Mankind’s greatest adventure, the first mission to land on the Moon, began at Cape Kennedy, Florida, at 9.32am on 16 July 1969. The ground shook as the giant Saturn V rocket slowly rose into the blue morning sky. It was only the fourth time that the booster had blasted off with a crew on board.

Saturn V flew a total of 13 times between 1967 and 1973 with a 100 per cent success record. Designed and developed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, under German rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun, it was the most powerful rocket ever built: a huge, three-stage leviathan, weighing more than 3,000 tonnes and towering 110m above the launch pad.

Inside were some 12 million working parts, which caused von Braun to say: “I find myself thinking of all those many parts – all built by the lowest bidder – and I pray that everyone has done his homework.” We look at some of the most important parts here…

Read more about the people behind the Apollo programme:

- Ladies who launch: the women behind the Apollo Program

- Small steps: How NASA prepared for the first moonwalk

- Nazis, magic and McCarthyism: the dark history of early American space exploration

- “We choose to go to the Moon”: Read JFK’s Moon speech in full

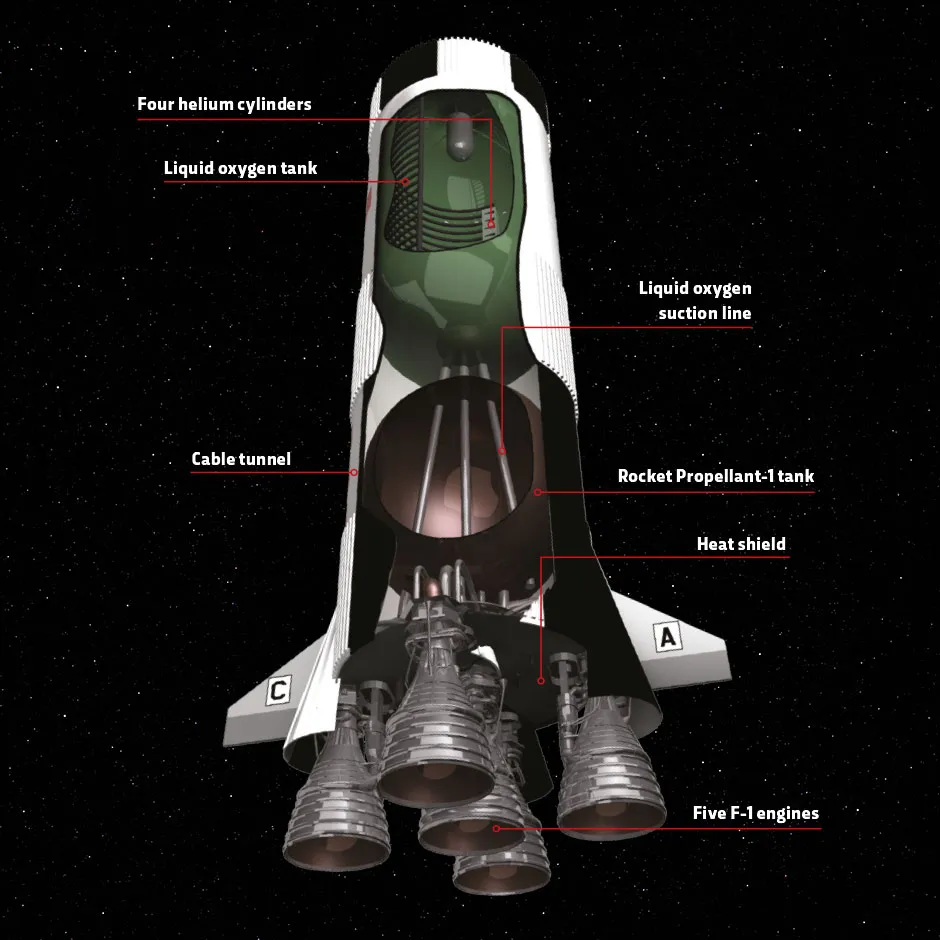

Stage One (S-IC)

Measuring 42m high and 10m wide, the Saturn V’s first stage, known as S-IC, on its own was larger than any single previous rocket. Even without its propellant, the stage weighed 139,300kg. Fully loaded with liquid oxygen and a refined kerosene, otherwise known as Rocket Propellant-1, it topped the scales at 213,566kg, almost 215 tonnes.

To lift the massive rocket off the ground, stage one’s five F-1 engines, designed by American rocket engine manufacturer Rocketdyne, had to consume about 15 tonnes of fuel each second and generate 3.4 million kilograms of thrust. They burned for two-and-a-half minutes, boosting Saturn V to an altitude of 66km and reaching a top speed of 9,840km/h.

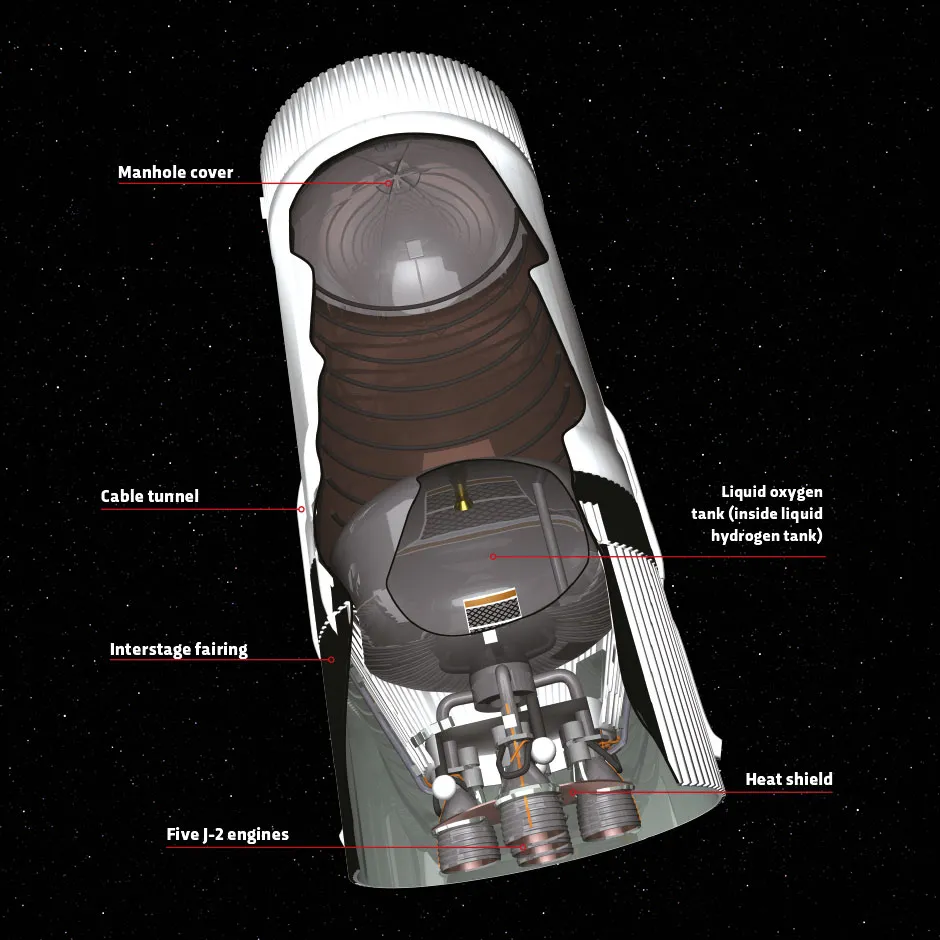

Stage Two (S-Ii)

After the F-1 engines shut down, the first stage was jettisoned, allowing the five J-2 engines of S-II, the second stage, to start their burn.

About three minutes after launch, the interstage fairing between stage one and two was also cast off, followed by the launch escape tower on the tip of stage four, as the rocket accelerated to 24,625km/h.

The J-2 engines, also developed by Rocketdyne, burned a mixture of supercooled liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. About nine minutes after lift-off, as the engines shut down, the Saturn V would have reached an altitude of 185km. By now the rocket was flying east over the mid-Atlantic and was already more than 1,600km away from the launch site.

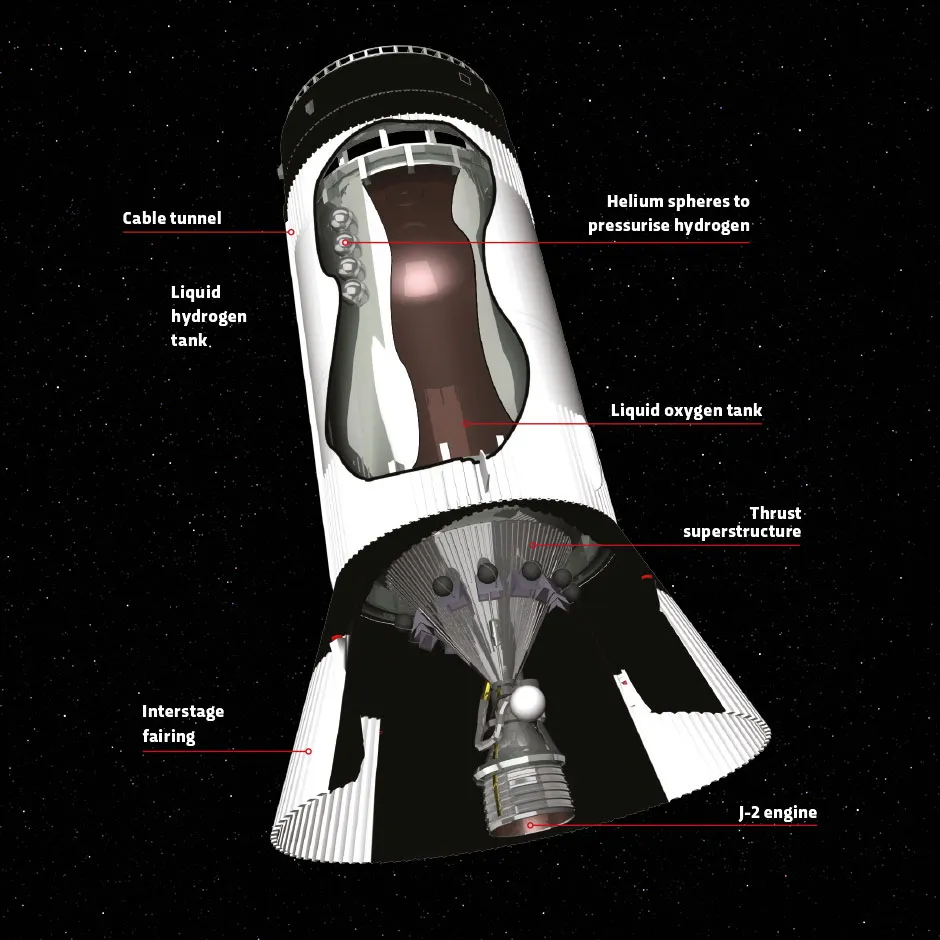

Stage Three (S-IVB)

Once the second stage had finished its burn, the third stage completed the journey to Earth orbit. This stage, S-IVB, was powered by a single, restartable J-2 engine, providing a maximum thrust of 104,325kg. The engine first fired for two and a half minutes, to increase the speed to 28,000km/h, enabling the spacecraft to enter an Earth parking orbit at an average height of 160km.

After a two-and-a-half-hour checkout period, when the spacecraft was halfway around its second orbit, the J-2 engine was fired again, for a burn that lasted five minutes and 20 seconds, to start the journey towards the Moon.

Once stage three had separated from the Apollo spacecraft (stage four), its engine fired for a third and final time to send it into orbit around the Sun.

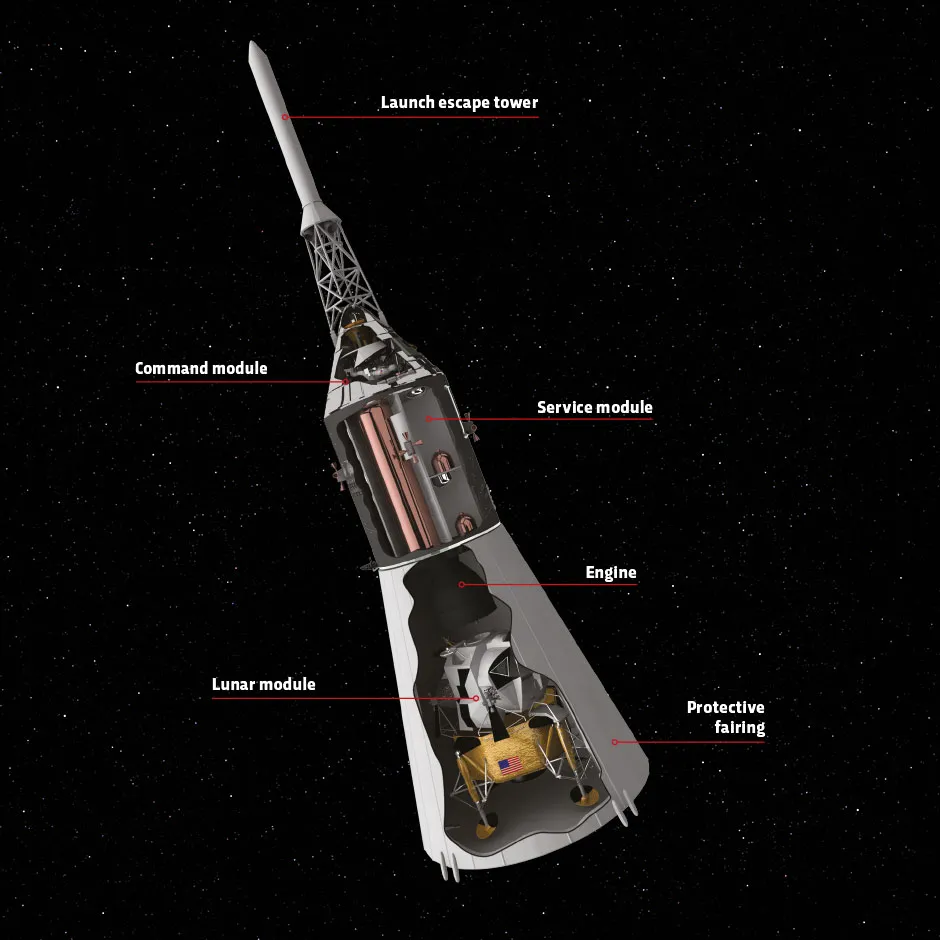

Stage Four (Apollo Spacecraft)

On top of the Saturn V was the Apollo spacecraft, which would carry the three-man crew to the Moon, land two of them on the surface and then return them all to Earth.

Stashed inside the protective fairing was the lunar module (both its descent and ascent stages), while perched on top of it were the command and service modules (CSM).

Once the flight to the Moon was underway, the fairing around the lunar module was released. The CSM then pulled away from the lunar module, rotated 180º and edged back towards it. Once the two spacecraft were docked, and the astronauts were able to access the lunar module, they were ready for a three-day trip to the Moon – the translunar coast.

Read more about the Apollo programme from around the web:

- Back on Planet Earth: what world did Neil Armstrong leave behind in 1969? via History Extra

- How the Apollo Moon landings changed the world forever via BBC Sky At Night Magazine

- Take a brief tour of the Saturn V rocket from BBC Two's James May On The Moon

- Moon Landing 50th anniversary guide: TV, film and radio shows celebrating Apollo 11 via Radio Times

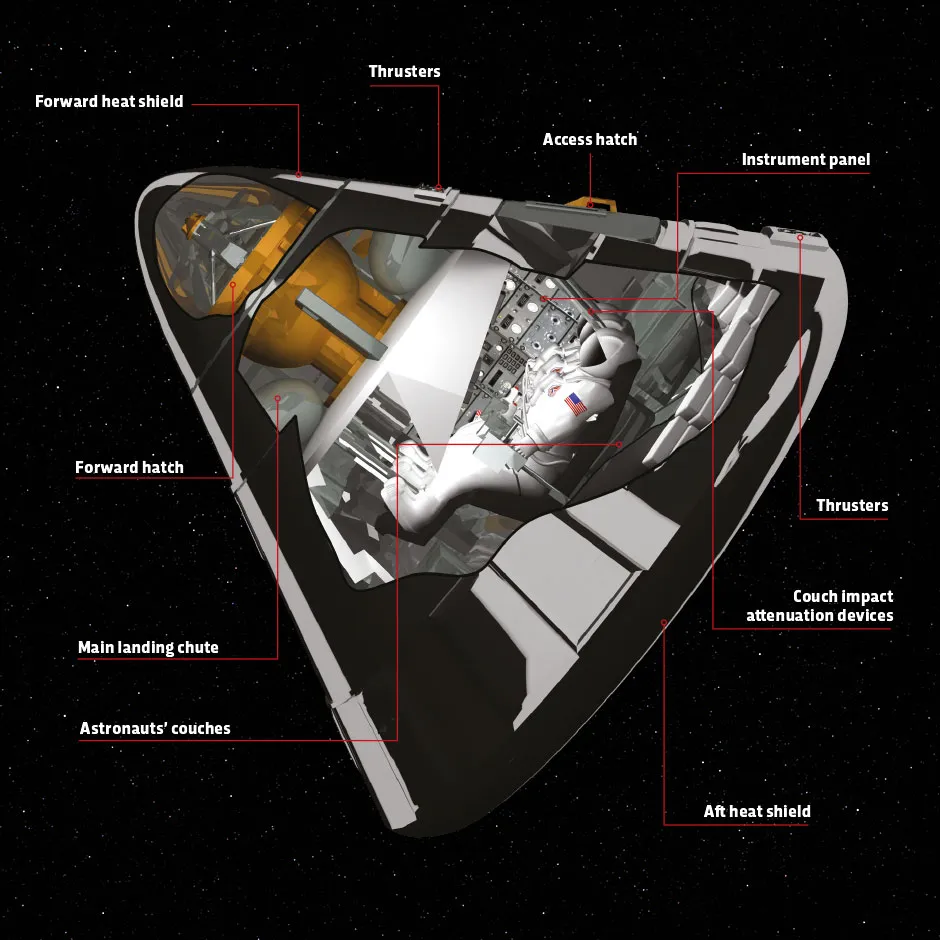

Command Module (Columbia)

The cone-shaped command module was the astronauts’ home for the eight-day mission. At its centre were three contoured couches for the astronauts that had been specially designed to reduce the effect of the g-forces generated during launch and re-entry. Arrayed around these were instrument panels, navigation gear, radios and life-support systems.

Built for NASA by North American Aviation, the command module had a launch weight of 5,570kg, was 3.5m high and had a maximum diameter of 3.9m. The main crew access hatch was at the side, with another hatch and docking probe located in the nose.

The command module came back to Earth base first, protected by a heat shield; small thrusters were fired to keep it stable during re-entry. Three parachutes deployed during the final stages of the descent to cushion the splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

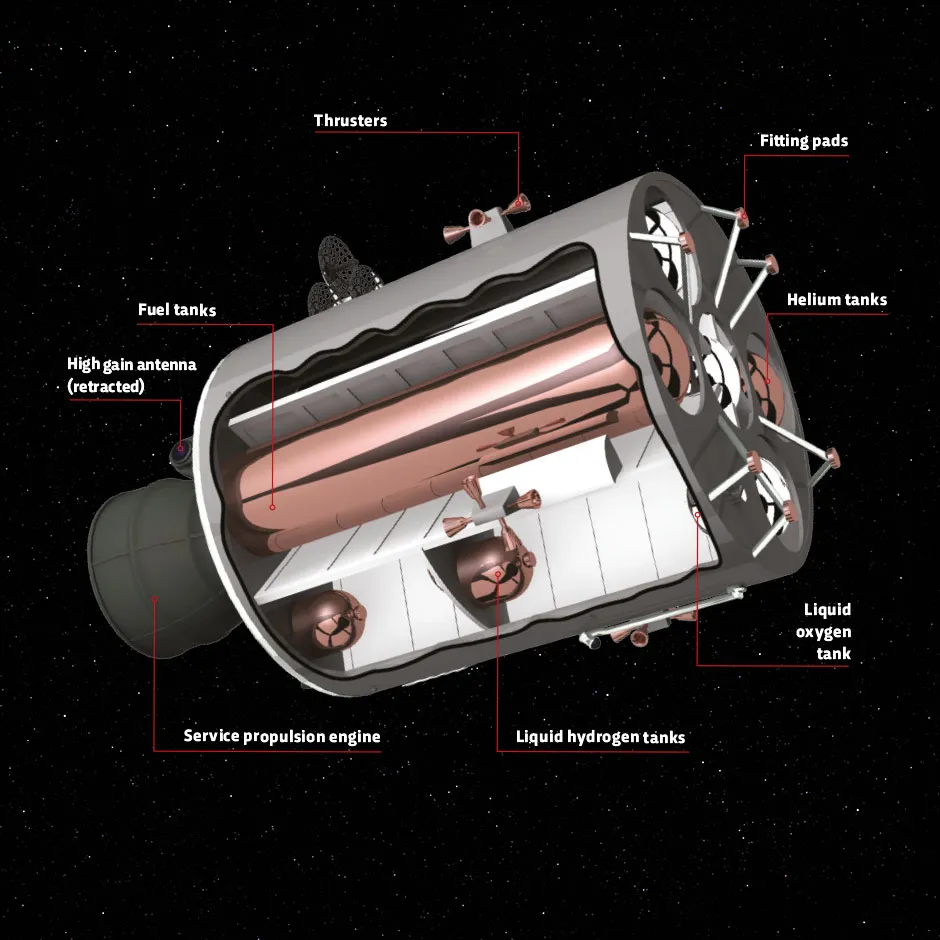

Service Module

The cylindrical service module was attached to the base of the command module right up until the spacecraft arrived back at Earth for re-entry.

Also built by North American Aviation, the service module housed most of the life-support systems needed to operate the command module on the way to and from the Moon. These included the crew’s oxygen supply and fuel cells to generate electricity, as well as tanks containing liquid hydrogen and oxygen for the fuel cells.

Small thrusters controlled the service module’s movement, while one large engine was fired to brake Apollo into lunar orbit and boost it back to Earth.

The cylinder was divided into six wedge-shaped segments around the main engine, four of which housed the propellant tanks. The propellants themselves were self-igniting.

Once back near Earth, the service module separated from the command module and burnt up as it re-entered Earth’s atmosphere on a separate trajectory.

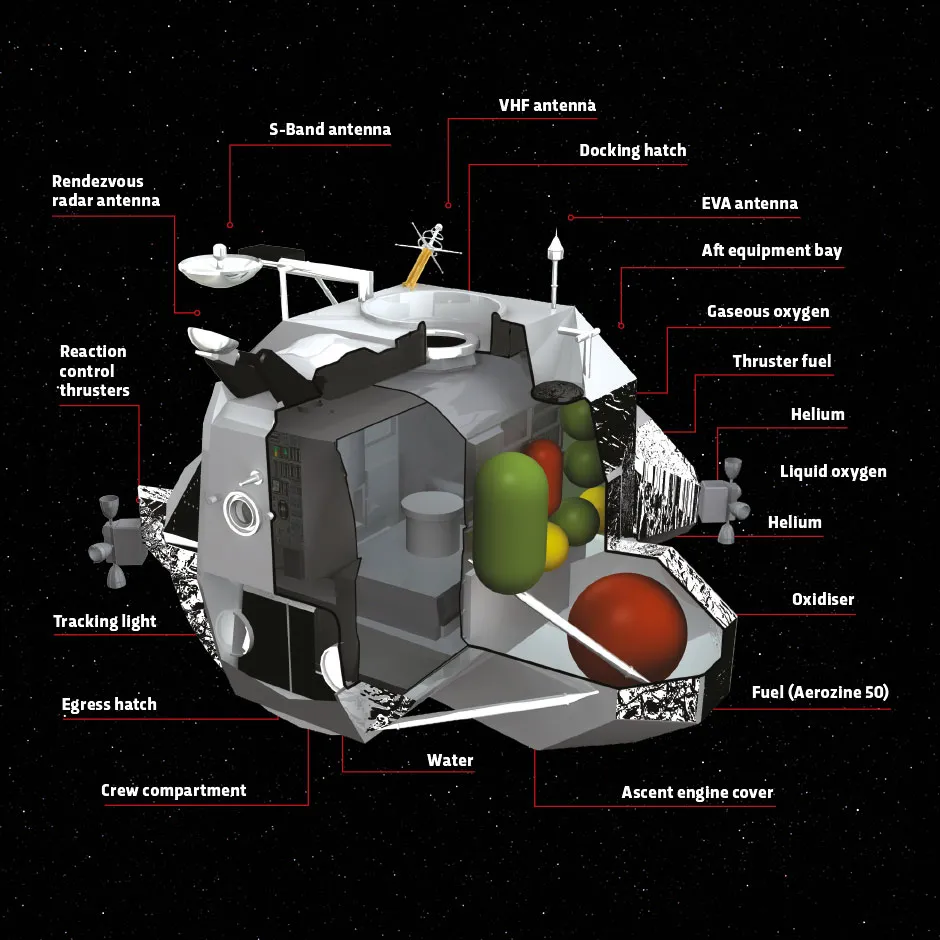

Lunar Module Ascent Stage

The lunar module, built by Grumman, stood about 7m high, measured 4.3m in diameter and would carry Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to and from the lunar surface. The crew quarters in the ascent stage included life-support systems, communications, navigation equipment and storage bays. Controls and displays for the main engine and thrusters were duplicated, allowing either crewmember to fly the craft. During the landing, Armstrong and Aldrin stood side by side, restrained by harnesses.

There were few luxuries and limited space inside: during their sleep period they had to lie on the cabin floor between boxes of rock samples and the engine cover. Once their brief stay came to an end, they fired the ascent engine to rendezvous with Michael Collins in lunar orbit aboard the command service module. The ascent stage was then jettisoned on the return journey.

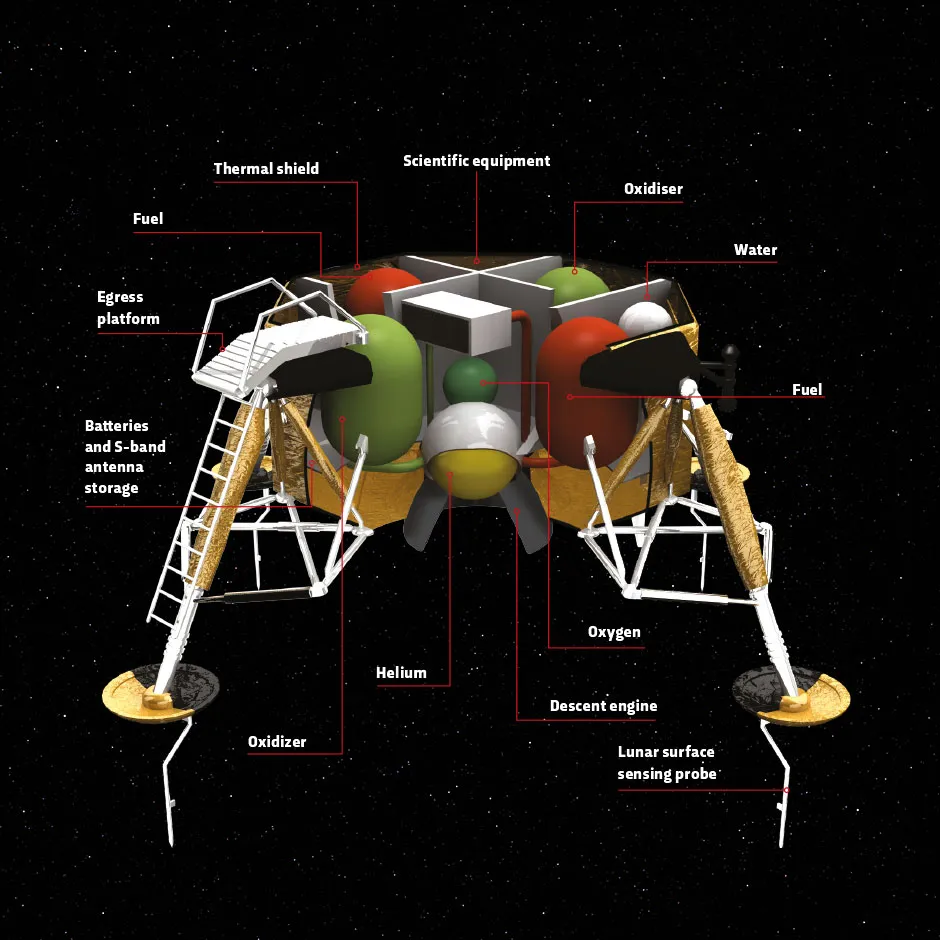

Lunar Module Descent Stage

The lunar module’s descent stage was essentially a landing platform weighing 10,334kg. At its centre was a single rocket engine that was used to slow the lunar module during its descent to the Moon’s surface and enabled it to hover while the crew searched for a landing site.

Around this were bays containing fuel tanks, water and oxygen supplies, and storage space. Extending from the four corners were legs fitted with circular footpads and shock absorbers to cushion the landing.

A 1.7m-long probe dangled beneath three of the footpads, which triggered a light in the cabin on contact with the ground. A ladder was fitted to one leg for Armstrong and Aldrin to make a careful descent to the dusty surface. The descent stage remains on the Moon to this day.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard