In one of my favourite scenes in the American sitcom The Big Bang Theory, Sheldon Cooper and his girlfriend Amy are playing the guessing game ‘Who am I?’ When Amy offers the clue “He’s a poor man’s Sheldon Cooper,” Sheldon guesses immediately: “Oh, Tesla.” The episode plays with Sheldon’s admiration for Nikola Tesla that forms a running theme through the series.

It’s a fascinating reminder of what Tesla means now. When Elon Musk called his electric car the Tesla he was buying in to this Tesla story too. We imagine Tesla as the man who invented our future for us. He’s the forgotten genius whose inventions made the modern world. When Musk’s SpaceX rocket shot a Tesla roadster into space on a trajectory that would take it past the orbit of Mars, it was an attempt to become part of the future that Nikola Tesla promised a century ago.

Despite the persistent portrayal of the man as a forgotten visionary, Tesla actually plays quite a big part in modern culture. He’s portrayed as a man ahead of his own time, whose inventions made the modern world. He invented the alternating current system of electrical distribution; he was ahead of Marconi on wireless radio transmission; his plans for the free distribution of electrical power would have transformed the world – if the financiers hadn’t pulled the plug on them.

But much of what we think we know about Tesla is fantasy, and often says more about us than it does about him. Tesla himself certainly did a great deal to promote many of the myths about him that are still prevalent today. But it is worth asking nevertheless why the Tesla myth was so compelling at the end of the nineteenth century – and why it retains so much of its power to fascinate us now.

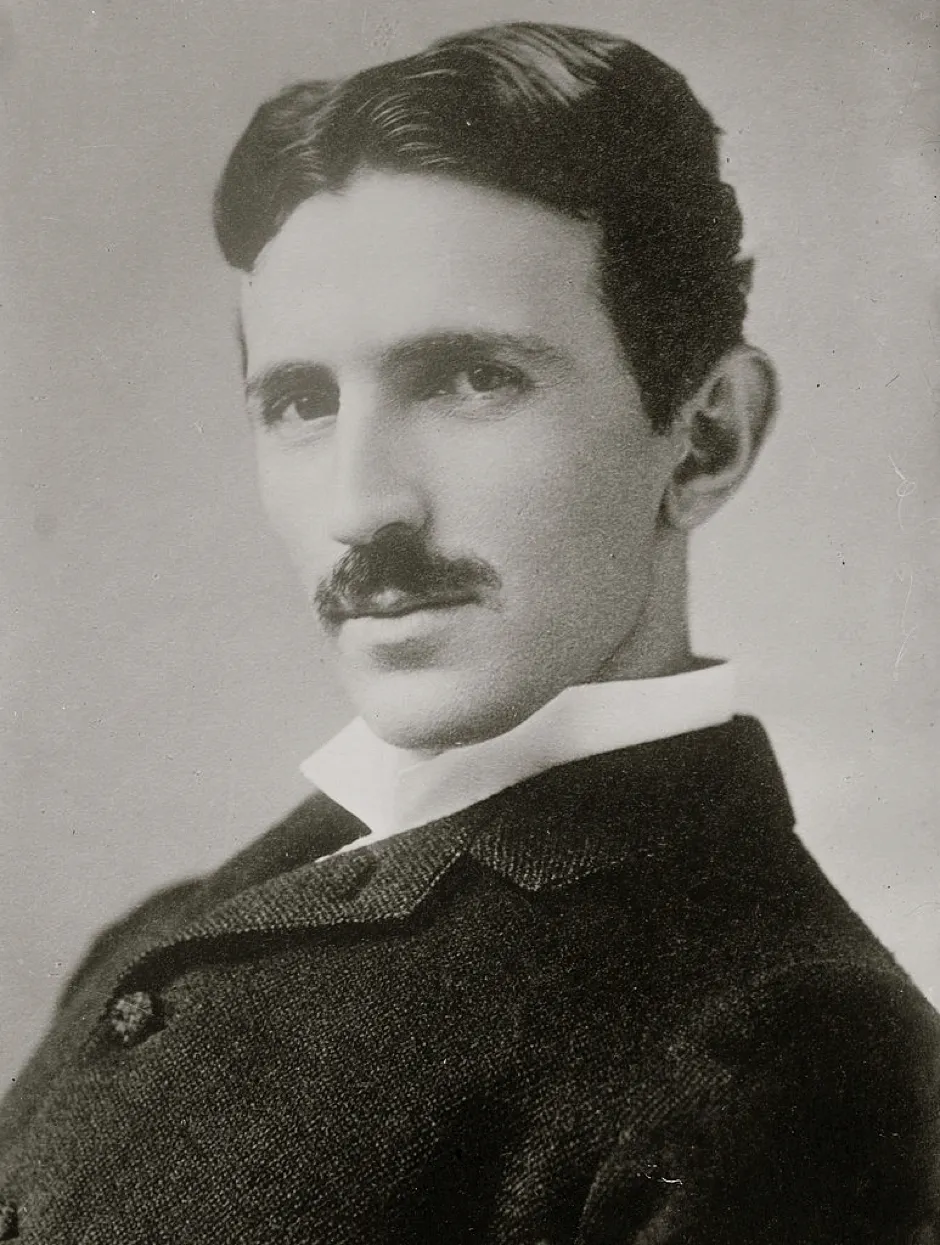

Born at midnight on 9 July 1856 – with a thunderstorm raging, according to family legend – in a little village on the far eastern borders of the Austrian empire, Tesla’s prospects as the inventor of the future might not have looked too promising. But even in the little town of Gospić where he grew up, the tentacles of technological progress were spreading.

Writing his memoirs for Hugo Gernsback’s Electrical Experimenter magazine half a century later, Tesla traced his fascination with invention and things electrical to those formative years. He saw his first electrical experiments at school in Karlovac. Studying at the Polytechnic School in Graz he encountered a Gramme dynamo for the first time and immediately (according to his memoirs, at least) started speculating about how it might be adapted to work with alternating current. Even though he left the Polytechnic before completing his degree, Tesla has acquired a technical education in electrical engineering that made him highly employable in the growing electrical power industries. By 1882 he was in Paris, and working for Thomas Edison.

Read more about great scientists in history:

By the beginning of the 1880s, Edison’s companies were expanding into Europe and looking for young men like Tesla. It was the promise of work for Edison that drew Tesla to America as well, though in the end he was only employed by the Edison Machine Works in New York for a few months before leaving to set up on his own. Tesla’s relationship with Edison is often portrayed as one of intense rivalry.

The reality is that whilst Tesla learned a great deal from Edison about the importance of showmanship and self-promotion for the business of invention, they had relatively little contact once he had left Edison’s employment. They were certainly on opposite side of the hard-fought battle of the systems between promoters of direct current systems like Edison and advocates of alternating current. But that battle was largely over before Tesla became an important figure. Edison’s main rival in that battle was George Westinghouse.

It was only after his lecture to the American Institute of Electrical Engineering in 1888 that Tesla started making a name for himself. There he introduced the alternating current motors he had been working to perfect for several years. His performance was impressive enough for Westinghouse to buy his patents and offer him a job to further improve the motors.

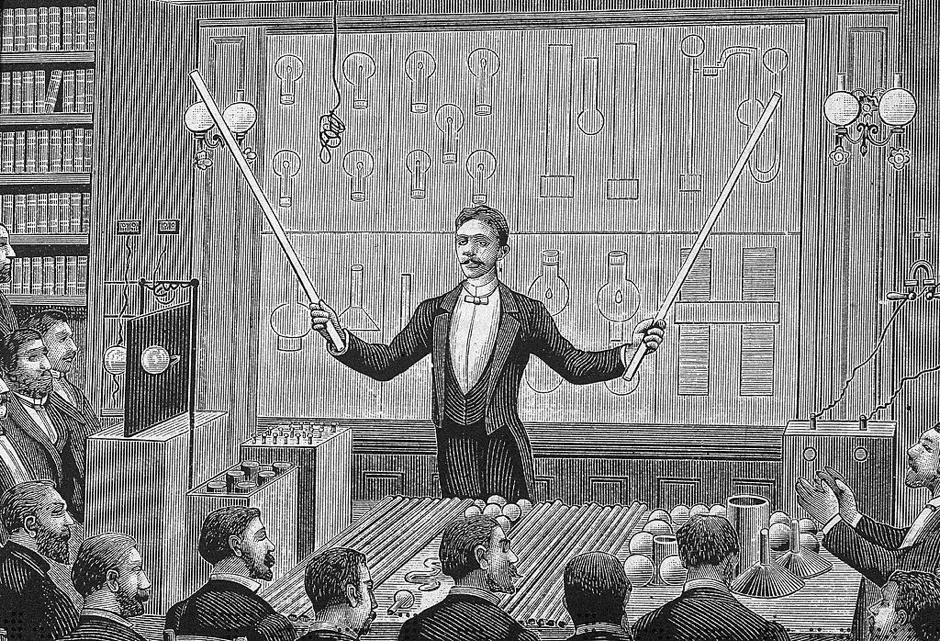

But it was another lecture at Columbia College in New York in 1891, followed by triumphant lectures in London and Paris, that really made Tesla famous. In those lectures he showed off his schemes for wireless illumination, using his newly invented oscillating transformer (the Tesla coil). Reports of the flamboyant performances in which Tesla walked around the stage holding tubes of glowing lights in each hand, captured the popular imagination. They made him into a public figure. Printing stories about Tesla and his inventions was a good way to sell newspapers, and Tesla lapped up the adulation.

The 1890s were the heyday of Tesla’s career. He might not have really had much to do with the ambitious plans to generate hydro-electric power at Niagara falls, but that did not stop the newspapers from making the story all about him. He was the man of the future. When Westinghouse won the contract to supply electricity to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 much was made of the Tesla connection. He even had his own exhibit in the Electrical Building.

When Marconi announced his invention of wireless telegraphy (radio) Tesla told the newspapers that it would never work, and that in any case he could do it all better himself. Tesla in fact had very ambitious plans for the wireless transmission of electrical power. It was to develop those ideas that he built his testing station in Colorado Springs in 1899. He returned to New York at the end of the year convinced that his discoveries there would transform the future.

With $150,000 from the financier J. P. Morgan in the bank, Tesla set out the turn the dreams of Colorado Springs into reality. The result was a laboratory complex built at Wardenclyffe on Long Island, featuring a tower 57 metres in height. The plan was to demonstrate how electric power in huge quantities could be transmitted through the Earth. Locals told the papers about mysterious noises and flashes of lightning generated at the plant.

Read more about great scientists in history:

- James Clerk Maxwell: the most important physicist you probably haven't heard of

- Lise Meitner: the nuclear pioneer who escaped the Nazis

But it soon started to become clear even to Tesla’s most ardent supporters in the press that there was less going on at Wardenclyffe than met the eye. As Tesla’s promises for the future became more extravagant, the clearer it became that they were not being delivered. Wardenclyffe simply fizzled out, in the end, the building repossessed and the tower demolished to pay off Tesla’s debts at the opulent Waldorf Astoria hotel. Tesla spent the rest of his life elaborating on what might have been achieved if only the money to finance his schemes had been forthcoming.

So was Tesla a genius or a charlatan? The answer, of course, is that he was a little of both. His contributions to the development of alternating current technology – and his polyphase motor in particular – were transformative. Many of his more ambitious visions were never realised nevertheless.

But Tesla also understood very well that spectacle, performance, and offering a vision mattered for inventors. In the process, Tesla and his backers in the press helped create a very particular image of the inventor – the flamboyant, otherworldly and decidedly singular saviour of all our tomorrows. It’s the persistence of that image in contemporary culture – the notion that invention is the province of singular and remarkable individuals – that explains Tesla’s continuing attraction. He represents that alluring image of how the future is made.

Nikola Tesla and the Electrical Future by Iwan Rhys Morus (£12.99, Icon Books) is out now.

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard