During the opening days of the New Year, while most of us were still getting over the excesses of the festive period, a huge gap in the exploration of the Solar System was being quietly filled. We’d previously sent probes to every planet in the Solar System, had close encounters with comets, landed on asteroids and touched down on one of Saturn’s moons. On New Year’s Day, NASA’s New Horizons probe took photos of Ultima Thule, a Kuiper Belt object more than 6.5 billion kilometres from the Sun.

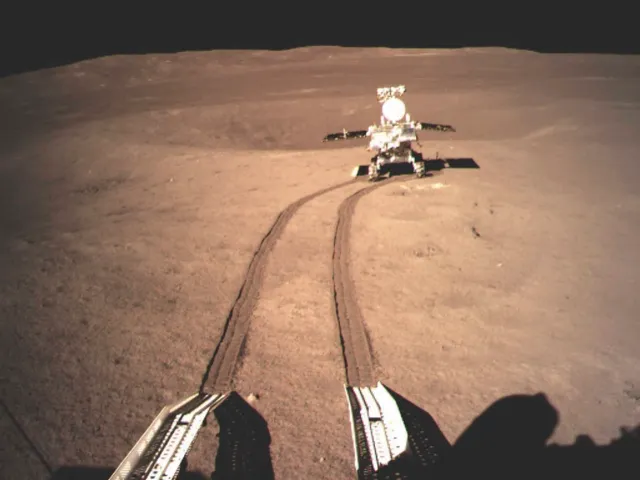

Yet all these things happened before we landed anything on the far side of our nearest celestial neighbour, the Moon. This feat was finally claimed by the Chinese Space Agency with the successful lowering of their Chang’e 4 mission onto the Moon’s surface on 3 January. Just 12 hours later, the Yutu 2 rover trundled down a ramp to imprint its tyre tracks in the lunar dust on the Moon’s far side for the first time. “It’s a hugely significant moment in the history of space exploration,” says Prof Ian Crawford, a planetary scientist at Birkbeck University of London.

Chang’e is named after the Chinese goddess of the Moon, with Yutu being her pet white rabbit that is believed to be visible on the surface of the Moon, much like the man in the Moon here in the West. Chang’e 4 marks a return to the Moon’s surface after years of human indifference, as we’ve strived to explore the rest of the Solar System.

Read more:

- Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway: the next space station will orbit the Moon

- The Digital Silk Road – China’s $200 billion project

Interest in all things lunar began to wane after the Apollo program ended in 1972, with even robotic missions to the Moon’s surface fizzling out by 1976. And so it remained until December 2013, when China landed the first Yutu rover on the near side of the Moon as part of the Chang’e 3 mission, making them only the third nation after the US and Russia to successfully dispatch and land a lunar rover.

But the Chang’e 3 mission wasn’t without its difficulties, as a technical fault hampered the rover’s movement not long after landing. The suspected culprit was more frequent encounters with rocks thanoriginally envisioned. Considering these issues, the Chinese space agency’s subsequent move was a brave one. “It’s quite impressive that their next attempt was on the far side of the Moon,” says Crawford.

Due to the Earth’s gravitational pull, we only ever see one side of the Moon – the other is permanently turned away from us. That’s why Chang’e 4 landed during a new Moon, a time when our side is dark and the far side is completely illuminated by the Sun. Regardless of which side they land on, missions to the Moon have to endure two weeks of cold darkness, followed by a fortnight of intensely bright daylight.

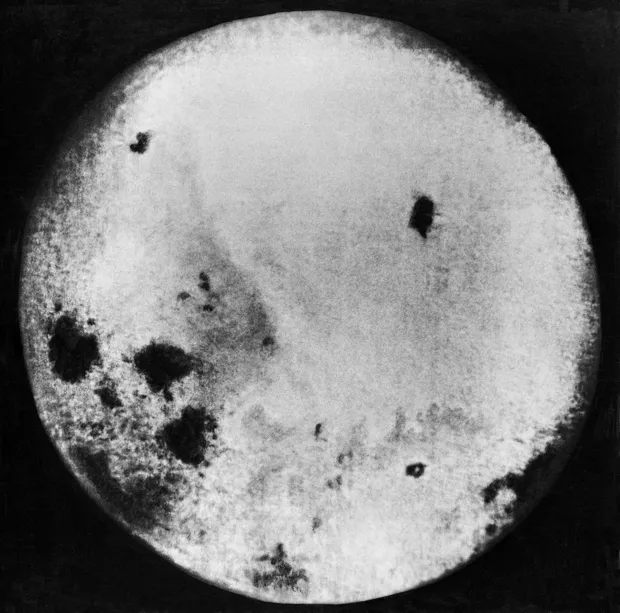

The only way to learn more about the far side is to send probes (or people) around the back for a closer look. While the first image of the far side was taken in 1959, it has taken until now to land a probe on it. NASA rejected the idea of sending Apollo 17, the last human landing mission, there in the 1970s, partly due to the difficulties with communication – the Moon itself blocks direct radio signals with Earth.

Lunar Landing

To get around the communications problems, the Chinese parked the Queqiao (Magpie Bridge) satellite in lunar orbit last year to relay messages back home. Queqiao orbits 65,000 kilometres beyond the Moon and transmits signals back to China and other base stations around the world. This system makes the mission more of an intricate ballet than near side landings. Mission scientists spent four weeks prior to touchdown testing out this crucial relay system. The far side is also far more jagged compared to the relative smoothness of the near side, meaning there are even more potential hazards to avoid on landing.

According to Prof Bernard Foing, executive director of the International Lunar Exploration Working Group, success required “a number of critical manoeuvres including launch, trans-lunar injection, lunar capture, de-orbiting, stabilisation and controlled descent, hazard avoidance, soft landing, the deployment and commissioning of rover and instruments.” It all seems to have worked perfectly. “The whole process was as expected, the result was pretty precise and the landing was very stable,” chief designer Sun Zezhou told Chinese state media shortly after confirmation of success reached home.

Their chosen landing spot was the 180km-wide Von Kármán crater, named after aerospace engineer Theodore von Kármán who made many key advances in the field of aerodynamics in the 20th Century. It’s an impact site superimposed on a much bigger collision scar known as the South Pole-Aitken basin. “It is the Moon’s largest, deepest, and oldest impact structure,” says Foing. Place Mount Everest on the crater floor and its peak wouldn’t be close to poking out over the top.

It’s of extreme geological interest as it could provide clues about the way the Moon formed from debris thrown into space after a small planet collided with the infant Earth. The crater was flooded with lava during the Moon’s early days, meaning the crater floor is incredibly smooth and far less dangerous to land on than elsewhere on the far side. “It was very much chosen with safety in mind,” says Crawford.

The colossal impact that formed the Aitken basin could well have penetrated deep into the Moon’s mantle, exposing deeper basalt material onto the surface. “No one has ever measured the composition offar side basalt before,” says Crawford. Doing so isn’t a certainty, however, as the interesting stuff might have been covered over by the lava flows that flooded the basin.

Like any space mission, Chang’e 4 scientists had to balance risk and reward. So they included another way to get data on the Moon’s subsurface – the Yutu 2 rover carries an instrument called Lunar Penetrating Radar (LPR) that can scan the structure of the lunar far side down to a depth of 100 metres.

Geology is far from Chang’e 4’s only aim. A wide array of other experimental instrument were also crammed onto the back of Chang’e 4 and carried to the Moon. The far side of the Moon is considered by many astronomers to be an ideal place to build a radio telescope. Sheltered from the background hum of the Earth by the Moon itself, any observatory there would be free to make sensitive measurements of faint astronomical radio signals. Chang’e 4 includes an instrument capable of listening to space across a wide range of frequencies. Should its results prove fruitful, Crawford believes it could usher in much more sophisticated radio astronomy missions in future.

However, the majority of Chang’e 4’snon-geological experiments are designed to scope out the possibility of future human missions back to Moon. According to Foing, one experiment called ASAN, “will study how the solar wind interacts with the lunar surface and perhaps even the process behind the formation of lunar water.” The South Pole-Aitken basin is thought to be home to large quantities of water ice – a crucial resource for tomorrow’s Moon dwellers.

Read more:

- 20 of the most amazing moons in the Solar System

- The mindset behind the Moon landing – Richard Wiseman

Would-be astronauts will also be unprotected from the harshness of space. They’d be prone to sizeable doses of radiation from solar storms and cosmic rays generated by stars exploding elsewhere in the Galaxy. The Lunar Lander Neutrons and Dosimetry (LND) experiment, developed in collaboration with Kiel University in Germany, will assess the strength of that dose in the vicinity of Chang’e 4’s landing site.

Life on the Moon

One experiment that fired our collective imaginations when the probe landed was the Lunar Micro Ecosystem. This sealed,18-centimetre cylindrical container contained various seeds and silkworm eggs, with a tiny camera watching to see if these living things could eke out an existence in the harsh, alien environment on the Moon. Soon after the experiment began, cotton seeds sprouted, however, only a day later it was reported that the shoot had failed to survive the freezing temperature of the lunar night. None of the other organisms on board – potatoes, rapeseed, mouse-ear cress, yeast or fruit fly eggs – showed any signs of life and the experiment was called off just a few days into its planned 100-day stint. Despite this, decades from now, humans could look back at this experiment as the beginning of life on the Moon.

Make no mistake that is what China is gearing up for. Their recent launches are following roughly the same pattern as NASA before the Apollo era. First launch satellites to the Moon (Chang’e 1 and 2), then land a rover on the near side (Chang’e 3). This new far side landing is a real show of intent. “The Chang’e 4 mission will advance [their] technical maturity for future robotic and human landings,” says Foing.

China wants to be considered in the same league as the US and Russia when it comes to space exploration. Yang Liwei became the first Chinese astronaut (also called a taikonaut) in 2003. So far, 12 taikonauts have been into space, some of whom were sent to a prototype Chinese space station called Tiangong-1, which remained functioning around Earth from 2011 to 2018 before falling from orbit over the southern Pacific Ocean and reportedly burning up in the atmosphere.

Now, the Chinese have begun the construction of a new, more ambitious orbital outpost in a bid to match the stature of the long-established International Space Station. They hope to have it finished by 2022. What they learn there, combined with the lessons from Chang’e 4, could see China send the first taikonauts to the Moon as early as 2025.

In the meantime, more robotic missions are already in the pipeline. “Their next steps will be Chang’e 5 and 6,” says Foing. The former could launch as early as December 2019 and will aim to return samples of lunar material from the near side. Success will demonstrate that the Chinese can return material from the Moon, paving the way to bring humans back too. “A number of other robotic landers are planned that could build up a de facto lunar robotic village,” says Foing.

Space Race

There is another potential advantage to be gained from the recent Chang’e missions. No other country has landed anything on the Moon since the 1970s. Having readily available technology to do so could place China in the lead to exploit the Moon’s natural resources. By analysing the composition of the lunar far side, they could gain valuable information about the kind of treasures potentially on offer. The Moon is already thought to contain significant amounts of helium-3, which is a chemical that’s exceedingly rare on Earth. What else could they find squirrelled away in these unexplored rocks? Could a modern space race be triggered as superpowers compete once again for off-Earth supremacy?

Some quarters are nervous about what it could mean for the potential Chinese militarisation of space. The country is party to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which forbids signatories from placing weapons of mass destruction on the Moon. However, China has previously flexed its space muscles, most notably when it destroyed one of its own weather satellites in 2007 using a missile fired from the ground. While other space agencies have been quick to congratulate the Chinese on their latest success, and talk openly about potential joint projects, it remains to be seen whether the future will be more about competition or cooperation.

- This is an extract from issue 332 of BBC Focus magazine - Subscribe here