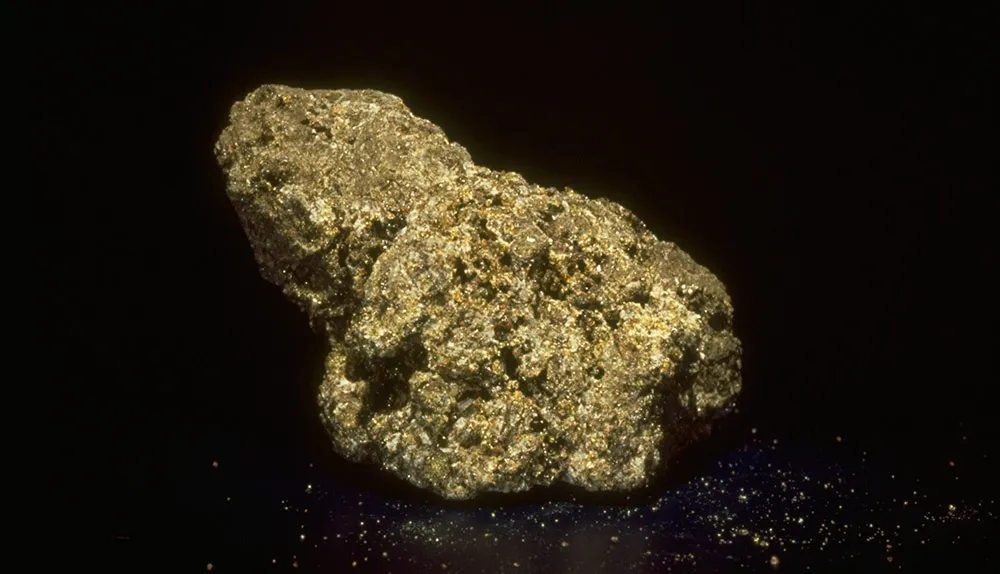

When Apollo 11 returned 22kg of lunar samples to Earth on 24 July 1969, NASA’s Lunar Sample Preliminary Examination Team wasted no time in getting the precious Moon rock into the lab. The 15-strong team was led by geochemist Stuart Ross Taylor, and included leading geologists, physicists and microbiologists. Aside from careful visual inspection, the most important analysis came from mass spectroscopy.

This involved evaporating rock samples with an arc of electricity and splitting the resulting light to look for chemical ‘fingerprints’ – light emitted at specific wavelengths by different elements. As well as the precious lunar samples, the team kept a wide variety of Earth rocks on hand for comparison.

Work on the samples began on 26 July, and in early August the team released a preliminary report that showed the rocks contained relatively high concentrations of high-melting-point elements such as titanium, yttrium and zirconium, but low amounts of volatile elements such as sodium, potassium, lead, nickel and cobalt.

It already seemed clear that some heating process had diminished the elements with melting points lower than around 1,500°C.

While this first report concluded that the balance of evidence favoured a double-planet theory, in reality it was pointing the way towards the giant impact hypothesis that would rise to prominence in the following decade.

Read more about the origins of the Moon: