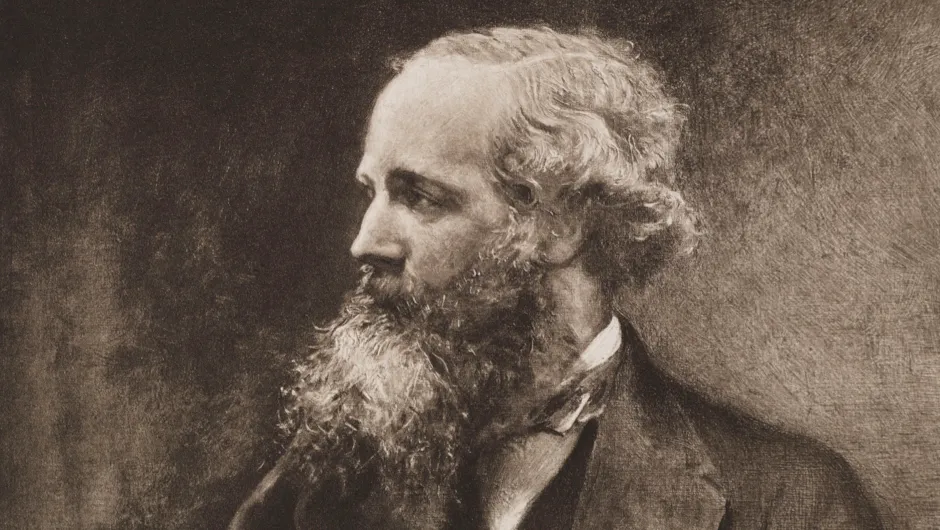

On the walls of his German apartment in 1920s Berlin, and later in his American house in Princeton, Albert Einstein hung portraits of three British natural philosophers: the physicists Isaac Newton, Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell - and no other scientists. Each of this trio he unquestionably revered.

“England has always produced the best physicists,” Einstein said in 1925 to a young Ukrainian-Jewish woman, Esther Salaman, attending his lectures on relativity in Berlin. He advised her to study physics at the University of Cambridge: the home of Newton in the second half of the seventeenth century and later the scientific base of Maxwell, founder of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory in the 1870s.

As Einstein explained to Salaman: “I’m not thinking only of Newton. There would be no modern physics without Maxwell’s electromagnetic equations: I owe more to Maxwell than to anyone.”

Read more about great scientists:

- James Clerk Maxwell: the great scientist with a profound impact on modern physics

- Lise Meitner: the nuclear pioneer who escaped the Nazis

- 10 amazing women in science history you really should know about

In 1931, Einstein expressed this debt in an essay contributed to a Cambridge University Press volume celebrating the centenary of Maxwell’s birth. “Before Maxwell, people conceived of physical reality … as material points, whose changes consist exclusively of motions … After Maxwell, they conceived of physical reality as represented by continuous fields, not mechanically explicable … This change in the conception of reality is the most profound and fruitful one that has come to physics since Newton; but it has at the same time to be admitted that the programme has by no means been completely carried out yet.”

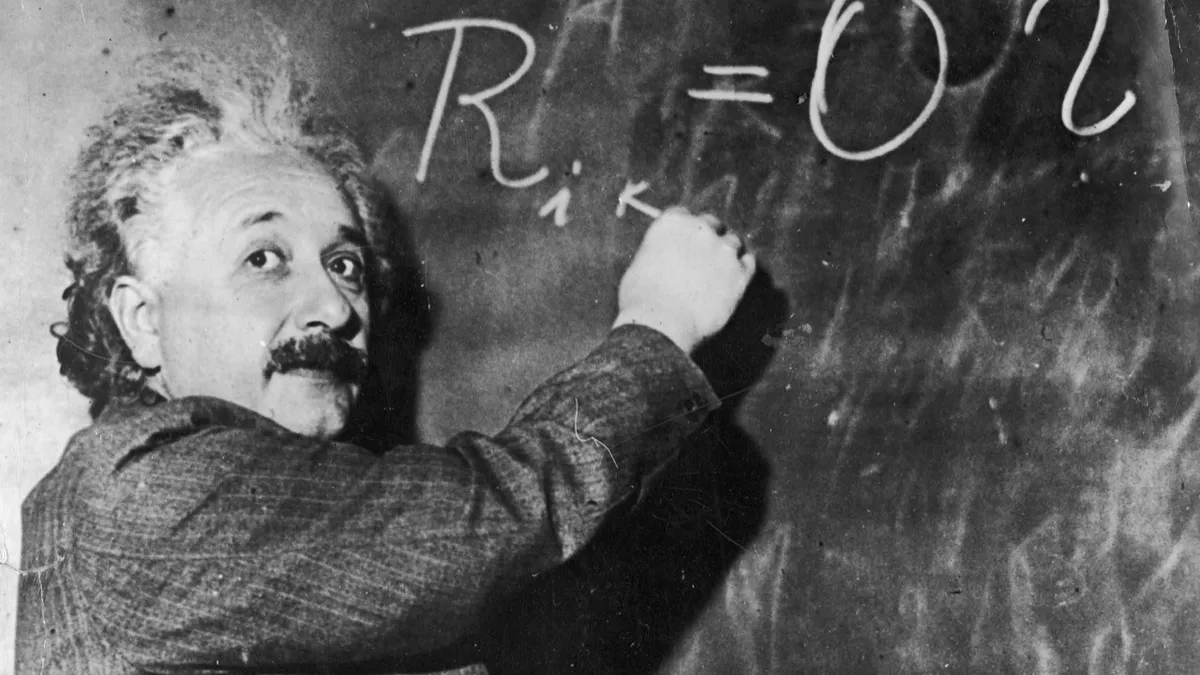

Ironically, Einstein’s British physicist contemporaries post-Maxwell at first rejected his theory of relativity after it was published in 1905 (the Special Theory) and in 1916 (the General Theory). When the Nobel laureate Ernest Rutherford was told in 1910 by the German physicist (and future fellow Nobel laureate) Wilhelm Wien that “No Anglo-Saxon can understand relativity!”, he laughingly replied: “No! They have too much sense.”

According to Masters of Theory: Cambridge and the Rise of Mathematical Physics by historian Andrew Warwick, “In Cambridge during the period 1905 to 1920, Einstein’s work was, by turns, ignored, reinterpreted, rejected, and, finally, accepted and taught to undergraduates.”

Indeed, only one British physicist is known to have corresponded directly with Einstein about relativity up to 1919: G. F. C. Searle, a demonstrator in experimental physics at the Cavendish Laboratory and a regular pre-war visitor to German physicists.

In 1907, Einstein sent Searle a copy of his 1905 paper on special relativity from his position at the Patent Office in Bern. When Searle eventually replied in 1909, after a period of illness, he confessed to Einstein: “I have not been able so far to gain any really clear idea as to the principles involved or as to their meaning and those to whom I have spoken in England about the subject seem to have the same feeling.”

The chief stumbling-block in these British reactions to relativity between 1905 and 1919 was that British physicists, following the discovery of electromagnetic waves by Heinrich Hertz in 1888 and of the electron by J. J. Thomson in 1897, had chosen to adopt an exclusively electronic theory of matter (known as the ETM), accompanied by a firm belief in the existence of the ether: a concept that Einstein and his theory firmly rejected (contra Newton’s theory of gravitation).

In Hertz’s emphatic words: “Take electricity out of the world, and light vanishes; take the luminiferous ether out of the world, and electric and magnetic forces can no longer travel through space.”

What is relativity?

In 1905 Albert Einstein published his first Theory of Relativity, a paper that would change physics forever. The Special Theory of Relativity describes the relationship between space and time and states that the speed of light in a vacuum is independent of the motion of the observer, the laws of physics are the same for all non-accelerating observers.

In 1915 Einstein’s theory of General Relativity expanded on this and outlined how massive objects cause a distortion in space-time which presents itself as gravity.

Discover more about relativity:

Aether and Matter, an influential work published in 1900 by Joseph Larmor, Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge (the chair once held by Newton), argued that matter was electrically constituted and contracted minutely in its direction of motion through the ether according to the relativistic theory of Hendrik Lorentz.

When a student of Larmor, G. H. Livens, published The Theory of Electricity in 1918, he included a short section on “Relativity”, but did not associate the concept especially with the name of Einstein! In fact, Livens opened with the comment that “the whole electrodynamic properties of matter can be explained on the basis of a stationary aether and electrons” - that is, using Larmor’s ETM, not involving relativity.

Only in 1919 were British physicists compelled to accept the truth of Einstein’s relativity and reluctantly abandon the existence of the ether, because of the work of British astronomers, rather than physicists. They were led by Arthur Eddington, a mathematical physicist who had trained at Cambridge but abandoned electronics there in 1906 in favour of astronomy at the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

As a result of observations of a solar eclipse in May 1919 by two British teams located in Brazil and West Africa, it became clear that starlight passing the Sun had been deflected by solar gravity at an angle correctly predicted by Einstein’s theory, not Newton’s theory.

Their conclusion was announced at a historic joint meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society and the Royal Society in London in November 1919, which made Einstein suddenly world famous. In the words of Thomson, the president of the Royal Society - and thus the successor to Newton: “this result is not an isolated one; it is part of a whole continent of scientific ideas… This is the most important result obtained in connection with the theory of gravitation since Newton’s day, and it is fitting that it should be announced at a meeting of the Society so closely connected with him. … If it is sustained that Einstein’s reasoning holds good … then it is the result of one of the highest achievements of human thought.”

Further astronomical evidence collected since 1919 - most recently concerning gravitational waves and black holes - has fully confirmed general relativity.

Einstein on the Run: How Britain Saved the World’s Greatest Scientist by Andrew Robinson is out now (£16.99, Yale University Press)

Follow Science Focus onTwitter,Facebook, Instagramand Flipboard