Although the first months of 2022 have provided us with little in the way of observable astronomical events in the night sky, the Lyrid meteor shower marks the first major meteor shower of 2022and will hit its peak this week.

So, what is the best way of making sure you see the Lyrid meteor shower? What causes it in the first place? And when exactly should you look for it? Answers to all this, and more, are below.

Plus, if you’re looking for more stargazing tips, be sure to check out our astronomy for beginners guide and our UK full Moon calendar.

When can you see the Lyrid meteor shower 2022 in the UK?

The Lyrid meteor shower began on 14 April 2022 and will continue through to around 30 April.

The Lyrid meteor shower will peak on 22-23 April, and the best date to see the Lyrids will be between 22 April and 26 April 2022.

As with any meteor shower, it helps if the Moon is not bright. By the time the Lyrids reach their peak on the night of 22/23 April, the Moon will be in the third quarter but crucially, it doesn't rise until 3:26am. Therefore, on this occasion, the Moon will not impede much on viewing conditions. Before moonrise, look up at an angle of around 60° and you should be able to catch a glimpse of a meteor or two.

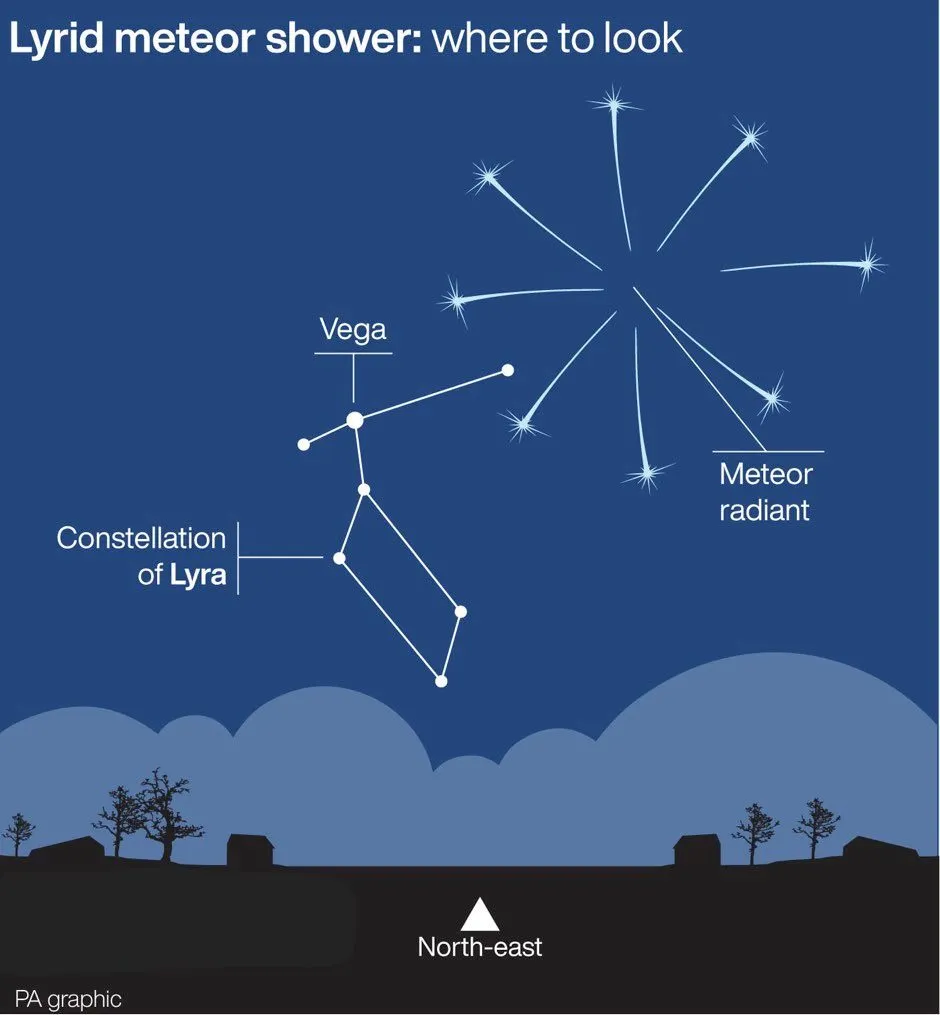

Although the Lyrids will appear to originate from the constellation of Lyra, it’s best to look towards whichever part of the sky is darkest for where you live.

What is a meteor shower and what causes it?

A meteor shower is usually caused as the Earth passes through debris left over from a passing comet. Most of this debris is small, no bigger than a grain of sand, but when this debris enters our atmosphere, it disintegrates leaving a display of bright trails in the sky.

If the debris is larger and survives the journey through the atmosphere to the Earth’s surface, these are called meteorites. You might remember the now-famous Winchcombe meteorite, a 4.6 billion-year-old meteorite that landed on the driveway of a house in Gloucestershire.

Why do Lyrids appear to originate from a single point in the sky?

It's all down to perspective. The meteor shower actually hits our atmosphere from the same direction, as all the bits of debris are on parallel paths. And because Earth moves relative to the position of the orbit of this debris, the radiant appears to shift slightly over subsequent nights. The size of the radiant can also be a good indicator of the age of the meteor stream. For example, a small radiant is suggestive of a young, hardly dispersed stream.

If you can, look towards Vega, the brightest star in the constellation Lyra.

How many meteors will you be able to see?

At its peak on the 22-23 April, the Lyrid meteor shower has a zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) of 18 meteors per hour. This refers to the number of meteors (per hour) that can be seen under a clear sky when the radiant (the point from which meteors appear to originate) is directly overhead.

In reality, we are likely to see less than this - typically around 10 to 20 per hour, although as many as 100 per hour have been seen.

Where do the Lyrids come from?

The Lyrids originate from debris leftover from the Comet Thatcher (or C/1861 G1 Thatcher to use the official designation). This is a long-period comet that takes approximately 415.5 years to complete one orbit around the Sun. It was last in our Solar System in 1861 and won’t be back until the year 2276.

The Lyrids are also one of the oldest known meteor showers, and the first recorded sighting goes way back to 687 BC – that’s over 2,700 years ago!

Viewing tips

If you can, find an area away from light pollution. Night temperatures on the 22/23 April are expected to be fairly mild – around 11°C here in Bristol – but be sure to check your local weather forecast. It’s worth wrapping up warm, as you’re probably not going to be moving around much.

Lie back in a reclining chair, hammock, or on a blanket, and let your eyes adjust to the darkness for around 10 to 20 minutes.

After a while, and with a little patience, you’ll find you become more accustomed to seeing the Lyrid trails, as they streak across the sky, each observable for several seconds. Try not to look at other bright sources of light (such as your phone) during this time, or if you do, use a red filter.

Read more about space rocks: