On the evening of 20 July 1969, an age-old dream was about to be fulfilled: mankind was on the verge of touching the Moon. With the words: “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed,” Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong at last confirmed the success that everybody had hoped for. Amid that elation, it would be impossible to guess that in just another three years’ time, the dream of walking on the Moon would slip beyond our reach indefinitely.

Throughout the night of 20 July, reporters were listening to every word of radio dialogue. Yet somehow, an intriguing comment from mission control’s capsule communicator (‘capcom’), Charlie Duke, went almost unnoticed at the time: “Roger, Tranquility, we copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

Read more about the preparations for the Apollo space programme:

- Ladies who launch: the women behind the Apollo Program

- Small steps: How NASA prepared for the first moonwalk

- In pictures: USA vs USSR - the race to the Moon

Why had mission control been holding its collective breath? Because Apollo 11’s lunar module, the Eagle, had edged close to disaster as it plunged towards the lunar surface. During its final approach, a warning light on Eagle’s display suddenly started flashing. “Program alarm,” said Armstrong. “1202,” Aldrin confirmed.

Mission abort?

At mission control, 26-year-old Steve Bales was sitting at the guidance console (‘guido’), monitoring Eagle’s navigation systems. “What’s a 1202?” flight director (‘flight’) Gene Kranz demanded to know. Bales was in the spotlight. Eagle was rushing towards the Moon and the computer was saying that something was wrong. Then another warning started flashing, this time it was a 1201. Bales needed a few seconds to think. “Stand by,” he replied, trying to buy time. But Armstrong needed an immediate answer. “Give us the reading on the 1202 alarm,” he said. In astronaut-speak, he was asking if he and Aldrin should abort the landing.

Bales had no time left to think. Making the bravest and possibly most reckless decision of his life, he announced into his headset: “We’re go on that alarm.” This was a signal for the astronauts to continue their descent.

Kranz was surprised, but he trusted his controllers and let the decision ride. Eagle plunged onwards toward the Moon. The rules on safety were clear; Bales should have asked Kranz to call off the landing, but he didn’t believe the alarms. The computer was still feeding reliable information about speed and altitude to the astronauts’ control panels, and the descent was proceeding more or less according to plan.

Now, decades later, Bales still isn’t sure about the decision he made in that moment. “Nobody really knew what was causing the problem and I couldn’t be 100 per cent sure that the judgement I was making was okay. It was based more on instinct than hard facts,” he recalls.

Just as Bales was recovering from the 1202 scare, capcom Charlie Duke radioed a terse warning up to the Eagle’s crew: “60 seconds.” Listening to the dialogue tapes, it’s impossible to tell that anything was wrong, because of the cool nature of space-flight professionals, but in technical shorthand Duke was saying to Armstrong, “You only have a minute’s worth of fuel left.” In most of the simulations that Armstrong had performed in training, he’d made it to the surface with plenty of fuel to spare by this point. So what was happening?

Everyone at mission control was nervous. Duke called out another warning: “30 seconds.” Standing behind him, chief astronaut Deke Slayton said softly, “Shut up Charlie, andlet ’em land.”

Kranz and his team then saw something even more worrying on their screens. With less than 30 metres remaining before touchdown, the lunar module was pitching forward and skimming over the lunar terrain at 55km/h. Had NASA’s two best astronauts lost control of their ship?

Eagle’s engine was about to sputter and die. The instant it did so, Armstrong would have only a few seconds to pitch it upright again, using the small thrusters on the ascent stage.

Then the landing legs might withstand the shock of an unpowered drop on to the lunar surface. Alternatively, he could hit the ‘abort’ switch and blast the ascent stage back into space. If anything went wrong now, the lives of the two astronauts would depend on a split-second choice between two equally unwelcome options.

Read more about the Apollo 11 crew:

- Neil Armstrong: Apollo 11 mission commander

- Buzz Aldrin: Apollo 11 lunar module pilot

- Michael Collins: Apollo 11 command module pilot

Another 10 seconds crawled by. At last, Aldrin radioed, “Contact light. Mode control to auto. Engine arm off.” Those were the first words spoken by a human on another world. Sadly for Aldrin, we prefer to remember Armstrong’s words a few moments later: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Duke’s response, “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue,” was almost lost among the whoops of delight in mission control. Kranz had tears in his eyes but forced himself to stay calm. Now that Armstrong and Aldrin were on the Moon, the first thing they had to do was get ready to leave in a hurry. “Everybody settle down and check for Stay-No-Stay!” Kranz shouted to the noisy controllers around him. It wasn’t yet safe to assume that the astronauts could remain on the surface.

What if the lander had been damaged on touchdown? What if one of its four legs was resting on a boulder and suddenly slipped off? Armstrong and Aldrin immediately prepared their switches for an emergency ascent. They had been on the surface for a full two minutes before Kranz finally decided that Eagle could stay where it was. When at last he lifted his hand off the desk of his console, he found it was all but glued in place by the sweat that was pouring off him.

Armstrong sounded apologetic. “Houston, that may have seemed like a very long final phase,” he explained. “[But the guidance computer’s automatic targeting system] was taking us right into a crater with a large number of boulders and rocks.” He had needed those precious extra seconds to manually nudge Eagle forwards a few hundred metres until he could find a safe place to land.

No apology was required. “Be advised, there are a lot of smiling faces in this room,” said Duke. “There are two smiling faces up here also,” replied Aldrin.

“And don’t forget one in the command module,” said Mike Collins, sitting alone in theorbiting Columbia.

The world is watching

Approximately 600 million people – one-fifth of the global population at the time – watched the subsequent moonwalk on television. In the US and other rich countries, many families had their own TV sets. In poorer nations, people huddled around TVs rigged up in community halls, or even in the streets.

We take it for granted today that we should be able to talk to astronauts or send instructions to space probes with relative ease. But in the 1960s, the communications network for the Apollo programme was almost as impressive as the mission itself. Because of the Earth’s constant rotation, communication with lunar astronauts required three major radio dish stations spaced at approximately 120° intervals around the planet: one in Goldstone, California; one in Australia, near Canberra; and one at Robledo de Chavela, near Madrid. ‘Passive’ radio astronomy dishes at other locations also listened in but could not transmit anything back to Apollo.

On the night of the moonwalk, BBC coverage of events from mission control was relayed from Houston to a radio dish in Maryland, then bounced off the Intelsat III satellite, in geosynchronous orbit above the Pacific, and down to a radio receiving dish at Goonhilly in Cornwall, from where it was fed to the BBC in London. The first radio dish on Earth to receive pictures from the Moon was the Australian station at Honeysuckle Creek near Canberra, much to the delight of its staff.

Many media commentators thought that the Apollo programme was a waste of money while so many people around the world remained poor. But when Armstrong and Aldrin finallymade it onto the lunar surface, even the sternest critics paused to acknowledge a unique and uplifting event in the history of our species.

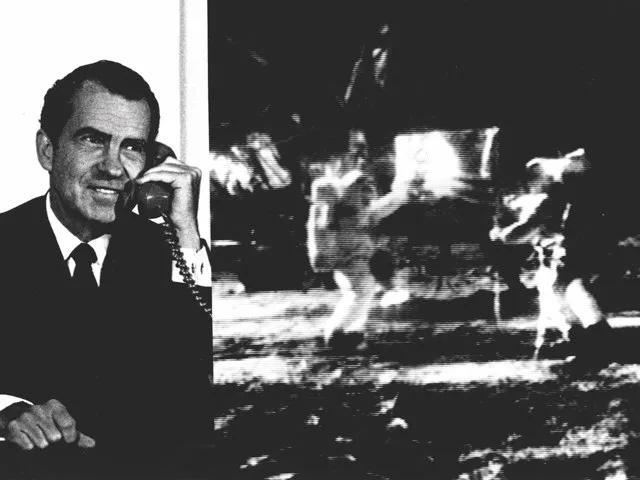

During the moonwalk, President Richard Nixon spoke to the astronauts, basking in their reflected glory even though he had done nothing to make Apollo possible. In fact, behind the scenes, Nixon was shutting down the Saturn V factories and curtailing NASA’s budgets. By the Christmas of 1972, the lunar missions would be over.

Course for home

When Eagle’s ascent stage flew back up from the surface and safely re-docked with the orbiting command module Columbia, Collins learned just how close Armstrong had come to running out of fuel. “Were you really down to 20 seconds?” he asked. “That’s plenty of time,” Armstrong replied.

For safety’s sake, NASA insisted that a homecoming command module had to survive re-entry without using the service module’s engine to slow it down, just in case anything went wrong with the propulsion systems, leaving a crew stranded in space. After blasting out of lunar orbit with a final engine burn that couldn’t be dispensed with, Columbia’s return trajectory was essentially a three-day fall towards Earth at ever-greater speed. The command module hit the atmosphere at 40,000km/h.

Listen to podcastsabout the Apollo Programme:

- Science Focus Podcast|Why is the Moon landing still relevant 50 years on? – Kevin Fong

- Science Focus Podcast|The mindset behind the Moon landing – Richard Wiseman

- Radio Astronomy Podcast|Talking Apollo moonwalkers with author Andrew Smith

- History Extra Podcast | The race to the moon with historian Kendrick Oliver

NASA tried to portray the hazards of Apollo missions as routine and predictable. This cautious public relations strategy backfired, however, as some of the drama got lost amid the bland press statements. After Apollo 11, the public soon grew bored of space exploration. Nevertheless, it’s impossible not to appreciate just how heroic and extraordinary that mission really was.

As for Steve Bales, he collected a certificate from NASA and a medal from President Nixon, for ‘saving’ the Apollo 11 mission. He often wondered what they might have given him if he’d been wrong.

Post-flight analysis revealed that the lunar module’s computer glitch (one that could have pitched America into the greatest public relations disaster in modern history) was similar to the problems encountered by Apollo 10, which Houston thought it had resolved before launching Apollo 11. The lunar module’s computer was struggling to handle data from two radars simultaneously and came close to overloading. Close, but luckily, not quite over the edge.

Mission Control: Houston

The locations of key personnel in mission control throughout the Apollo 11 mission

- PAO The public affairs officer was the ‘voice of mission control’ for viewers and listeners around the world.

- Mission Director The person in overall charge of the Apollo programme.

- Director of Flight Operations Mission control’s liaison with NASA’s senior management.

- Department of Defense Representative Military liaison officer to coordinate recovery ships and aircraft.

- O&P The operations and procedures officer monitored the application of mission procedures at every stage.

- INCO The integrated communications officer monitored communications systems aboard both the command and lunar modules.

- FAO The flight activities officer kept track of the mission timeline and planned unscheduled crew activities.

- FLIGHT The flight director was in charge of every aspect of the mission, from clearing the tower to splashdown.

- NETWORK The network controller was in charge of the ground stations in NASA’s Manned Space Flight Network.

- SURGEON The medic that monitors the crew’s health and their reactions to the space environment.

- CAPCOM The capsule communicator was the only person in mission control with a direct line to the Apollo 11 crew.

- EECOM The electrical, environmental and consumables manager monitored the spacecraft’s fuel cells, electrical and life-support systems.

- TELMU The telemetry, electrical and EVA mobility unit officer was in charge of systems aboard the lunar module, including the astronauts’ spacesuits.

- CONTROL The control officeroversaw guidance and control for the lunar module.

- BOOSTER The booster systems engineer monitored the Saturn V from launch until it left Earth orbit.

- RETRO The retrofire officer tracked retrorocket firings, including those that returned Apollo 11 to Earth.

- FIDO The flight dynamics officer assessed flight trajectories and planned major spacecraft manoeuvres.

- GUIDO The guidance officer tracked all the data from Apollo’s on-board navigational systems.

- Maintenance and Operations Supervisor The NASA engineer in charge of monitoring and ensuring the smooth running of mission control’s computers.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard