Is seeing a shooting star on your 2022 wish list? Good news: the Geminid meteor shower, one of the biggest showers of the year, will send streaks of light across tonight’s sky.

The shower may have just peaked (on the night of 13 to 14 December), but you can still expect to see many shooting stars per hour.

How can you improve your chances of catching one? What’s the best way to photograph a shooting star? And what is a meteor shower, anyway?

All good questions, and all of them have been answered below with the help of Dr Darren Baskill, astronomy lecturer at the University of Sussex.

Remember, if you’re looking for more stargazing tips, be sure to check out our astronomy for beginnersguide and ourfull Moon UKcalendar.

When can you see the Geminid meteor shower 2022 in the UK?

The shower peaked on the night of 13-14 December, with around 150 meteors per hour visible in good conditions.

You can see shooting stars from the Geminid meteor shower until 20 December, if you’re in the UK and around the northern hemisphere.

The meteors can be seen at any time of night, but the darker it is, the better your visibility.

How many meteors will I be able to see in the UK?

On 13-14 December, the zenith hourly rate, or ZHR, of the meteor shower was 150, meaning you would be able to see that number every hour in perfect conditions.

“In reality, due to light pollution, you’ll probably only get to see 20 an hour at this peak. However, that still means you’ll hopefully be able to catch one every few minutes,” says Baskill.

After the Geminid’s peak, the later the date you try and spot a meteor, the fewer you are likely to see per hour.

How can I see the Geminid meteor shower?

The Geminid’s meteors will appear to originate from the same place in the night sky: the constellation of Gemini (hence ‘Geminid’).

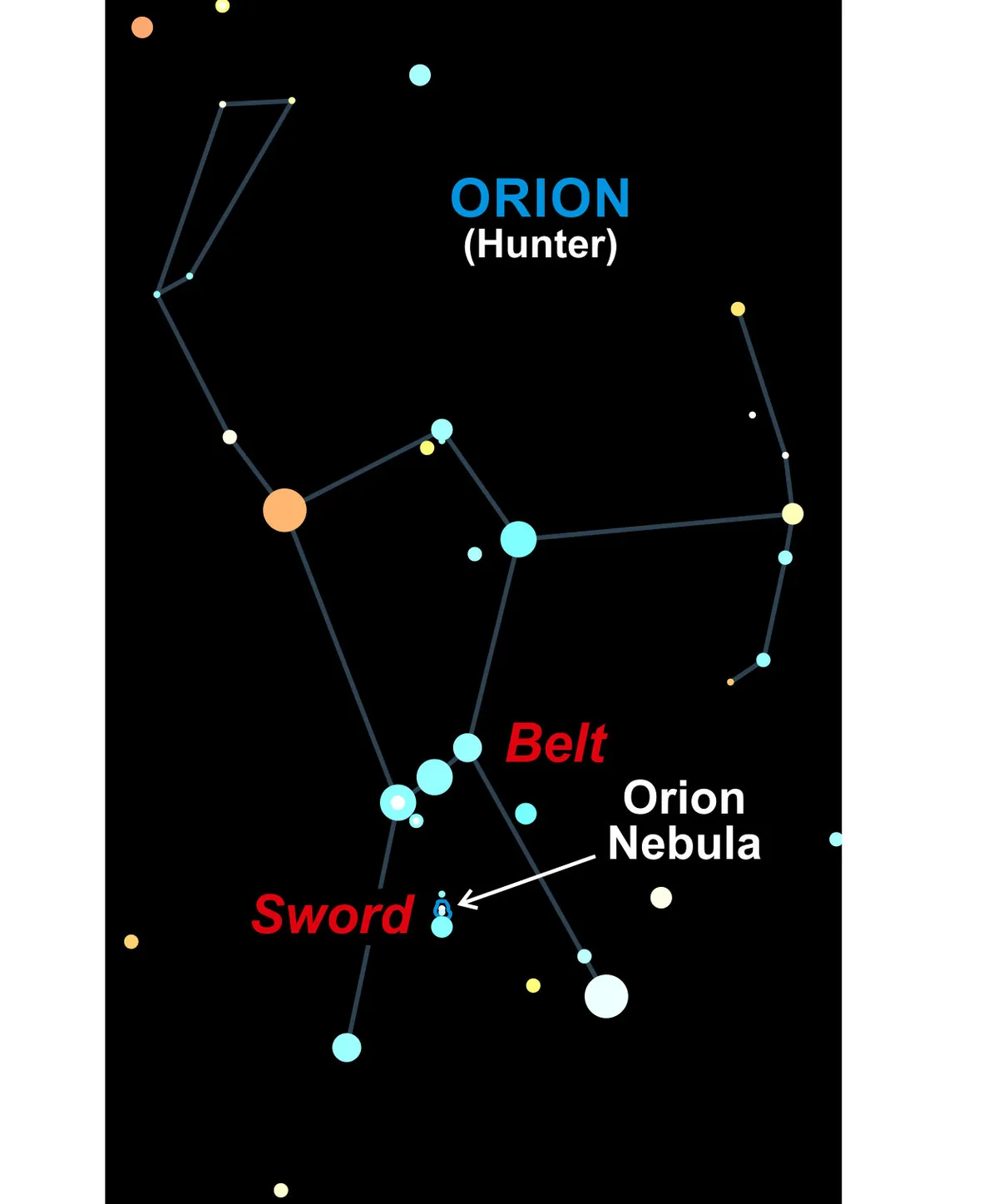

Fortunately, finding Gemini is fairly easy. To start, you need to locate Orion, a constellation including three stars in a row making up Orion’s Belt (check out ourbeginner’s guide to astronomyif you need a refresher). From there, look up and to the left and you’ll see two bright stars, Castor and Pollux from the constellation Gemini.

If you’re struggling, we recommend using an app such as Skylite (available for free on AndroidandAppledevices).

Still can’t find Gemini? Don’t worry – you’ll still be able to see shooting stars aplenty. “Although most meteors will come from this point, they can appear anywhere in the night sky. This means, ideally, you should be looking at as much of the night sky as possible,” says Baskill.

“You can get really bright ones overhead or all over the horizon. If in doubt, just look up!”

Unfortunately, this year, the Moon will be mostly full (in its waning gibbous phase) during the shower, which will reduce the number of meteors you see. Also, white snow and frost on the ground reflecting light will reduce visibility.

The good news is that you should still be able to see plenty regardless. “Yes, the Moon will be a hindrance. But one of the great things about this shower is how bright and slow-moving the meteors are – they’re the brightest of the year. You can see some spectacular fireballs – I have seen some amazing ones from inside in the past!” says Baskill.

That’s right: shooting stars may be seen from your upstairs window. You may not see as many from inside your house (visibility will be better outside in a dark place away from major lights), but this will mean avoiding dangerous icy conditions outside.

“Outside, you’ll see one every few minutes, but inside – depending on your luck – you may see one every five to 10 minutes,” says Baskill.

If you are viewing the shower from indoors, make sure to turn your lights off and let your eyes adjust to the dark for at least 20 minutes. You can go that long without checking your phone, right?

Read more about meteors:

- Meteor, asteroid and comet: What’s the difference?

- How can we tell that a meteorite has come from a particular planet?

How can I photograph a meteor shower?

If you’re trying to capture a shooting star with a high-end camera, you need to set up your device in the correct way.

“Meteors are relatively quick, meaning you’ve got to have your camera on very sensitive settings to make sure that a brief moment of light lands on your camera chip,” says Baskill.

This means a very high ISO setting of 3200 or more is required, plus a low f-number (3.2 to 4) to open your lens and allow plenty of light in. As for exposure time, set to at least three seconds.

Attached to a tripod, you want to take as many photos as possible, setting your camera to continuous mode. “I’ll often take an image every 10 seconds for hours to ensure a good one!” says Baskill.

Be also careful not to mistake a meteor for a satellite. “There will be lots of photos appearing over the next few days of what people think are meteors but are actually satellites. The difference is that satellites have a symmetrical trail, whereas meteors don't, due to them exploding at the end of their journey through the atmosphere!” explains Baskill.

“A satellite takes five minutes to travel across the night sky – but from a single photograph, it is impossible to tell!”

What about if you’re just using your phone? Well, it’s a difficult, but not impossible, task. You will need to download a long exposure app, such as NightCap (Apple, free) or Night Camera (Android, free).

It’s best to turn off your flash and HDR (High Dynamic Range), avoid using the zoom function and keep the camera as steady as possible.

What is a meteor shower anyway?

A meteor shower happens when Earth collides with small pieces of debris from an asteroid or comet. Although this debris is small (the size of a grain of sand in most showers), it creates bright streaks in the sky as it travels at extremely high speeds.

The debris that hits Earth during the Geminids originates from the asteroid 3200 Phaethon. “This asteroid leaves behind much bigger particles floating in space than most comets. This means the shooting stars it creates are bigger and brighter than usual,” says Baskill.

About our expert, Dr Darren Baskill

Dr Darren Baskillis an outreach officer and lecturer in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Sussex. He previously lectured at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, where he also initiated the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.