Fancy yourself as a bit of an explorer? Then best pay very close attention to Dr Kathy Sullivan.

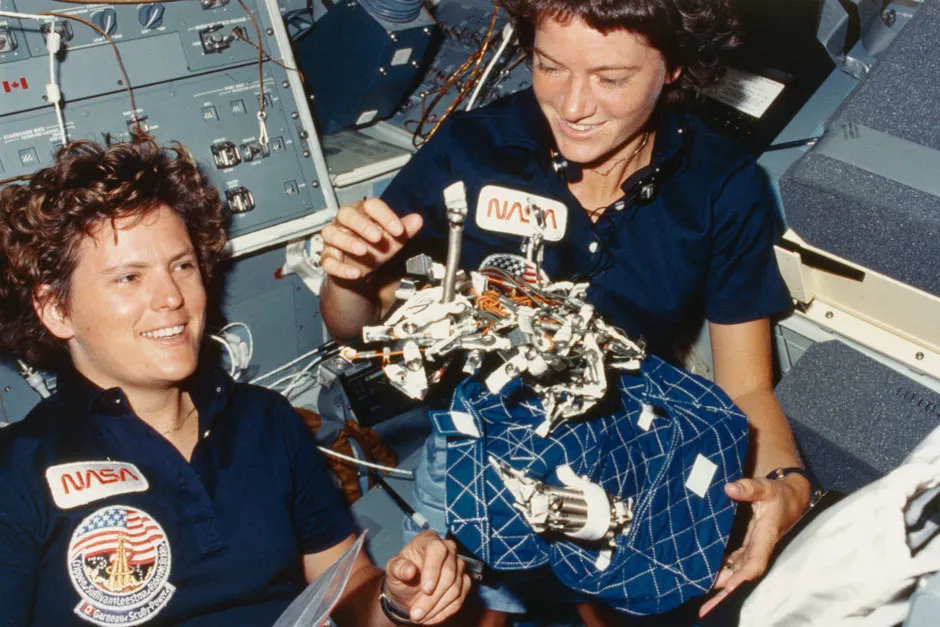

Not only is she the first American woman to walk in space, but she’s also *deep breath* one of the astronauts who deployed the Hubble Space Telescope, the first woman to dive to the deepest point in Earth’s oceans (the Mariana Trench), a retired captain of the US Navy, a veteran geologist and a former US Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In short, with a CV like that, it’s always worth listening when Sullivan speaks. That’s why we sat down with her ahead of the launch of Lego’s new Discovery shuttle, the real one of which Sullivan flew in April 1990, Hubble in tow.

Sharing her wealth of wisdom and experience, Sullivan opened up about the future of human exploration, how diversity is critical to spaceflight’s success, and why having the first person on Mars be a woman could reap immeasurable rewards.

(If you want to hear more from Sullivan, she previously discussed her historic spacewalk on our podcast).

On 12 April, NASA is marking 40 years since the launch of the first Space Shuttle (Columbia, 1981). Why do you think the shuttle programme captured people’s imaginations?

I think partly it was such a unique design – it was a mind-bending notion to launch like a rocket and land like an aeroplane. It bridged the familiar and exotic for people.

But, importantly, the Space Shuttle era also saw a lot of different people in space. You saw younger people, you saw women, you saw people of colour in space.

Recently, the European Space Agency opened applications for astronauts, encouraging women in particular to apply. Why is diversity so important in space exploration?

Two reasons. Firstly, there’s the practical side. A wider range of prior experiences and frames of reference really matters when you’re trying to do something creative. Common groups of people are shaped by common sets of experiences. That gives you blinkers.

But mix more people in with different perspectives, different backgrounds and the amount of lateral thinking and creativity just soars. Absolutely soars.

Secondly, if you really mean you come in peace for all mankind, then you ought to be bringing all mankind with you.

Read more about astronauts:

- Weightlessness could make astronauts worse at recognising emotions in others

- This is your brain on space: how gravity influences your mental abilities

- Tim Peake: finding even a single cell on Mars would be “hugely significant”

What would it mean if the first person on Mars was a woman?

I think to countless young girls it would provide a dream, a point on the horizon and a dose of confidence – they could see somebody else do it and know it’s possible. And it could inspire parents – including fathers – to want to make sure their daughter has large-scale possibilities open to her.

In practical terms, it would depend on the nature of that mission whether it was actually a woman or not. I don't think anyone does physics fundamentally different. If you’re a woman, a man or a person of colour, the arithmetic doesn't change. However, I do think that the composition of that crew would be richer and better if it was not just a monotype.

What advice do you have for any young person who wants to become an astronaut?

If you’re in school, study all the science, maths and engineering you can. If you find it's not your easiest subject, consider it like going to the gym and work at it, don't run from it. You can get better.

And I can promise you those skills will serve you extremely well in any walk of life, from lawyer to politician to scientist. But know these skills are the key you must have in your hand to open the door to be a candidate for any of these astronaut selections.

Plus, space agencies also need creative and adaptable people who can encounter the unexpected and come up with a way to solve that problem – to complete the mission and to keep the crew alive. I think the film and book The Martian really showed the type of person you need to be.

On Halloween this year, the much-awaited James Webb Space Telescope – the successor to the Hubble Telescope – will launch. Does it feel like Hubble is passing the torch onto James Webb?

I won't feel bad [when James Webb launches]. I love Hubble and it's just been spectacular what it's done. And it’s lived more than twice its promised lifetime. Everything on Hubble has gotten more reliable, more efficient and more scientifically productive over its 30 years. It is the only scientific spacecraft that has ever gotten better with age in orbit.

I think the torch will pass at some point. But, remember, they’re not identical telescopes. Hubble's basically looking in the visible, ultraviolet and a little bit in the infrared. And the whole point of James Webb is to go much further into the infrared. So even if you look at the same objects with the Webb, you'll be seeing very different characteristics and dimensions of them.

You’ve explored both space and the darkest depths of Earth. But where do you think the most significant discoveries will happen?

I think the most important discoveries and new learnings for the future of the planet will categorically be in the sea.

The ocean absorbs about 40 per cent of the CO2 in the atmosphere. And microorganisms in the sea give us about half the oxygen we breathe – every other breath you take is coming from plankton!

Ultimately, the sea is integrally tied to every other living thing on this planet. And we haven’t reached the kind of understanding of it that we should have. So, from that point of view, that's where the important discoveries will lie.

In terms of the space frontier – going to Mars or taking a look at other planets in our Solar System – it could offer some useful insights about what trajectories our own planet could be on.

We can look at Mars and its history in a way that might help us understand what were the factors that drove its climate change. We could, for instance, find out what made Venus the super intense greenhouse it is today. And then make sure this doesn’t happen to us.