract from issue 328 of BBC Focus magazine.

Subscribe and get the full article delivered to your door, or download the BBC Focus app to read it on your smartphone or tablet. Find out more

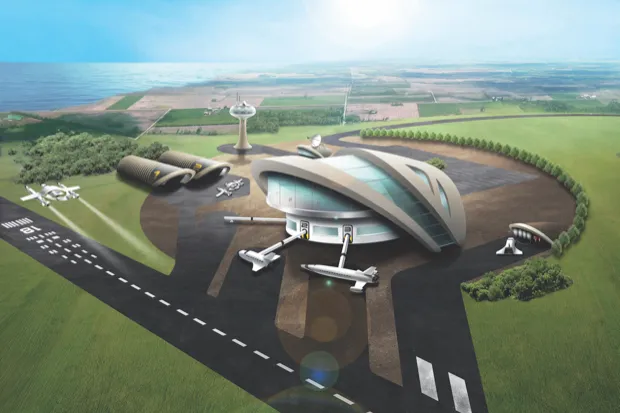

How to Build a Spaceport

A spaceport requires much more than just a launch pad. Firstly, there will have to be warehouses and laboratories where the rockets can be assembled and tested, storage tanks for the rocket fuel, a control centre to manage the launches and possibly a visitors’ centre, for spectators to watch the launch. It is also essential to have a small fire station and emergency facility in case of any mishaps. In many ways, a spaceport is similar to an airport but without the passenger terminal – yet.

Space industry statistics

- The current global space market is annually worth around £250 billion

- By 2030 the global space market is estimated to almost double its worth to around £400 billion

- Currently, the UK space industry has a turnover of £13.7 billion – around 6 per cent of the global market. It aims to grow this figure to 10 per cent by 2030

- Across the UK the space industry employs more than 38,000 people

- 74 per cent of the turnover of the current UK space industry comes from satellite applications

- £2.5 million - the amount the UK government is proposing to invest in the Sutherland spaceport

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard