Not all revelations about space are about exoplanets or ancient water on Mars. We’re also discovering more about the history of space exploration – about how it happened and what motivated the early rocket pioneers. And it’s becoming clear that some of the most important engineers have been written out of the story.

The conventional roll call of rocketeers in the United States opens with Robert H. Goddard, a secretive Clark University physicist who experimented with liquid propulsion. For Goddard, the goal of a rocket was to reach ‘extreme altitudes’ though he never quite managed this himself.

Next up is Wernher von Braun, the architect of the Nazi V-2 who subsequently designed the Saturn V launch vehicle that took America to the Moon.

But in between these two is another engineer, Frank J. Malina, who has been largely forgotten. Why?

Space is political

As ever in the history of science, the question of who gets remembered is not just about technical or conceptual contributions. It’s also about whether the scientific story fits with the values and ideals of those with the power to tell it.

Consider Frank Malina, an earnest graduate student at Caltech, Pasadena. Unlike Goddard, his liquid propelled WAC Corporal was the first American rocket to reach extreme altitudes. It soared to 73km compared to Goddard’s 2.5km.

Frank Malina, however, is hardly known – despite his founding NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. His anti-fascist activism in the late 1930s brought him to the attention of the security services in the McCarthy era.

In the midst of the Cold War Space Race, few wanted to celebrate an anti-racist campaigner. After all, that kind of thing looked dangerously communist. The complication? Newly declassified FBI files show that Frank Malina really was a member of the Communist Party.

Wernher von Braun, by contrast, might have been an anti-Semitic SS member but he was fervently anti-communist. His Nazi political baggage didn’t seem to weigh him down: Walt Disney beamed von Braun into living rooms as FBI agents sat in a car outside Malina’s house. Frank Malina finally left the United States, upset that his rocket was destined to be a weapon of war rather than a vehicle for science.

Nazis helped America reach the Moon

It isn’t exactly news that the US military transferred von Braun and another 1,600 engineers from Germany to the United States after the collapse of the Third Reich. And, yes, this team did indeed make formative contributions to the Apollo programme.

These included Arthur Rudolph, the project director for Saturn V engines (“I read Mein Kampf and agreed with a lot of things in it”, Rudolph told a journalist in 1985, “Hitler's first six years, until the war started, were really marvelous”).

Read more about great scientists from history:

- Lise Meitner: the nuclear pioneer who escaped the Nazis

- Wally Funk: a story of sexism in the race for space

But the V-2 team, many of them unrepentant Nazis, have tended to eclipse the engineering achievements of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Many important rocket developments – successful electronic guidance systems, solid state propellants, hypergolic propellants that combust on contact – were home-grown in the United States rather than derived from the V-2.

The invention of solid rocket propellants featured magic as well as science

One of the key inventors of solid rocket propellants was Jack Parsons, a self-taught chemist, who is now as well known for his occult activities as for his contribution to practical rocketry. A devotee of English ceremonial magician Aleister Crowley, Parsons reputedly recited Crowley’s Hymn to Pan while conducting static tests of his Jet Assisted Take-off (JATO) rocket devices in 1941.

Parsons’ collaborator Frank Malina attributed his friend’s ‘poetic spirits’ as an influence on Parsons’ unconventional scientific thinking. In many ways, however, these unusual beliefs hark back to the Early Modern origins of science – an era when figures like Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton understood science and magic as allied, rather than oppositional, enquiries into the natural world.

Malina was always keen to credit Parsons’ rocketry contributions, not knowing that Parsons was, in fact, informing on Malina to the FBI. Variants of Parsons’s ‘castable’ solid propellants are now used in everything from ejector seats to Trident nuclear missiles.

American McCarthyism propelled the Chinese space programme

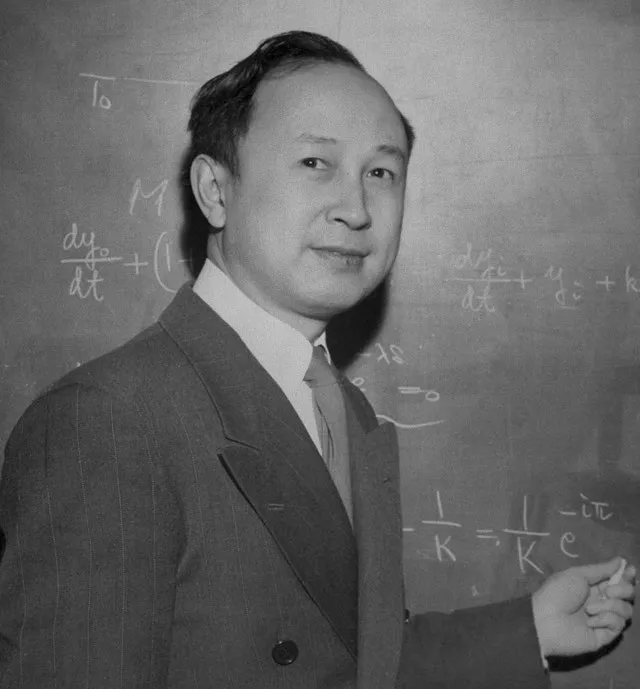

Among Frank Malina’s closest colleagues was the Chinese rocketeer Hsue-Shen Tsien (now Qian Xuesen) who, together with Malina and their Caltech doctoral supervisor Theodore von Kármán, pioneered some of the theoretical work on rocket propulsion.

Tsien, too, joined the Communist Party in 1938 in a bid to combat the rise of fascism abroad and racial segregation at home in California. It was a time when the rise of Nazi Germany made such political activism seem urgent.

But by the late 1940s, this kind of conviction was understood very differently. The idea of ‘reds’ working with classified military information prompted concerns about espionage.

JPL Director Louis G. Dunn was particularly suspicious of colleagues whom he deemed ‘definite leftists’. In January 1949, Dunn told the FBI that he thought some engineers in JPL may be spies, singling out Jewish and Chinese engineers – including H.S. Tsien.

There’s no evidence that Tsien was involved in espionage, but his case presented a problem for the US Government: should they deport him to demonstrate their domestic toughness on communism? Or keep him in the California, lest his expertise be put to work for their communist rival China?

Listen to Science Focus Podcast episodes about the Moon landing:

- Why is the Moon landing still relevant 50 years on? – Kevin Fong

- The mindset behind the Moon landing – Richard Wiseman

The US chose deportation, handing over the expertise for China to start its own rocket programme. Premier Zhou Enlai was delighted: China went from being a country capable of producing bicycles and a simple car to being the third country to independently send humans into orbit.

It’s no coincidence that, earlier this year, when China successfully landed a rover on the far side of the moon, it chose to target the von Kármán crater – a less than subtle nod to how American anti-communism propelled China into space.

What counts as ‘space’ and the limits of Earth have changed

Frank Malina’s WAC Corporal may have soared to 73km in 1945, but it’s not considered the first rocket into space. That honour belongs to the German V-2 which crossed the 100km threshold, the modern definition of space, in 1944.

There’s a complication: the modern definition of space – the Kármán line – was only settled in 1963, and even this is to some degree a ‘folk theorem’. It’s an idea that emerged at a conference when von Kármán argued that, at around this height, the atmosphere becomes too thin to support aeronautical flight.

Even though the Kármán line has become the standard definition of space, a recent proposal by Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell suggests bringing it down to 80km. The logic is that this is the lowest altitude at which a satellite can still orbit the Earth.

None of this changes the primacy of the V-2. But when Malina’s WAC Corporal was ‘mated’ on to a V-2 to create the two-stage Bumper Wac Corporal in 1949, it reached a record altitude of nearly 400km – the highest altitude then achieved.

Some observers at the time considered that this journey, rather than the 1944 V-2, was the first time a rocket had properly escaped from Earth, reaching into what was then called ‘extra-terrestrial space’. They weren’t wrong, exactly. It’s just that such flights have been part of what has helped us to determine the indistinct boundaries of Earth and space.

Escape from Earth: A Secret History of the Space Rocket by Fraser MacDonald is available now (£20, Profile Books)