Your book is calledYou Are Here: Around the World in 92 Minutes. Why 92 minutes?

When you’re orbiting the Earth, the speed with which you go around the world depends on how far from the world you are – like a ball on the end of a string. If you’re as far away as the Moon, it takes about a month, but the closer you get, the faster you have to go, like a shorter and shorter string. The altitude that astronauts normally fly at on board the International Space Station (ISS) is only around 400 km, and at that altitude you go around the world every 92 minutes.

During your time in space you were regularly tweeting photos from the ISS. How many photos did you take in total?

I flew in space three times – once to the Russian space station MIR and twice to the International Space Station. Over those three flights, I took about 45,000 photos. There’s no time on orbit to review all your photos – you take a bunch, download them to Earth, and then they sit in a vault. So it was really lovely to have a chance back on Earth to go through the photos and try and pick out the ones that show the Earth for what it truly is. I whittled it down to about 150 photos for the book.

When you were choosing your favourite photos, what were you looking for?

I was looking for two things primarily. One was to be able to tell the story of the whole Earth, not just focusing on one country or one continent. The second was that I wanted a mixture of photos that showed the Earth as an immense, natural, ancient and extremely unique place, but also as a home for seven billion of us, with the parts where we’ve made changes on the surface. I wanted to show a true reflection, to the best of my ability, of what the world really looks like out of the window of a spaceship.

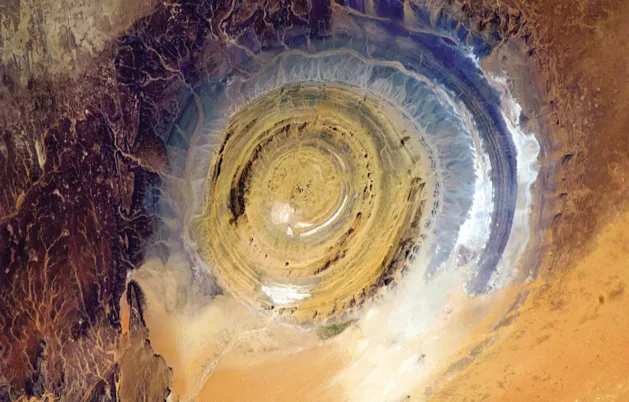

"The Richat Structure in Mauritania, also known as the Eye of the Sahara, is a landmark for astronauts. If you’ve been busy doing experiments and haven’t looked out the window for a while, it’s hard to know where you are, especially if you’re over a vast 3,600,000-square-mile desert. This bull’s-eye orients you, instantly."

The quality of the photos is stunning – what equipment were you using?

NASA puts cameras on board the space station. They don’t last very long because the radiation level is so high up there it actually damages the sensors in the camera, but they’re standard, good-quality Nikon SLR cameras.

We have a variety of lenses. When you’re looking at the book, if you see an image where the curve of the Earth is exaggerated, that’s a fisheye lens. If it looks like a naked-eye picture, then that’s a 50mm lens, and if you’re seeing real detail, then that’s a 400mm lens. Those are the three main lenses that I used to see the planet.

Has viewing the Earth from space changed your perspective on our planet?

Of course – most people see the world in the area they’re familiar with, and then the rest of it is sort of theoretical, or a distant unknown. To go around the world thousands of times, like I have, you really get to know the world for what it truly is, with its infinite variety and its amazing ability to self-heal, but also the damage that we’re inflicting to it.

But that didn’t make me pessimistic. Even though there are seven billion of us on the surface, we all tend to crowd into the same little spots, so much of the world is still dark and natural. We’re definitely having a significant effect on the world, but the world is also vast and ancient. I think that’s an important perspective for us to have.

Was there anything that looked different from what you expected?

[The Earth] is immensely more beautiful than you would think. You picture in your mind that it looks like a blue globe, but you’re close enough on the ISS to really pick out the detail with a decent-sized lens – the textures and the colours.

If you’re up in space for months, the seasons change – you get winter and summer swapping ends of the planet, and that constantly refreshes it. It’s just so drop-dead gorgeous to see the volcanoes, the sunrises and the misty valleys, the sun glinting off the various parts to bring out details and shadows and colours.

I really like the human element to your photos – the way you pick out certain landmarks or features that look like animals or faces. Is that human perspective something you set out to achieve?

When I lie in a field and look up at the clouds, my mind invariably wants to turn them into something I recognise, like a horse or a face. Your mind does the same thing from orbit looking at the world. I think the difference between a robot and a human taking a picture is the sense of play and wonder. The human judgement makes a big difference.

Some [images] just make you laugh, like there’s an exclamation point of an island off the coast of Turkey. I just couldn’t believe it when I saw it – it’s like a cartoon. And there’s this gigantic volcano on New Zealand’s North Island where the combination of its natural shape plus the way the farmers have worked around it has created this perfect circle with an eyeball in the middle, staring up at you, unblinking.

Your final mission to the ISS was in May last year. Do you miss going into space?

I am so self-aware of the luckiness that I’ve received. I worked at it my whole life, but I was also very fortunate to have flown in space three times, commanded the ISS, and seen the things that I’ve been allowed and trusted to see. So I don’t miss it - I just see it as a wonderful series of events in my life so far.

Now I teach at university, I’m writing books, I work with public schools, and this past weekend I debuted a whole suite of music that I wrote on the ISS with the Windsor Symphony Orchestra in Canada.

The cover of

[David Bowie’s]

“Space Oddity” you made while on the ISS was a massive hit. Are you still releasing music back here on Earth?

Very much – I wrote asong with my brotherthat was released back in July, and a song with the musicianEmm Gryner. This concert series with the Windsor Symphony went really well – it was a combination of talking about spaceflight with imagery behind the orchestra and an original suite of music that was inspired by being there. It’s another way to tell what’s at this point still a very unusual human story, and with that human story a unique perspective on ourselves.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard