Beyond the exceptional talents of Marie Curie, Rosalind Franklin and Ada Lovelace, it’d be easy to think that women didn’t used to participate in science. But as science historians Leila McNeill and Anna Reser reveal to Sara Rigby, women have contributed to our understanding of the world, stretching all the way back to antiquity.

Reading about science history, you often get the impression that it was exclusively men doing science for centuries until there were a few superstars, people like Marie Curie or Rosalind Franklin, who broke through. Was that really the case?

Leila McNeill: It certainly isn’t, and we can find women participating in science going back to antiquity all around the world. And one of the problems with looking at figures like Marie Curie and Rosalind Franklin is that they were anomalous in the sense that when they were making their discoveries, it was still very rare for women to be in higher institutions of learning, and scientific institutions in particular.

And so when you’re just trying to look for women in those spaces, those are the figures that tend to pop up. They’re easy to find because institutions keep records and things like that.

One of the things that we were interested in doing was looking beyond those institutions where formal records are kept, to see the different ways that women could have been participating in science on their own terms and in their own way outside of these spaces.

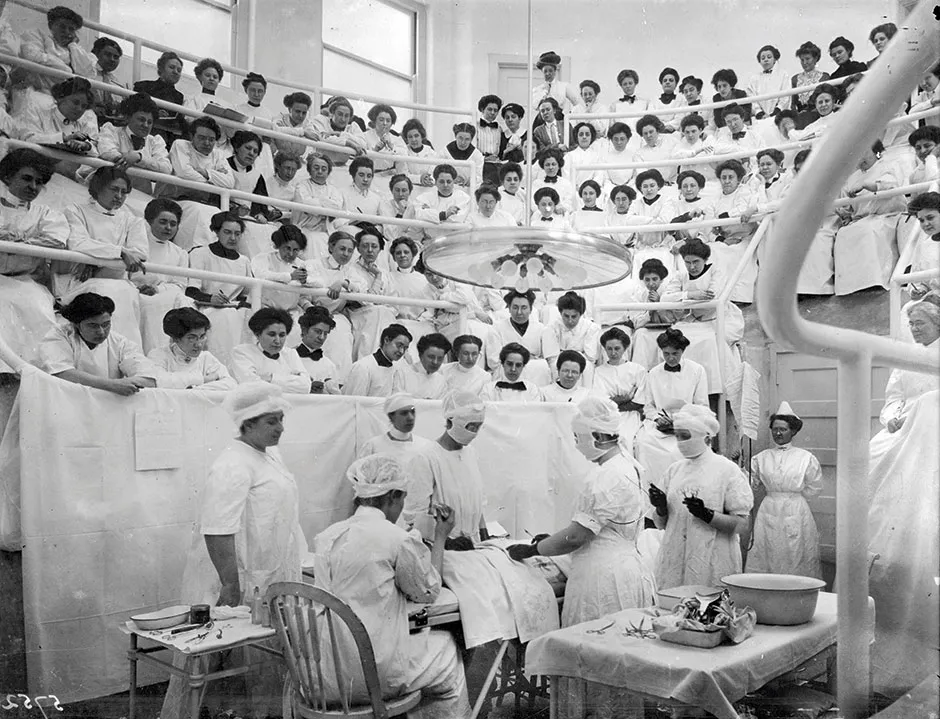

We find women doing this in all kinds of ways, going all the way back to antiquity. And one of the most common ways that we see women participating in medicine is as healers and midwives in various forms. We find that to be the case in antiquity all the way through the Middle Ages, up until the 19th Century when medicine was professionalised.

At that point, it was taken out of the hands of women who were practising these things in their homes and their communities, and taken into that institutionalised setting where, again, that’s where you start getting those unsung women in science, the ones who broke into that institutional barrier.

Read more about women in science history:

- Ladies who launch: the women behind the Apollo Program

- As history proves, women in science need more than just a lab coat

Was there ever a time or place when women didn’t engage in science?

Anna Reser: I don’t think so. I think one of the things that we had to do for this book, and that I think we need to do more broadly when looking at the history of women in science, is to rethink what counts as science.

We use the term ‘pursuing knowledge of nature’ because institutionalised, formalised science didn’t exist until the early-modern period in a way that people recognise. Before that, you’re not really looking for science per se in those terms. But there are people pursuing knowledge about nature, and women can be seen doing that in every period that men were as well.

If we only think about science as something that happens in this broadly public collaborative way across the community of intellectuals, then you’re not really going to find women doing that in a lot of spaces. But if you zoom in a little and look inside homes and communities, women are pursuing this knowledge in these spaces instead.

So instead of looking for women where men are, we look for them where they are. And in those spaces, you do find particularly, like Leila said, women practising medicine to care for their own families and their communities, but also sometimes to make a profession out of it.

They might have been making and selling medicines, travelling around as a healer, things like that – and particularly midwifery and the care of pregnant women and babies.

Why midwives as opposed to doctors? Why was there a gender divide between what sort of medicine people practised?

AR: Well, it’s a little bit complex. A doctor in the sense that we think of it now, like a physician, was not really a profession until the modern period – at least in the sense of having a special, formalised education and all these institutional bodies to which you can belong. The divide, I guess, between midwifery and being a doctor in the ancient world is much fuzzier than that.

LM: One way to think of it is that women cared for women, and that’s more of the divide rather than midwife versus physician.

Were midwives respected in the same way that physicians were?

AR: Yeah, particularly in Ancient Rome. We have a lot of material from Ancient Rome about the profession of midwifery, and one of the things that we have a ton of are relief carvings of midwives at work, which are really cool. They used specialised tools. They had a particular kind of birthing chair that was in their possession; they would take the chair from job to job, helping women to give birth.

And even in the Hippocratic Corpus [a collection of Ancient Greek medical works, which includes texts about ethics, illnesses and diagnostics], there are writings by men that place midwives in this context of professional medical practice. For instance, Soranus [the Greek physician] writes about the characteristics of a good or ideal midwife, so there’s some sort of idea of standard for the profession.

His ideals were that she should be literate and versed in medical theory. Midwives were respected and were thought of as professionals who did a specific job and had specific skills related to that role. And we have lots of evidence of these midwives from that period.

Read more about women in science:

Many women in science history seem to have done a lot of work in astronomy. Yet it often seems to be women who were the wives or sisters of prominent astronomers. Why is that?

AR: I would say that for most of recorded history, that’s the only way that women had to get into those fields. So if we’re talking about someone like Caroline Herschel, her brother William was an astronomer. He needed a housekeeper, so he brought Caroline to England to work in his house, and he just enlisted her to be his assistant, kind of without her permission.

William had his own observatory at their house in Bath. It is very expensive, to buy telescopes and to maintain them. Obviously, the Herschels were an upper-middle-class or upper-class family. They had plenty of family wealth. But that’s not something that the women in the family would have had independent access to. So in order for her to have a space to work in, she worked in William’s observatory.

In order for women to participate in, or at least get close to these formalised and institutionalised spaces for science, usually they would have to do it through a man who was connected to it. Often that would be the husband, or in Caroline’s case, it’s your brother.

How common do you think it was that prominent men in science had a female counterpart who helped them and made their own contributions to the work?

LM: I think it happened a lot more than we have a record of. We’re able to find out about [people like Caroline Herschel] because of what men said about them for the most part. So that, I think, brings into question how many women were doing this work where their husbands didn’t credit them.

It was expected that the women would be the ones helping and the men would be the ones publishing. We do have plenty of evidence that wives and sisters were doing this work, but I think that there was a lot more of it going on than we have a record of.

We’ve talked for the most part about European history. What about outside of Europe?

AR: With the caveat that neither of us are specialists of China, there are a lot of records of women participating in medical practice in Ancient China. A lot of what we know about this comes from things that men wrote about women. And so, again, you do have to filter through these sources and read between the lines.

One of the fascinating things that I found when reading about this is that there are these kind of mythologised figures of ‘grannies’ that are these medical practitioners like herb sellers. The articles by men are cautionary writings about kind of wily women, medical practitioners that you should avoid because they’re tricksters and they will do scams on you and sell you things that don’t work.

But that’s still evidence of women who were medical practitioners: if men were worried enough about them to write them down, they existed. People knew about them. They were figures in public life that you would encounter. And so, you take the stories about these medical grannies with a grain of salt.

LM: This idea of women taking care of women is something that – even if it does seem kind of sexist – was a tradition that allowed women an entry into the modern, institutionalised practice of becoming doctors.

At the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, they accepted students from Japan, from India, from Native American communities. And a lot of them went on and studied women’s medicine, gynaecology and obstetrics – there was a need for that in their communities and in their own countries, since men weren’t doing a great job at taking care of women.

We have this long tradition of women taking care of women, and that became an actual argument for them to become licensed physicians.

Forces of Nature: The Women who Changed Science by Anna Reser and Leila McNeill is out on 20 April 2021 (£20, Frances Lincoln).

- Preorder now from Amazon UK, Waterstones or Bookshop.org