First impressions count and few are better than the boot print Neil Armstrong made when he stepped on to lunar surface in 1969. His words – “one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind” – also had an impact. Although it’s unlikely that such gendered language would be used today, at the time they reflected a different era and a simple truth: it was a man’s world.

Fifty years later, as humanity prepares to return to the Moon, people might be forgiven for thinking that not much has changed. A few months ago, after much advance publicity from NASA, a man took part in what was intended to be the first scheduled all-women spacewalk. The decision to replace Anne McClain by her male colleague, however, was based on practicalities and made by McClain herself.

Read more about women in science:

- Why aren't there more women in science?

- 10 amazing women in science history you really should know about

- Hidden Figures: the incredible real history behind the film [via History Extra]

Like many astronauts on board the International Space Station (ISS), McClain’s height had changed. Because the fluid between vertebrae expands in microgravity, she had grown by approximately 5cm. A snug medium-sized spacesuit was now the best fit yet only one of two medium suits was primed and ready.

Since every minute of an astronaut’s time is accounted for, McClain’s spacewalk was rescheduled. But it was an embarrassing own goal. Instead of celebrating another ‘first’ for women in space, it brought renewed attention on how the default size – even in space – is usually male and large.

Vital work, unrecognised workers

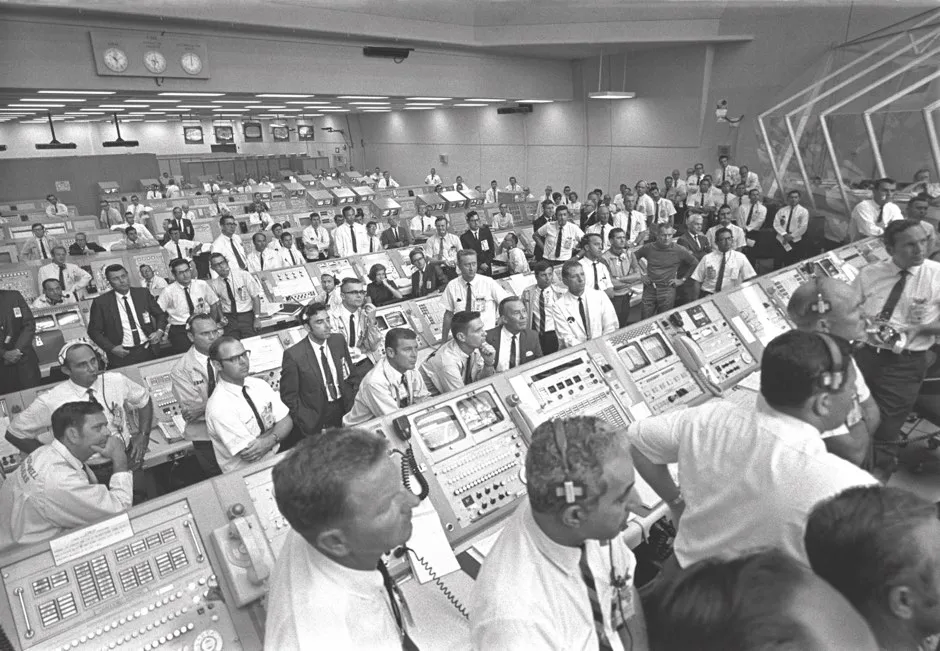

Back in 1969 such assumptions were understandable. Despite their presence throughout the Apollo programme, women in the space industry were not – as is often the case today – celebrated. It’s only recently, for instance, that people learnt the identity of the sole woman pictured inside the Launch Control Center at Cape Kennedy for the Apollo 11 mission. It was JoAnn Morgan.

Morgan was an instrumentation controller and engineer. Before that, she worked to protect guidance systems from electronic interference – Morgan had to thwart the efforts of Russians aboard nearby trawlers trying to meddle with the launches of Apollo 8, 9 and 10. Not everyone appreciated her position. Occasionally, during her duties, she received obscene calls on her console phone. Since there were no women’s toilets, she had to either wait for a security guard to empty the men’s room or walk to a different building.

The latter scenario will be familiar to readers of Margot Lee Shetterly’s book, Hidden Figures, or the film of the same name. It focuses on the group of women ‘computers’ at Langley Research Center in Virginia who, in 1962, played a role in sending astronaut John Glenn into space.

Unlike Morgan, who is white, the women featured were African American and, due to the colour of their skin, experienced far more than sexism. Apart from segregated restrooms in different buildings, they were initially expected to eat at a separate table for ‘colored computers’.

The contributions of engineer Dorothy Vaughan and mathematicians Mary Jackson and Katherine Johnson, whose orbital calculations were also used in the earlier Apollo missions and helped get Armstrong and his crew to the Moon, are now more widely known.

As is Margaret Hamilton, lead computer programmer of a team at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, whose software was vital for the Moon landings and was later adapted for Skylab and the Space Shuttle. In 2017 Hamilton was part of Lego’s best-selling ‘Women of NASA’ set, which recreated a photograph of her standing alongside stacked volumes of Apollo navigational software.

In fact, women in a range of roles helped put the first people on the Moon. Electrical engineer Judith Love Cohen, for instance, helped design the Abort Guidance System computer on Apollo 11’s lunar module and its software. Cohen graduated as an engineer at the University of Southern California (USC) and continued studying there for further qualifications while working.

“She always said that she never saw another woman engineering student during her time there from 1952 to 1962,” recalls Neil Siegel, IBM Professor of Engineering Management at the USC School of Engineering and Cohen’s son.

Cohen was only the eighth woman to graduate from USC as an engineer. “She had a full-time day job as an engineering associate and then as an engineer during these years, in addition to having the first three of her four children, and so mostly attended night classes,” says Siegel. “So perhaps it’s not surprising that she never saw another woman engineering student. She also told me that the engineering buildings did not have women’s bathrooms.”

Safe return

Like many of the pioneering women in the space industry, Cohen encountered resistance. Early on in her career, reviewing missile systems, a male colleague repeatedly told her that she was ‘a girl scout trying to earn a merit badge at their expense.’

Thankfully she didn’t give up since Cohen’s work helped save the crew of Apollo 13. When its service module was damaged by an explosion on its way to the Moon, there was a near total failure of power in the command module.

“The crew had to move to the lunar module for the rest of the mission, to stay warm,” says Siegel. “But the lunar module was only designed to hold two people, not three, and wasn’t designed to be powered on for several days – the time it would take to effect the return to Earth.”

The computer for in-flight navigation in the command module had to be turned off but fortunately there was a computer inside the lunar module for its own navigation if, for any reason, the landing had to be stopped: Cohen’s Abort Guidance System.

“This Abort Guidance System computer was re-purposed to perform the guidance needed to navigate the command module back to Earth,” explains Siegel. “She also participated on the orbitology team that designed the return-to-Earth orbit, and convinced NASA – against their initial desires – to incorporate this orbit design into the design for the mission,” he adds. “Without the return-to-Earth orbit design, the Apollo 13 astronauts could not have gotten home.”

Dressed for success

Women’s work during the Apollo programme also included more traditional jobs for the time. Dee O’Hara, for instance, was the astronaut nurse who began with the Mercury Seven, America’s first astronauts. There were also the women who transferred their sewing talents to a more unusual application.

The International Latex Corporation, as ILC Dover was initially known, originally made girdles, using a variety of durable and flexible materials, and employed a number of women. In 1962 the company won a contract to make spacesuits for NASA. Its spacesuits were worn by the Apollo astronauts and today’s versions are on board the ISS.

Read more about the Apollo Moon landing:

- The Space Race: how Cold War tensions put a rocket under the quest for the Moon

- 50 beautiful photos of the Moon landing missions from the Project Apollo Archives

- “We choose to go to the moon”: Read JFK’s Moon speech in full

“The women seamstresses were a prime factor in making the Apollo spacesuits a success,” says William Ayrey, a spacesuit test engineer and company historian for ILC Dover.

“They had to work closely with the engineers to carry out their ideas of how a properly assembled spacesuit could hold up to the challenges of working on the Moon,” says Ayrey. “Often the engineers might have had an idea of how sewn parts could be put together but the seamstresses were the ones who had to make it work so they would have to show the engineers how it should be done.”

According to Ayrey, working on spacesuits was “much more challenging than sewing any other typical garment or drapes.”

The spacesuit was “a life-sustaining garment that could take the life of an astronaut if it failed. Some seams included what was called a blind-stitch,” he says, “where the seamstress could not see what was being sewn. She had to feel underneath as it was being assembled.”

The lives of the Apollo astronauts depended on the seamstresses’ skills and their work was appreciated. “The women did get proper credit and were often selected to witness the Apollo launches as a reward,” says Ayrey. “The astronauts liked to visit with the seamstresses when they came to ILC Dover for their fit-checks in their space suits and recognise the women’s work.”

Even modern NASA spacesuits are more likely than not to have been put together by women since, according to Ayrey, there is currently only one man on the team at ILC Dover. “The spacesuits are still very labour intensive and they remain a life-critical item.”

The Mercury 13

Today at NASA there are women doing almost every conceivable job – there are female mission controllers, scientists, engineers, managers, flight surgeons and, of course, there are also women in the more attention-grabbing roles such as astronaut. Some women, like Dr Ellen Ochoa, have also managed to combine a number of roles; Ochoa’s been an astronaut, an engineer and from 2013 to 2018 was the director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

Despite Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova upstaging the Americans in 1963 by becoming the first woman in space, and despite the number of women employed behind the scenes during the Apollo programme, not one American woman went to the Moon. This was not only a missed opportunity and but also a missed propaganda coup because the US had women ready to become astronauts years earlier.

Before Apollo, during Project Mercury when America chose its first seven (all male) astronauts, the same medical director who devised the selection tests recruited female pilots on a privately funded ‘Woman in Space’ programme. Dr Randolph Lovelace wanted to see if women had the right stuff too.

Lovelace’s test case was aviator Jerrie Cobb in 1960. She performed so well that Lovelace extended the tests to other female pilots. The women who succeeded between 1960-1961 are now collectively known as the Mercury 13. The youngest was Wally Funk. The oldest was Janey Hart, aged 40 with eight children.

Hart, together with Cobb, tried but failed to get NASA to allow women astronauts at a congressional hearing in 1962. Afterwards Hart received hate mail asking her to stay at home with her children. NASA wouldn’t admit women into its astronaut corps until 1978 but these trailblazers helped make it possible by showing that they could pass the same tests as the men.

Funk refers to that time as being a “good-old-boy network” and remains determined, at the age of 80, to get into space, so much so that she’s purchased a Virgin Galactic ticket. Unlike Cobb, who died recently aged 88, Funk may actually make it.

Three of the Mercury Seven – Alan Shepard, Deke Slayton and Wally Schirra – all went on to become Apollo astronauts. So if the Mercury 13 had been admitted to NASA’s ranks back in the early 1960s, one of those women – possibly even Funk herself – could also have been part of humanity’s excursions to the Moon.

The many women involved during the Apollo missions, these ladies who launched, are inspirational. But just imagine how society would have viewed the roles of the sexes today if just one of those Moon walkers – who continue to receive worldwide admiration – had been a woman.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard