PAST

Pompeii is one of the must-see sights of Italy alongside Herculaneum, a town that also perished when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79AD. The city is important to us because of the way Vesuvius both destroyed and preserved it, but in the 1st Century AD it had little special significance. If there were any tourists, they were more likely to be strolling the beach at Herculaneum – and perhaps hoping for a glimpse of Emperor Caligula at his luxury villa – than in the markets or industrial wharves of Pompeii.

Locally, however, Pompeii was an important inland port, a place of trade, industry and business, famed for its fermented fish sauce. Its people were a mix of wealthy elite, professionals and slaves. Inscriptions attest to bakers and bath-attendants, grape-pickers and prostitutes. The recent decipherment of writing tablets from Herculaneum suggests that over half its population were slaves or freed slaves. It reveals the true extent of this infamous aspect of Roman society.

There is no reason to think Pompeiians were anything other than typical Roman citizens, so their remains can probably speak for many across Italy at the time. While they suffered the diseases and discomforts that still affect us today, in general their health beyond childhood (higher infant mortality is likely) was not greatly different from our own. However, one study suggested an important exception to this rule: the state of teeth and jaws point to poor dental hygiene.

The slopes of Vesuvius were known for its fertile soils and wine from Pompeii was an important export – at least one wine jar made it all the way to England. But people were less aware of the volcano’s dark side. The city had been badly damaged by severe earthquakes 15 years before the eruption. Yet none of this was connected to volcanism. There was nothing to fear…

PRESENT

Since its discovery in 1748, people have been digging up Pompeii for over 250 years. You might think there was little more to learn, but as Paul Roberts, curator of the British Museum exhibition says, if there’s one thing that recent research at Pompeii and Herculaneum has made clear, it is that “It’s not so clear”. We are far from really understanding what made Pompeii tick.

Modern science and archaeology have replaced the old-style treasure-hunting for fine artefacts and wall paintings. In the process, everyone has realised how much knowledge was lost through earlier work – and how much more we can learn now. The excavation of houses still sealed under ash has stopped. Yet researchers from up to 20 nations are engaged at Pompeii, recording and analysing their predecessors’ excavations, bringing new science to old finds and making new discoveries as they try to save and restore what remains.

Take gardens. Early students had questioned whether the lush gardens pictured in wall paintings could have been real. But detailed examination of those parts of Pompeii that were not built over revealed how much of the town had been green, from kitchen plots to orchards and vineyards, as well as impressive formal gardens with pools and fountains. Recent work has proved the use of a huge variety of trees, flowers, herbs and vegetables through the study of wood, pollen, seeds and other plant remains.

It has been estimated that at least a fifth of the entire town was green space. It is microscopic finds like this that are now helping to show what was happening in Pompeii, from fish-salting to horse-stabling. A recent excavation found the remains of a tethered mule, lying slumped against its feeding trough surrounded by bedding and fodder. Subsequent analysis of this revealed grasses, wayside plants, cereals, olives and walnuts. Recovering such detail is slow work. A University of Cincinnati project uses iPads in the trenches to keep up with the huge amount of data its excavations produce.

The body casts at Pompeii are justly famous, but it is the skeletons themselves that are now proving to be the more informative. Studies that include medical scanning of casts, and searches of centuries of museum collections have shown it was not just the weak and infirm who failed to escape Vesuvius’s wrath. In just one house, 13 healthy people died: their ages suggest grandparents, parents and their children, one of whom was a pregnant teenager.

FUTURE

Vesuvius made a mess of Pompeii, but now it faces a second death. Walls, paintings and floors meant to last only a few decades are exposed to the feet and fingers of millions of tourists and torrential rain. Pompeii’s great need is conservation, but the task is daunting. Restoring and protecting over 15,000 buildings, five acres of wall paintings and uncountable quantities of artefacts might seem impossible, but this is where developments in archaeology can help.

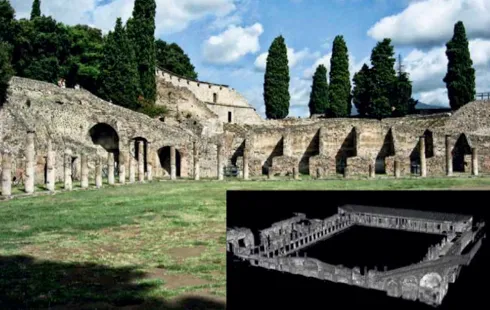

All teams now working at Pompeii and Herculaneum use digital scanning and recording. Not only are these techniques cost-effective, but the results are more precise than was possible with pen and paper. The American Pompeii Quadriporticus Project shows what can be done.

This team of archaeologists have recorded a large rectangular open space enclosed by a colonnade backed by small rooms – probably a gymnasium – with 3D laser scanning, photogrammetry (determining the geometric properties of an object from images) and masonry analysis. The result is a convincing 3D image. Digital manipulation of the completed model will allow it to be studied in ways that are all but impossible on site. It will be a virtual archive, a form of digital conservation easier to preserve than the original.

These records can be used to print physical replicas in 3D – even full-scale models that could be opened to tourists, while the real ruins are saved for posterity. Such a replica has recently been completed of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, to stunning effect.

Life and death in Pompeii and Herculaneum shows at the British Museum from 28 March - 29 September 2013.

Mike Pitts is a writer and the editor of British Archaeology magazine. This article first appeared in the March 2013 issue of Focus.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard