Hot off the heels of the Lyrid meteor shower is the Eta Aquariid meteor shower, which is expected to hit its peak later this week.

So, what is the best way of making sure you see the Eta Aquariid meteor shower? What causes it in the first place? And when exactly should you look out for it? Answers to all this, and more, are below.

If you’re looking for more stargazing tips, be sure to check out ourastronomy for beginnersguide and our UKfull Moon calendar to make the most of the night sky. For a full roundup of this year's meteor showers, we’ve got all the essentials listed in our meteor shower calendar.

When can you see the Eta Aquariid meteor shower 2022 in the UK?

The Eta Aquariids began on 19 April 2022 and will be visible until 28 May 2022. The meteor shower peaks on 6 May, and we will be offered decent viewing conditions thanks to dark skies from a waxing crescent Moon that sets in the early hours at 1:39am.

The best time to view the Eta Aquariids in 2022, will be between midnight and sunrise at 5:23am on the morning of the 6 May.

However, if you miss the Aquariids at their peak, meteor spotters are often treated to very nice displays on the nights around the peak, and they’ll be visible until the end of May.

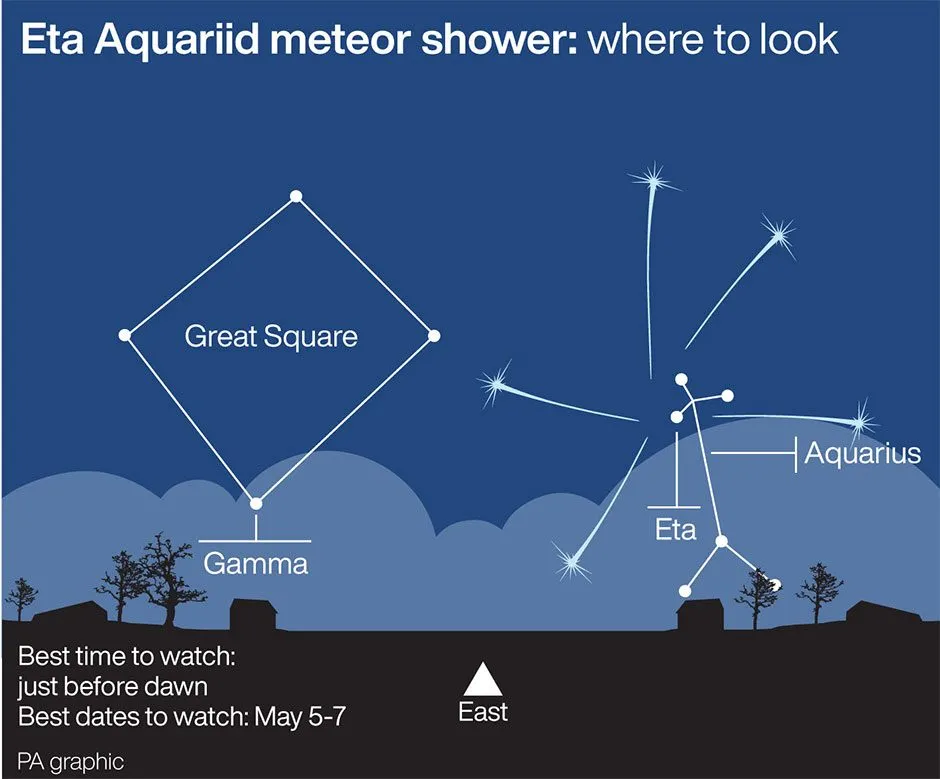

Where to look

The Eta Aquariids are visible from both hemispheres, although viewing favours the Southern Hemisphere. This is because the radiant – the point from which the meteors appear to originate – is near to the celestial equator, close to the Water Jar asterism in the constellation Aquarius.

For those of us in the UK, this means that the meteor shower will appear at a low altitude in the sky, so we may be treated to meteors that appear to shoot up from the horizon. As dawn approaches, the radiant will climb higher in the sky, giving us a better opportunity to see particles of the most famous comet.

To find the radiant, locate the two stars in the Great Square of Pegasus, Scheat and Markab - this is the top-most star and the right-hand star in the diagram below, as viewed before Sunrise on the 6 May.

Draw an imaginary line between these two stars and extend it for about the same distance again. Near here is the faint star Eta Aquarii, marking the apparent position of the radiant. If you’re having trouble picking out Eta Aquarii, you could always use a star-gazing app to help you out.

This radiant hasn’t changed much since semi-regular observations began of the Eta Aquariids back in 1863 when Hubert A. Newton noticed a coincidence in the dates of a series of showers in historical records. This means we can look forward to a similar viewing angle every year.

How many meteors will you be able to see?

At its peak on 6 May 2022, the Eta Aquariid meteor shower has a maximum zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) of around 60 meteors per hour. However, the ZHR assumes ‘perfect’ conditions: clear skies and no light pollution, as well as a radiant that is directly overhead. Given that the Eta Aquariids have such a low-altitude radiant, it’s unlikely we’ll see this many.

That said, around one-quarter of these are expected to leave persistent trains in the sky, so if you have a tally counter to hand, this is a fun way to record how many you see!

If we were able to view this meteor shower during the daylight hours, the radiant is highest in the sky just before midday. Using radar (radio-echo) techniques, the Springhill Meteor Observatory near Ottawa recorded as many as 500 meteors per hour at the shower’s peak between 1958 and 1967.

Where do the Eta Aquariids come from?

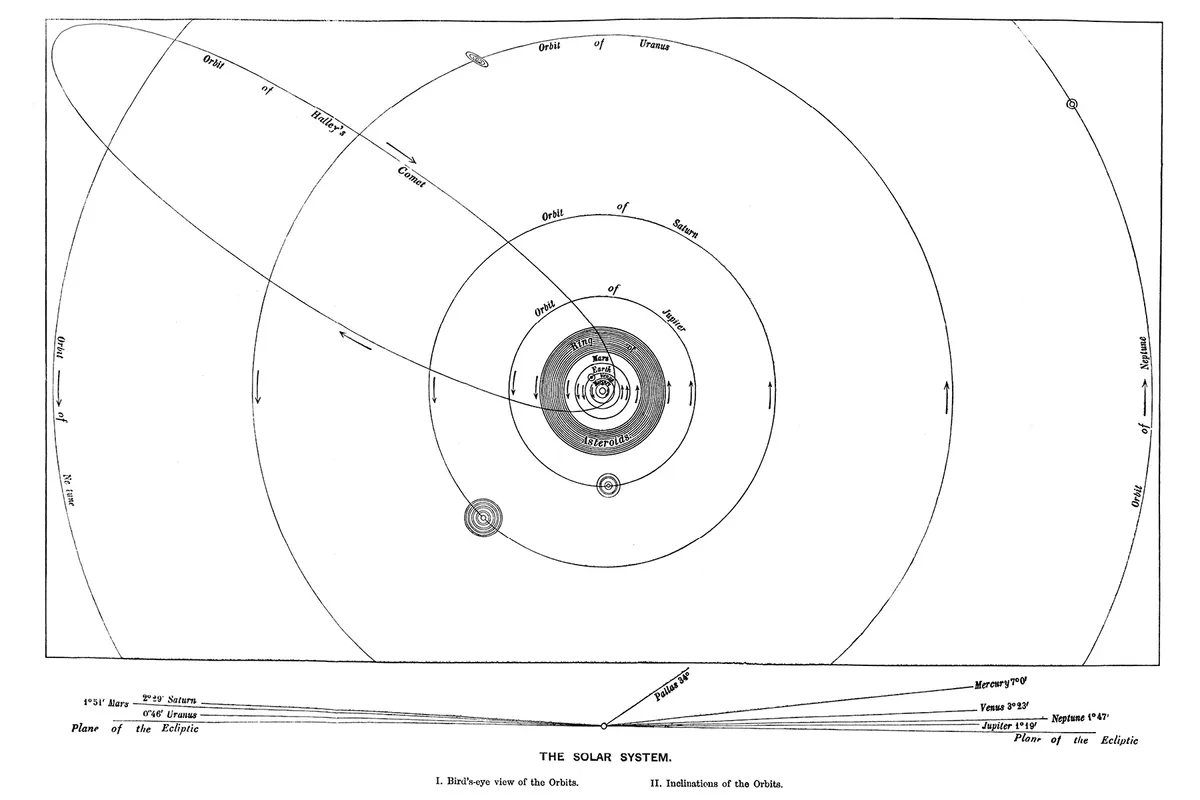

Like the Orionids in October, the Eta Aquariids are the result of debris from 1P/Halley, more commonly known as Halley’s Comet.

Halley’s Comet is a crumbly, ‘dirty snowball’ comet, made of a mixture of volatile ices and dust. It’s been making its journey around the Sun for at least 16,000 years, leaving a trail of debris along its orbit over the millennia. Its highly elliptical orbit stretches out around the Sun like an elongated oval, extending beyond the orbit of Neptune at its furthest point.

Every time the Earth’s orbit crosses this trail of debris, particles enter our atmosphere and disintegrate, leaving bright streaks in the sky.

Halley’s Comet is in a retrograde orbit, meaning it orbits the Sun in the opposite direction to Earth (and the other planets). Meteoroids from Halley’s Comet enter Earth’s atmosphere at relatively fast speeds of around 66km/s and will appear as fast streaks, the brightest leaving long-lasting trains.

As a result of this retrograde orbit, there are two meteor showers associated with Halley’s Comet. These are the Eta Aquariids in early May, and the Orionids in late October, as Earth intersects with the ‘other side’ of Halley’s orbital path around the Sun.

When will Halley’s Comet return?

Halley’s Comet was last seen gracing our skies in April 1986 and will return in 2061 during its 76-year orbit. It’s the only (currently known) short-period (less than 200-year orbit) comet regularly visible to the naked eye, and the earliest recorded observation was by Chinese astronomers in 239 BC.

Where is Halley’s Comet now?

Right now, Halley’s Comet is approaching its aphelion point, the point in its orbit furthest from the Sun, and it is currently in the constellation Hydra. On 6 May 2022 when the Eta Aquariids peak, it will be 5,251.59 million km from the Sun. It’s predicted to reach aphelion in December 2023.

Viewing tips

If you can, find an area away from light pollution. Night temperatures on the 5/6 May are expected to be fairly mild – around 10 to 11°C with a light cloud and low chance of precipitation here in Bristol – but be sure to check your local weather forecast. Even so, be sure to wrap up warm, as you’re probably not going to be moving around much.

Lie back in a reclining chair, hammock, or on a blanket, and let your eyes adjust to the darkness for around 10 to 20 minutes.

After a while, and with a little patience, you’ll find you become more accustomed to seeing the meteor trails as they streak across the sky. Try not to look at other bright sources of light (such as your phone) during this time. If you do, use a red filter.

Read more about space rocks: